By Chitro Neogy

In 1957, a man born in Amritsar, Punjab at the turn of the 20th century created history by being the first Asian, first Indian American and the first member of a non-Abrahamic faith to be elected to the US House of Representatives. Dr Dilip Singh Saund won as a Democrat in the 29th district of California against Jacqueline Cochran, a popular, celebrated aviator of the times. He was reelected twice as a congressman, before losing his seat primarily for health reasons.

His legacy is both inspirational as well as testimony to the hard work that needs to precede national level political ambitions. Saund drew public support at multiple levels, first through his book “My Mother India”, which demanded an end of British monarchy and drew parallels between racial intolerance in USA to caste discriminations in India, endearing him to the mainstream population. Later he campaigned for naturalization rights for South Asians, leading to the enactment of the Luce-Cellar act allowing immigration quotas for Indians.

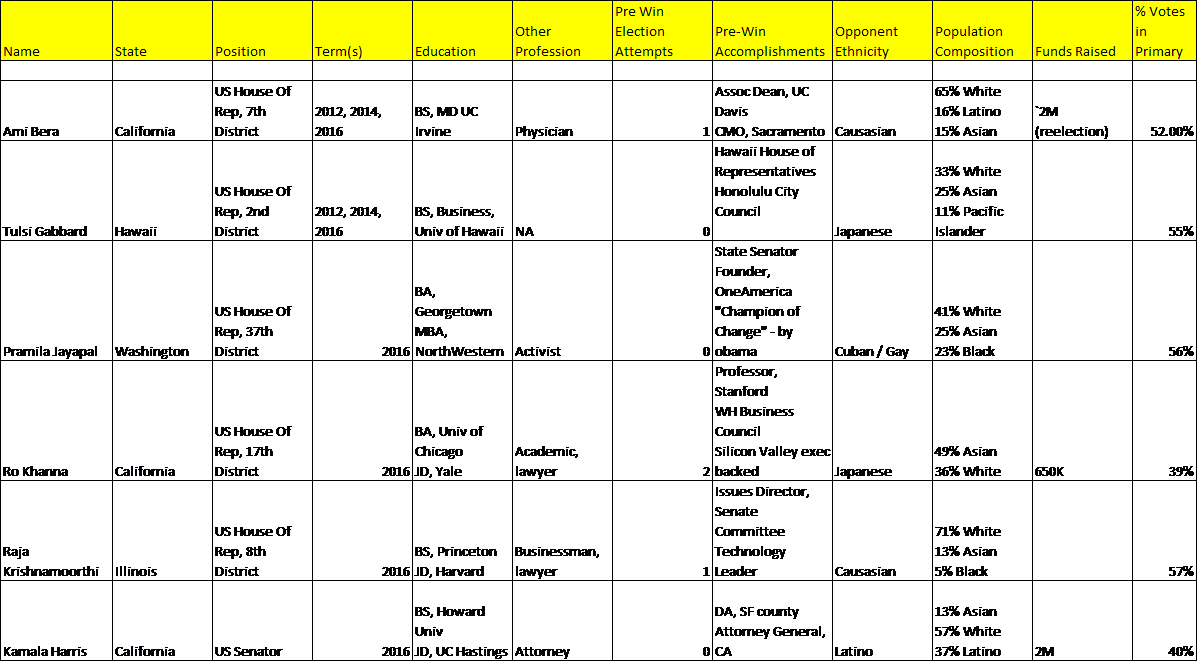

In recent times, several Indian Americans have been elected to the US House of Representatives. A look at their key demographic factors and achievements can be insightful in sighting common themes for South Asian ballot success.

The 2018 congressional primaries in Massachusetts, which featured an Indian American candidate, have fueled much debate in the diaspora on campaigning strategies. In comparison with the data above, a unique challenge in this state is the ethnicity split; 3rd district has 78% White, 3% Black and only 6% Asians. An Indian American politician cannot win solely based on ethnic support. On the flip side, with a large mix of candidates, margins are slim – the Democratic primary winner captured just 21.7% share with a total of 18,527 votes. The same district has upwards of 11,000 Indian American registered voters. Mobilizing this base early is essential for fair returns at the polls. Yet this task is far from easy. First, getting the message out to the Indian voters dispersed across the district is hard for a candidate. Second, Indian Americans in this state are generally averse to voting in non-presidential elections. Many want to know the political manifesto of the candidate and how it relates to them before deciding to cast a vote. Third, unlike in other South Asian nations, Indians still have some challenge of rising beyond provincial borders and viewing a candidate as a representative for the entire community. Finally, adequate fundraising is an inherent necessity of modern day campaigning, and finding political donors in the Indian community, despite their wealth, is tough. The capital gap between the highest fundraising candidate and the Indian American politician in 3rd district was a factor of 10!

The comparative study above also suggests that previous political or social involvement in the state is critical for success in national level politics. The good news is that it’s common for candidates to lose their congressional bid in the initial attempt. They gain a whole new perspective and strategy to refocus on their future campaigns.

Notwithstanding individual campaigning strategies, a systematic process for advancing Indian political candidates is required within the community in Boston. One way to achieve this objective would be to form a PAC that truly represent NRI interests – from immigration, college education, social justice, Indo-US ties among others. Defining goals that resonate with the Indian voters may not be easy – the NRI community is not a political refugee – perhaps an economic refugee, that has done well financially, regardless of the administration in power. The group needs to define a set of outcomes expected from lawmakers aligned with the PAC’s India-friendly vision. Political candidates who subscribe to its goals will receive the support of the PAC, both financially and in campaigns. Far before the 2020 elections, a process for educating the Indian American residents must start, so that they care about voting and understand the distinction between candidates’ principles. Finally, we need to develop a “ready to unleash” digital machinery for rapidly promoting political candidates and their messaging across the state. This endeavor requires developing strong relationships with most South Asian socio-cultural organizations, so that we can rally them for a common cause. Creating this network will greatly alleviate the pains of future Indian American political candidates to connect with their ethnic base.

History has demonstrated that it takes time for political mental models to evolve. African Americans were given voting rights in 1870; Today, just 45 of 535 congressmen are Blacks. Women struggled and earned their franchise privileges in 1920 – a hundred years later, less than 20% women are part of the current Congress. Diversity awareness is creeping into the nation, especially in liberal Massachusetts, despite divisive political stances. A patient yet resolute future holds much promise for South Asian politicians who can successfully connect across their ethnic diaspora, raise adequate funds and propose to fight for solutions that are attractive to the common man.

(Chitro Neogy is a technology manager in a healthcare company. He is also a freelance writer in social and literary publications, as well as the co-founder of the Calcutta Club USA in Boston. The club annually organizes a number of pan-Indian specialty events annually including the largest Indian lit fest in New England, a Culinary contest, an art exhibition and an Indian film festival.

Part of the article reflects views of certain Greater Boston residents including Dinesh Tanna, Prashanth Palakurthi, Gope Gidwani and Praveen Misra.)