BY VIKAS DATTA

Living in a world governed by cause and effect and universal natural principles, most human beings have a propensity to expect the same arrangement in their own lives. But if they want to see correspondence between the natural world and ours, than they have to delve into the atomic and sub-atomic quantum world where the random complexity may upend notions of causation, certainty, and what “reality” is.

Once we realise – and accept – that what we call life is just simply combination of atoms with no special attributes, only matter accomplishing some “extraordinary” things – as the laws of physics dictate, it shows that the numerous ways evolved to explain it – magic, religion, philosophy, and even science – are just human constructs. This brings us to a crucial juncture of thinking about us and the world we are in.

On the other hand, those who don’t, or would not, go into such depths but otherwise find themselves facing the same concerns due to certain actions/reactions and happenings they face in their otherwise untrammelled lives, may come to the same juncture.

This mood of a general despair at a pointless existence or arbitrariness of human principles underpins the concept of nihilism. While it seeks to question one or all the usually accepted aspects of human existence, such as an “objective” truth, morality, values, or meaning, but, across its spectrum, one common thread is that life is without intrinsic value, meaning, or purpose. However, this is not just a pessimistic resignation of the situation, as we will soon see.

While we can seek the trace the origin of this system of thought, finding it has a mythological (Norse) and religious (Buddhist/Jewish/early Christian) pedigree too, it would be more relevant to see what implications this may have for us. And more relevantly, what we can and must do in this situation.

The answers to these can again be found in that high epitome, and boundless repository, of human wisdom – our literary culture.

But first, it must be stressed that endorsement and acceptance of nihilism also varies on a scale. And both ends, there are variants with their own singularities, insofar where one just proffers a diagnosis and the other one is diagnosis – and a prescription, or a prophylaxis, at least.

At one end, there are the inveterate nihilists. The most misunderstood late 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche may be a prime example, once observing: “In some remote corner of the universe, poured out and glittering in innumerable solar systems, there once was a star on which clever animals invented knowledge. That was the highest and most mendacious minute of ‘world history’ – yet only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths, the star grew cold, and the clever animals had to die.”

While modern nihilism is generally – and mistakenly – ascribed to the Russian revolutionary ferment in the mid- and late 19th-century, this strand was a more of an attack by the disillusioned and radicals on the stultifying forms of traditional morality, religion, and society, not a negation, per se, of the whole concepts.

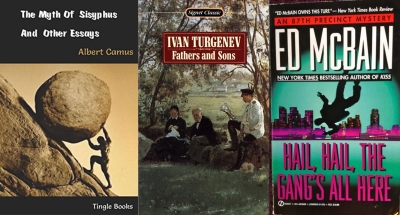

Russian writers of the period like Ivan Turgenev, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Alexander Herzen, and Nikolai Chernyshevsky are, however, unmatched in portraying nihilism in though and action. Turgenev in “Fathers and Sons” also offers a definition (in Chapter 5) too: “…A nihilist is a man who does not bow down before any authority, who does not take any principle on faith, whatever reverence that principle may be enshrined in.”

Examples of extreme nihilism can be found in characters, largely villainous, who stress on how life, the universe, and everything are all meaningless to fight over, how existence is insignificant, and morality illusory. Achilles, from Homer’s Iliad, is one example in one of his rants, and others can be found in the works of H.P. Lovecraft, Ayn Rand, Joseph Conrad (The Professor from “The Secret Agent), George Orwell (the party itself in “1984”, Gordon Comstock in “Keep The Aspidistra Flying”).

However, it is the other end that should be of more interest – and value for us. This may be called “anti-nihilism” but it its proponents are not opposed to nihilism, being nihilists themselves, but of a more realistic and constructive sort.

They are, by no means, under any illusions of the beneficence of their world or society or fellow people, and know how terrible and unfair all these can be, but still, as a conscious choice, choose to be caring, loving, or compassionate. For they do not seek to revel in despair or dissipate their intense cynicism – which remains internal, but arrogate to themselves the right, the power to create meaning, values and purpose in their life.

Hollywood director Stanley Kubrick summed it up well: “The most terrifying fact about the universe is not that it is hostile, but that it is indifferent. But if we can come to terms with this indifference, then our existence as a species can have genuine meaning. However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light.”

Like their polar counterparts, the anti-nihilists also know compassion, love and empathy are only fictional, but the difference is that for them, these are fictions still worth believing in, and acting on.

Most conscientious doctors. private detectives (Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, in line with the author’s “Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean…” sentiment), police officers (say Martin Beck and his friends in Per Wahloo and Maj Sjowall’s pioneering Nordic crime fiction series, Steve Carella, Mayer Mayer, and others of Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct), and even superheroes, are the best example of these tropes in fiction.

Take Batman. Despite the version you pick, the young Bruce Wayne, having undergone a seemingly random and meaningless tragedy that left him an orphan, could have decided that life itself was meaningless and turned to depression. Instead, he chose to focus on what his parents meant to him and to his home city Gotham, re-inventing himself as a champion of order and justice, against the mayhem and chaos caused by the Joker, the Penguin, and the like.

Sir Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books feature quite a few proponents as principal protagonists, especially Death, represented as an anthropomorphic personification, and is wise too (“You need to believe in things that aren’t true; how else can they become?”), and City Watch commander Sam Vimes.

But the best example is Lord Vetinari, the city’s competent and benevolent ruler, who repeatedly mocks the inherent evil/stupidity of people, but perseveres on for them regardless. He once also goes on to give a graphic example of the indifferent cruelty of nature he observed, and concludes it taught him that if there was a supreme creator, it was the duty of every sentient being to become a moral superior.

Then, recent example is Richard Powers’ 2018-Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “Overstory”, on trees and humanity’s relation to – and destruction of – the environment, has among its nine main characters a Nietzsche adherent, who goes on and on about the pointlessness of human endeavors, yet is most idealistic and determined to do good.

While Albert Camus’ “The Stranger” has the protagonist Mersault as an example, though a most unprepossessing one, his exposition is his four-part essay “The Myth of Sisyphus” (1942, English translation 1955) is more germane.

Here this engaging philosopher introduces his theory of absurdism, or the link between the human desire to seek meaning in life and the studded silence of the universe in response, and firmly rules out suicide (including philosophical in taking recourse to religion), in favour of embracing the absurdity of our life as freedom.

Camus uses the mythological villainous Greek king, condemned to ceaselessly roll uphill a heavy boulder – which rolled back to the base as soon he reached the summit – to show why we must keep doing what we have to do without thinking it futile.

“…The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy,” he ends. (IANS)