New Delhi– A month after they returned from Tokyo, Saikhom Mirabai Chanu and Vijay Sharma are back at the gymnasium in Patiala’s National Institute of Sports. Chanu, 27, is swinging a kettlebell up and down, then from left to right, as Sharma monitors. For the sports star-coach duo, this is their natural habitat, one where they feel at peace. The last 30 days have been unlike any Chanu has ever experienced in her life. The weightlifter, who won silver in the 49kg category at the Tokyo Olympics, has had to swap her usual eat-train-sleep-repeat routine for a packed event-interview-shoot-repeat schedule. In this time, Chanu has met countless ministers, sports stars, film stars and several other important people. Everywhere she goes–a photoshoot, a television studio, a felicitation function–they want a selfie, they want to get as close as possible to her medal, perhaps even touch it. And they always order her a pizza.

Little Miss Sunshine

“I know all these — meetings, functions — is important too. All these people wanted me to do well and cheered me on to win a medal.” And so, Chanu obliges all their requests, always with a smile that lights up a room. The high-watt smile did not leave her face on July 24 at the Tokyo International Forum, even when she couldn’t complete her final lift. She had done enough — a previous clean lift of 115kg, and 87kg in the snatch before that, adding up to a total of 202kg had won her the silver — and redemption. “I almost forgot where I was standing,” she recollects with a laugh. “Then the announcer took my name and I realised, ‘Oh, this is the Olympic podium!'” In an arena sans spectators and on a podium where masked victors girdled medals around their own necks, Chanu’s silver opened India’s account in Tokyo on the very first day of the Games.

Mind Games

Chanu has what you would call a sunny disposition. And it inevitably shielded her arduous journey to Olympic silver. Five years ago, competing at her first Olympics in Rio, Chanu had crashed out of the competition after failing to register even one lift in the clean and jerk section of the event. It crushed her confidence, and the then 21-year-old cried all the way from the arena to her room in the Olympic Village, slipping into a protracted depressive episode in the months to come. “I still don’t know what happened to me that day,” she says. “It felt like I had forgotten what to do.” Back in India, she was ready to give up weightlifting altogether, as she felt she had let everybody down.

“Everyone told me I was young, and it was not the end of the world — my mother and my coach especially. But it was very tough for me to get out of that zone. It was a combination of disappointment, anger and losing all hope.” Her supportive family’s secure environment and a series of counselling sessions helped her regain her confidence and self-belief.

Winning Streak

In 2018, she became the Commonwealth Games champion but had to pull out of the Asian Games and World Championships due to a lower back injury. The same injury flared up in 2020, worsening her back and confining her to her room in Patiala (she was training there for the Olympics at the National Institute of Sports) for almost two months during the nationwide lockdown.

By the time restrictions had been partially lifted and training resumed, there was plenty to worry about. “I’d been lifting heavy for so many years, but it never hurt so much,” she recalls. Around this time, the postponed dates for the Tokyo Olympics were also announced. “My shoulders and back were so stiff that I needed a full day’s rest after one session, which wasn’t normal.” It took a trip to St. Louis, USA, to get her condition diagnosed by lifter-turned-physiotherapist Aaron Horschig. Once the biomechanical flaws in her technique were identified, it didn’t take long for the irrepressible athlete to resume training without any major discomfort. “My competition was against myself and my own body at that time,” she sagely admits.

Olympic medal in the bag, Chanu now has her eyes set on next year’s Commonwealth Games and Asian Games. She signs off with a message that is likely to inspire many girls in India: “Weightlifting is not dangerous for girls, it is completely safe. Look at me. If I can do it, all of you can.”

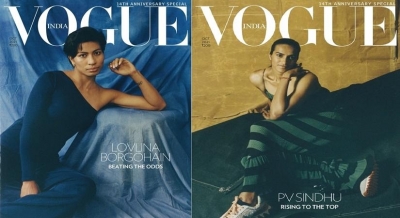

PV Sindhu

India’s most marketable female athlete, the Hyderabad-based badminton star opens up about expectations and the pressures of fame. Since her return from the Tokyo Olympics, PV Sindhu has been clocking miles faster than some of her on-court smashes tend to be. It’s been just over two months since the event ended and the badminton player has already been to Hyderabad (where she lives), Lucknow, Vijayawada, Visakhapatnam, Mumbai, Tirupati and Delhi, where she had ice-cream with the Prime Minister. It is part of an enduring celebration to mark an achievement that’s rare in India — an Olympic medal.

Rare Form

India’s most marketable female athlete and among the world’s highest-earning sportswomen, Sindhu’s understated middle-class values root her strongly to reality and help manage unrealistic expectations from fans and the fraternity. Her parents Vijaya and Ramana played volleyball competitively, but as fate would have it, the younger of their two daughters trotted into an adjoining badminton court at age seven.

That triggered a lasting relationship with the sport, inculcating in Sindhu a heady mix of skills, technique, speed, agility and the stamina to succeed. Coach Pullela

Gopichand moulded her talent into adulthood, guiding her to second place in Rio and her highest ranking of world number 2 in 2017. Since then, Sindhu has worked on her technique, with help over the last year and more from coach Park Tae-sang.

The pandemic, in a way, helped after she secured permission to practise at the Gachibowli stadium, which allowed her the ‘feel’ of a large arena. Unlike ‘normal’ times, international players could not gauge their opponents in the badminton circuit because there have been few tournaments since March 2020. “Due to the pandemic, we didn’t know how the [other] athlete was doing. That was different in Tokyo — everyone had different techniques and we had to be prepared for anything,” says the 26-year-old who has her sights set on Paris 2024.

Under Pressure

The cross-country travel Sindhu has done so far is not new to her. Rio changed her life most significantly-personally and professionally, buoying her with fame and burdening her with expectations. The silver medal, which made her the first Indian badminton player to bring one home, elevated her stardom. She returned to be feted with a parade, riding atop an open double-decker bus in Hyderabad.

“You see your name on billboards and children hold your posters…It was a different thing altogether. Five years later, getting a medal in Tokyo is another big thing. It’s not easy.” “It’s not easy at all,” she repeats. “There has been pressure. Tokyo was harder than Rio because the responsibility has been a lot more.” Everyone says, “‘We need a medal from Sindhu’. Rio was my first time, so I was the underdog,” says Sindhu, who later clinched a gold at the BWF World Championships in 2019 that added further lustre to her glowing resume. Sindhu is aware of the negative impact of fame and expectations on sportspeople, aspects most recently highlighted by tennis player Naomi Osaka and gymnast Simone Biles. It’s not easy to do it day in and out-train, travel, compete, ride the graph of successes and disappointments. “The scrutiny will be there and people will talk and watch out for you. When you are young, you think you want to be in the limelight and want to be number one. When you get there, you have to enjoy it. You don’t have to complain about it. Enjoy how it comes and let go of what is not needed,” she advises. In the last year and a half, meditating has helped her stay calm. “There will be pressure at times and I think it’s okay… You should not think about what people want. Think about what you want and be focused. If you win, it’s good for you and for people out there,” says Sindhu, who has a measured, careful manner of speaking.

This month, Sindhu will be back on the circuit with the Denmark Open and French Open. “Winning and losing is part of life,” she says. “At the end of the day, it depends on the individual. I choose to answer with the racquet.”

Lovlina Borgohain

At the end of the day that saw Lovlina Borgohain lose the semi-finals to world number 1 and eventual gold medallist Busenaz Surmeneli of Turkey, the Indian boxer wrote a heartfelt entry in her diary that read:

“Mera aim toh pura nahi hua…par mera itna achcha preparation nahi tha…mera gold ke bare mein sochna hi galat tha. Jis tarah se maine train kiya, jo injury [Lisfranc foot injury] mujhe hui, main Olympics khel payi, yehi bahut badi baat hai.”

A day earlier, the 23-year-old Assamese sports star beat World number.2 Taiwanese middleweight boxer Chen Nien-chin in the quarters to become the third Indian boxer-and the first from her state-to win an Olympic medal (bronze in the women’s welterweight category: 69kg). It finally felt real, the dream Borgohain had nurtured since childhood.

Hard Times

Growing up, Borgohain remembers watching her parents worry about putting the next meal on the table. Despite financial hardships, what upset her mother most was being pitied by village folks for having three girls. It only fuelled a young Borgohain’s ambition to achieve something, for her mother’s sake. “I’ve never screamed so loudly after winning any match. But after I ensured the medal for India, I let go of all the pent-up emotions of all these years. Even if I lost any competition, I’d remind myself that the Olympics is where I’d perform-and to be able to have done that took all my stress away,” says Borgohain, a two-time World Championships bronze medal winner.

No Fear

Despite many obstacles, Borgohain, who admits she isn’t the most fearless boxer around, entered Tokyo oozing confidence, bolstered by the hope that a billion Indians were praying for her success. However, she felt nervous in her first match and wasn’t able to play the way she wanted to. The pressure of the opening round over, Borgohain was next up against Chen, an opponent she’d never managed to beat in four attempts.

So how did she eventually turn things around in her favour? “I didn’t speak to the coach or discuss any strategy this time. Every coach has their own way of looking at things, and after every loss, they would suggest different ways to beat her. It didn’t work, though. I kept losing to her. This time, I just wanted to play as I saw it. I came up with my own strategy-and it worked. There was no fear this time. I told myself that I’ve played with fear all my life, but today, I will just play freely.” Another interesting departure from her routine was giving up meditation in the run-up to Tokyo. It was her debut Olympics, but Borgohain felt that calming her mind wasn’t working for her. “I didn’t want to do any controlling exercises for the mind. I just wanted to set it free.”

Girl Power

Currently, while she’s making the most of her time with family, indulging in her mum’s signature Assamese pork dishes, Borgohain intends to begin training for Paris 2024 soon. “Mujhe Paris mein apna dream pura karna hai, gold laana hai,” says the fervent pugilist, who got to know about boxing for the first time when her father showed her a newspaper clipping of Muhammad Ali. “My father told me how great a boxer he must be that we are reading about him in our tiny village. That day I thought it would be nice to take up boxing and achieve something too.” And on that front, Borgohain is well on her way. (IANS)