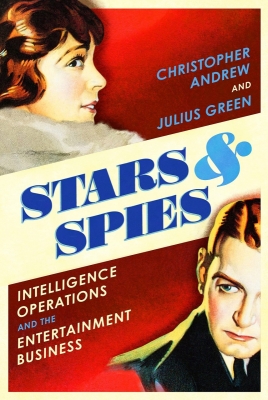

Title: Star and Spies: Intelligence Operations and the Entertainment Business

Author(s): Christopher Andrew and Julius Green

Publisher: Bodley Head/Vintage (PRH)

Pages: 496; Rs 899

One is concerned with protecting the state and obsessively operates in secrecy, and the other to interest and amuse the people in their leisure time and proactively courts publicity. There may seem nothing more widely divergent than the realms of espionage and entertainment. But are they?

An intelligence official is helped to escape his occupied country by a glamorous actress who passes him off as her secretary, a future Bond film producer joins an Oscar-nominated scriptwriter in an influence operation that takes in a US President, one of the most famous double spies is named after one of the most popular — and enigmatic — actresses ever, a key source in a political scandal is named after a contemporary pornographic film, and an audacious cross-continental rescue operation is mounted as a film shoot.

These — and more — examples show that despite their perceived differences, spying and showbiz can, and did, have a close relationship, as intelligence historian Christopher Andrew and entertainment historian Julius Green contend, and go on to demonstrate in the riveting ‘Star & Spies: Intelligence Operations and the Entertainment Business’.

Noting that the “interplay between the worlds of espionage and entertainment goes back at least 2,500 years,” they say that as proponents of one skulk in the shadows and of the other, bask in the spotlight, the two fields may seem widely separated for a “famous entertainer is generally a successful entertainer, while a famous spy is most often a failed spy or an ex-spy,” but “both professions, however, often require similar skills and sometimes attract similar personalities.”

What these skills are and how do these affinities overlap is what the authors go on to show in this meticulously researched and intricately written account, spanning the reign of England’s Elizabeth the First in the late 16th century, which is seen as a golden period of theatre, to Elizabeth the Second in the late 21st, where the boundaries of entertainment have widely expanded, via a broad range of wars, revolutions and other forms of conflicts in the intervening centuries.

They also stress how espionage and covert operations are not only concerned with stealing secrets, but also to advance a state’s interests by creating a narrative and widening its influence, and in some cases, crafting deception operations to mask intent and planning.

The realm of entertainment, which owes its success to creating a paradoxical realistic make-believe world, seems well-suited to all these pursuits — and has contributed to these ends of state policy.

Then, given the perception that spies or other agents are supposed to operate secretly and avoid drawing attention, would a flamboyant entertainer or cultural figure be able to accomplish the same end, using their visibility as a cover?

If any of them is used, consciously or unconsciously, by one side, with the thought in mind that the other side would think their opponents probably wouldn’t do something so obvious, but not be certain if it is being attempted and counting on them (the second side) to think so. Confusing?

Welcome to the “wilderness of mirrors” that effective, but devious, intelligence operations are about. There are some examples here.

While the focus is much more on the western world and its cultural manifestations, as well as the KGB and its predecessors and successors, the authors do cite the contributions of the profound ideologues of the ancient Indian and Chinese civilisations — Chanakya and Sun-Tzu — on the need for intelligence and the role that entertainers can play in this regard. Chankya, in fact, is credited with the evolution of the ‘honey trap’ method.

The authors also incorporate a range of contemporary Bollywood films dealing with intelligence operations (though they do miss out on one of the earliest works — Chetan Anand’s ‘Hindustan Ki Kasam’ (1973). Some Chinese espionage novels and mass media representations also figure.

Encompassing a range of literary figures, from Christopher Marlowe to John Le Carre, and enduring creations from Prospero (in Shakespeare’s ‘The Tempest’) to James Bond (and how real-life spies view their famous fictional counterparts), the book is not just about the espionage forays of creative practitioners and entertainment industry luminaries, but about how the entire spectrum of cultural creativity can be a significant element of national power and security — if wisely handled, and not just diverted to narrow, jingoistic ends. (IANS)