BY VIKAS DATTA

Humans, possibly following some atavistic but ingrained impulse, are initially geared up to recognise a binary value system, but most soon learn that our world, and its people, are too complex to be slotted into just two options.

This, and the realisation that not everyone obeys the rules, to their obvious benefit, leads to appreciation for the anti-hero, or protagonists with their own value systems.

That may help to explain why we have a sneaking admiration — or interest, at least — in fictional characters whose “heroic” credentials are quite vague as to morality, say James Bond, or his equally lethal but less glamorous American counterpart, Donald Hamilton’s Matt Helm.

Or for that matter, those compelled to take the law into their own hands, vigilante style — an entire host, spanning various genres and media, from Don Pendleton’s Mack Bolan, alias the Executioner, to V from “V for Vendetta”, to Paul Kersey (Charles Bronson) in the “Death Wish” series of films, to Bollywood’s Angry Young Man.

Then, there are those on the other “wrong side” of the law — ‘Godfathers’ Vito and Michael Corleone or other Mafia figures and a number of similar outlaws, desperados and dacoits whose exploits fail to evoke the sort of moral outrage they should be expected to.

In the grey area between these realms too are “heroes” doing “criminal” acts, spanning from conmen to assassins for hire.

Let us take up the latter. They are not just psychopaths, and not that uncommon, for governments around the world pluck a considerable number of men — and women — from normal life, train and encourage them to kill, use them in conflicts — and eventually release them back into mainstream society.

Most of them do adjust to a more peaceful millieu, a few need to find an outlet for the violence they are still capable of or can be provoked too, especially when the world — and the people — they hope to return to have changed.

Like Max Allan Collins’ ‘Quarry’ — the first and most famous series of this prodigious and prolific writer across all forms — novels, screenplays, comic books, comic strips (Dick Tracy), movie novelisations (“Saving Private Ryan”, “Waterworld”, among others), and historical fiction.

Collins’ oeuvre comprises over a dozen series, including the intricately researched and plotted Nathan Heller series (20-odd installments and still going strong) about a Chicago policeman-turned-private investigator who gets drawn into famous unsolved/controversial US crimes from the 1930s to the 1960s — from the disappearance of female aviator Amelia Earhart to the JFK assassination plot — and sometimes, takes an active hand.

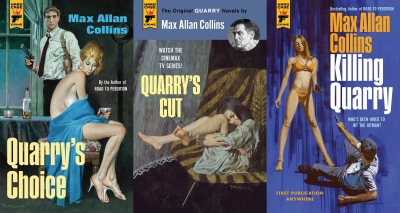

But it is the Quarry series about a former US Marine sniper-turned-professional assassin that is the most rivetting, and even inspired a short-lived Cinemax TV show in 2016.

About Quarry, Collins later said that his aim, apart from proving that “crime fiction could be written using a common Midwestern US small-town setting rather than the much more common New York or Los Angeles”, was to create a higher level of anti-hero — having already done so with his Nolan series about a professional thief — by making the character a hired killer, but otherwise “a normal person in his early twenties — not a child of poverty or cursed by a criminal background, but a war-damaged Vietnam veteran”. This was also aided by the narration being first person — to show us his thinking and mental make-up.

Our hero — we never learn his real name — returns home from the Vietnam War to find his wife cheating on him. Resolving to leave her, he first wants to find out his rival’s intentions, but ends up killing him. He is arrested but the charges against him are dropped. Cut off from his family and virtually unemployable, he is then approached by a mysterious figure, only depicted as the “Broker”, who offers him a job as a contract killer.

When he agrees, the Broker, who is fond of renaming his operatives, calls him Quarry, for being a “hollowed-out stone” — as we learn. We also find out that the Broker’s process comprises setting up two-member teams, in which the “Passive” member, responsible for reconnaissance and if needed, back-up, carries out detailed surveillance of the target up to a month before, and the “Active” member, responsible for the killing, comes in two-three days before carrying out the hit.

It was supposed to be a one-off with “The Broker” (1976; reissued as “Quarry”, 2015), which Collins began to write in 1971 when at the Writers Workshop at the University of Iowa, but only found a publisher in 1975.

It recounts how Quarry, in his fifth year of working for the Broker, realises the mission he is on is a huge double-cross and takes matters into his own hand — leading to a showdown on a deserted road, which leaves him independent.

“The Broker’s Wife” (1976; reissued as “Quarry’s List”, 2015), shows him get into a different role. Quarry finds the secret papers of the Broker, with details of all his colleagues, and the real nature of the business he had been involved in. Now he tracks down the other killers working for his former boss, ascertains their targets, whom he approaches and warns of the threat to their lives.

If they believe him, then, for a fee, he offers to eliminate the assassin concerned. For some more money, he will identify the person conspiring to get them killed, and take them out too.

This goes on in “The Dealer” (1976; reissued as “Quarry’s Deal” 2016), where the other assassin is a beguiling woman, and in “The Slasher” (1977, as “Quarry’s Cut”, 2016), where Quarry comes across another of his ex-colleagues in his neighbourhood and the trail leads him to a pornographic film set, where suddenly dead bodies start piling up at the isolated house where the shooting is taking place.

After a short break, he came back in “Primary Target” (1987; “Quarry’s Vote” 2016), where he is approached by a client for a political assassination but declines — to his own cost. His rampage of revenge follows.

Quarry returned nearly two decades later in “The Last Quarry” (2006) about what was supposed to be his last case — with an explosive finale.

The character, however, seemed to be too hard for Collins to let go of, so he started to fill up gaps in his career.

Our hero returned in “The First Quarry” (2008), detailing his first operation for the Broker, and from then, the chronology gets a bit muddled.

“Quarry In The Middle” (2009), set in a casino town; “Quarry’s Ex” (2010), where he runs into his ex-wife at a film shoot; “The Wrong Quarry” (2014), which is quite chilling once you learn who the real villains are; and “Killing Quarry” (2019), where he is saved from death by a beguiling counterpart from his past, are all set in his present period as a counter-assassin.

On the other hand, detailing his period as the Brooker’s tool are “Quarry’s Choice” (2015), which takes off after an assassination bid on the Broker; “Quarry In The Black” (2016), where he is tasked with eliminating a charismatic Black politician (but takes matters into his own hands); and “Quarry’s Climax” (2017), where he has to save the publisher of a pornographic magazine from other assassins.

“Quarry’s Blood” (2022) is purported to be the final act.

Though full of violence (but never gratuitous) and sex (not that graphic), tight plots, and masterful dialogue, the series is made more unforgettable by the main character himself.

He may be a killer but not a psychopath, insightful enough to know when something is wrong in the story he has been told. He also has acuity and a moral compass strong enough to set matters right. The evocation of the 1970s world — which may seem the distant past — is an added bonus, and so are the moral issues. (IANS)