VIKAS DATTA

Seeking some informed opinion on some aspect of human society, culture, or politics, that is not rooted in received or polarised social media ‘wisdom’, but not too keen on ploughing through a dense tome? Try a range of public intellectuals, usually academics, who weigh in on such matters, but in a simple and terse form — like Italian scholar Umberto Eco.

In this particular form, you don’t need to read his entire book — and even if you do, it will offer an expansive buffet of ideas and thoughts, rather than a single interminable meal centred on one theme.

Human ingenuity shows itself at its best in constructing forms of expression for communication, edification, or entertainment, it is even better at progressively curtailing their span, as down the ages, or even mere generations, attention spans shorten or there are other calls on people’s time.

In written forms, sagas evolved into novels and novels into short stories, epics into poetry, letters into e-mails and then into SMSes/chats, and in the audio-visual realm, films into serials and even into “reels” or other forms of short videos, and so on.

As far as the written word is concerned, even non-fiction — especially the one with insights into various facets of the human condition, but usually in rather bulky volumes and/or containing some impenetrable language or an entirely new vocabulary, does not escape this process.

This form is much shorter, (usually) more informal but no less focused — it is the essay and we must thank a 16th-century French nobleman for developing it.

Michel de Montaigne termed his attempts to put his thoughts into writing as “essays” (from the French infinitive “essayer”, or to try) and his 107-strong oeuvre, containing pieces like “Fortune is Often Observed to Act by the Rule of Reason” to “That Our Desires are Augmented by Difficulty” to “Of Managing the Will”, is a delight to read — and still relevant.

The essay, as per English philosopher and author Aldous Huxley, is “a literary device for saying almost everything about almost anything”, and “by tradition, almost by definition, the essay is a short piece”.

And “true” essays — unlike John Locke’s “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding”, which clocks in at nearly 600 pages, are not meant to be lengthy — usually a single-digit or low two digits, and rarely extending into three digits.

Many renowned authors — from Albert Camus? (“The Myth of Sisyphus”) to Joseph Conrad?, from Sigmund Freud? to George Orwell?, and from Mark Twain? to J.R.R. Tolkien — have used the form to espouse a range of issues, from the personal to the factual, to the abstract.

In more recent times, there have been Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, Amartya Sen, and many more (depending on your political inclinations).

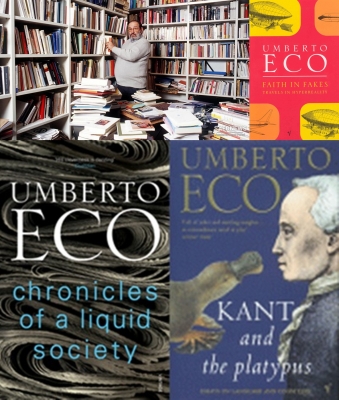

But it is Eco (1932-2016), an academic with significant contributions to semiotics, or the study of human signs and symbols and their interpretation, aesthetics, literary theory, media culture, and philosophy, who is the focus here.

He came into the limelight with his debut novel “The Name of the Rose” (1980, English 1983, film starring Sean Connery and Christian Slater, 1986), which features the rational, tolerant, and mystery-solving monk William of Baskerville, whose name links a celebrated medieval philosopher who invented a tool to cut unnecessary speculation and the area of a famous detective’s most celebrated exploit.

Eco went on to achieve more fame with further six novels, including “Foucault’s Pendulum” (1989), “The Island of the Day Before” (1995), and “Numero Uno” (2015), where he dealt, usually satirically, with topics like conspiracy theories, the occult, the transience of memory, the tabloid press, etc. His non-fictional writings are no less engrossing.

There are over 40 of his non-fiction works. Some are academic works, many others are anthologies of his newspaper articles, speeches and conference papers, all offering perceptive, trenchant, even opinionated, sometimes ironic and satirical, but always articulate, arguments on topics ranging from translation to imaginary lands and beasts, Superman to the effects of tight jeans, and from populist politics to cultural and technological regression.

Let us look at some of these — quite cursorily, with mere hints of what they contain to whet appetites, for too much description would spoil the intending reader’s experience.

“Faith in Fakes: Travels in Hyperreality” (1986) begins with a mildly polemical but cogent argument on why Eco and other European academics, unlike their American counterparts, feel the need to express their views on a whole range of issues, spanning politics, culture and even sports, and then what significance Eco’s subject — semiotics — can have in daily life.

The high points are the perceptions of the Middle Ages, the secret meaning of spectator sports, and a dissection of the Hollywood classic “Casablanca” through the archetypes its characters, settings, and situations represent.

“Serendipities: Language and Lunacy” (1998) is another witty inspection into how myths, and plainly loony ideas, can drive historical developments and have unintended consequences, such as the discovery of America, the quest for a perfect language, and other such esoteric subjects.

“Kant and the Platypus: Essays on Language and Cognition” (1999) is a deep dive into what its sub-title promises — comparison of linguistic and perceptual meaning when confronted with the unencountered, or different ordering of knowledge as represented by a dictionary and an encyclopedia.

Eco reportedly warned fans of his fiction that this one is “not a page-turner”. He said: “You have to stay on every page for two weeks with your pencil. In other words, don’t buy it if you are not Einstein.”

“How to Travel with a Salmon & Other Essays” (1998), as the name promises, is full of advice for dealing with or identifying all sorts of incongruous situations, including becoming a TV host; differentiating between a movie with strong sexual content and pure pornography; and choosing between spending your vacation with an 80-year-old leper or Demi Moore (well, it is of the 1990s, after all).

“Mouse or Rat?: Translation As Negotiation” (2003) is geared towards language buffs as it shows how the issue of translation can create cultural problems, but it is “Turning Back the Clock: Hot Wars and Media Populism” (2007) that will appeal to a wider section.

The main focus is on how 9/11 and all the changes it brought about represented a retrograde development in the march of human progress that was being celebrated since the end of the Cold War, and how a number of pernicious ideologies — anti-science, religious fundamentalism, xenophobia, and the like — resurfaced, and still persist. The write-ups on political correctness and the rhetoric of oppression are also riveting.

“Inventing the Enemy: Essays on Everything” (2012) has its title piece stemming from an encounter with a Pakistani taxi-driver in New York to dwell upon why humans need to create a focus for hate — delivered in Eco’s usual iconoclastic manner. The utopia/dystopia that ensues when proverbs are taken literally is another highlight.

Finally, the posthumously published “Chronicles of a Liquid Society” (2017) has a range of trenchant insights, including into the cell phone culture, the internet society, racism, books — including if adults should fear Harry Potter, and why we read mysteries, individualism (is too much bad?), the absence of values, and much more.

It is common to mock intellectuals — or in these times, denigrate them. Reading Eco shows why we need them, to save us from the follies we are all too prone to enmesh ourselves in. (IANS)