Memoir 24: You May Kiss the Bride, the First Fight, and the Battle With Ego

By Upendra Mishra

BOSTON, 1990 — I arrived in Boston a week before my wedding, just as planned. Kamlesh Mira—my college friend from Allahabad University—and his wife Sadhna welcomed me into their home.

The moment I stepped in, it felt like a time machine had transported me back to our hostel days in Allahabad. We cooked together, joked endlessly, planned, shopped—there was joy in the ordinary, and their warmth made the days leading up to the wedding light and memorable.

Still, amidst the excitement, a quiet ache tugged at my heart.

I remembered weddings back in my village. Preparations would begin months in advance. Our large ancestral home would fill with the laughter of cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents. Children everywhere. My favorite part was taking them to our mango orchards, the lush fields, and especially the river. Those were magical days. We were children then, and foolishly believed that life would stay the same forever—that our elders would remain immortal, and we would never truly grow up.

Yet here I was, in Boston, far from home, and about to be married—not as a child play-acting rituals in the mango groves, but as a man.

And I was alone. Not a single member of my family could be here. Not one.

Indian weddings are family affairs. Everyone has a role—from the littlest child to the oldest grandparent. The bride’s side was present in full force, while on mine, it was just me. Kamlesh and Sadhna stood in for my parents, and they did so with grace and love, but I could not silence the emptiness I felt.

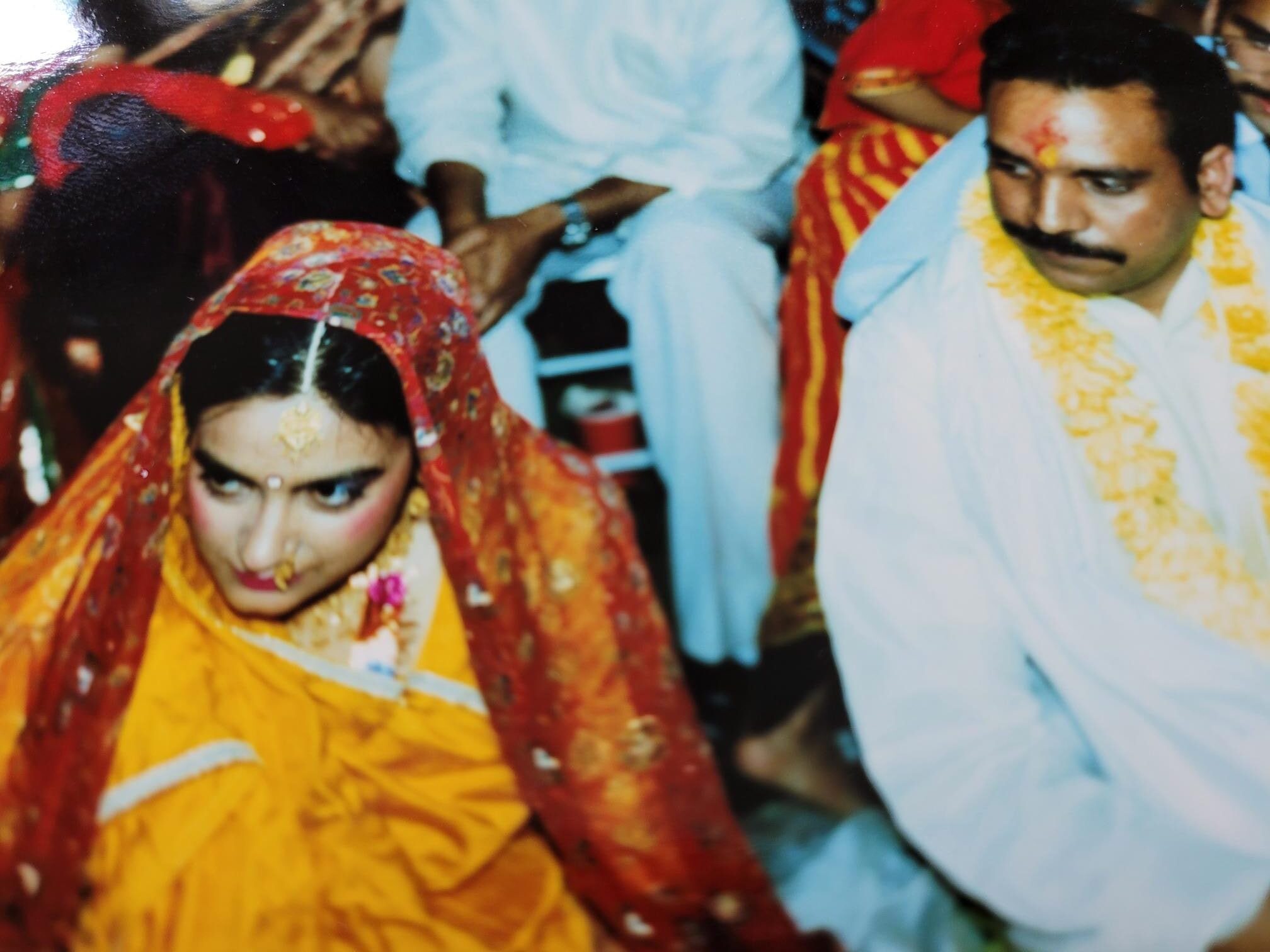

On June 19, we went to the Needham Courthouse for the legal wedding. Kamlesh, Sadhna, and I arrived first. Soon after came my fiancée with her parents and relatives. The formalities were swift. The judge declared us officially married and said, “You may now kiss the bride.”

We smiled awkwardly. That’s not how Indian weddings worked, especially not with her parents standing just feet away. We exchanged shy glances. Some traditions stay rooted no matter where you are.

My aunt in India had told me firmly, “Don’t see the bride before the wedding. It’s a bad omen.” I had originally planned to spend more time with her before the ceremony—to know her better—but I honored my aunt’s wishes. The few opportunities to grow closer in the days before the wedding slipped away.

Despite the cultural distance, some of my colleagues from UPI—both from Mexico City and Washington, D.C.—came to attend. The wedding was held at my fiancée’s home. When Kamlesh suggested we rent a limousine for the ceremony, I shook my head.

“I want to go in the car we have,” I said. “Yours is closest to mine. I don’t believe in showing off.”

“That’s a good start,” Kamlesh said with a nod.

He decorated the car with flowers the morning of the wedding. That evening, the three of us drove to her house. The ceremony lasted into the early morning hours—typical of Indian weddings. Rituals unfolded as they would in our villages, and guests dined under a tent outside. It was beautiful, even if bittersweet.

I barely remember what happened that night. I think we returned to Kamlesh’s house and the next morning, we were back at my wife’s home. The living room overflowed with boxes of gifts. In those days, there were no wedding websites or registries. We opened each gift, one by one.

Now, we were married.

She had been working as a software engineer at the time. Quietly, without telling her parents, she had resigned from her job, packed her belongings, and committed to move with me to Mexico City. A foreign land. A man she had barely spent time with. No knowledge of Spanish. No friends. No certainty. Only faith.

At the time, I didn’t realize the weight of what she had done. But now, decades later, I am awed by her courage and trust.

It reminded me of the women I had seen growing up—young brides leaving behind their entire world, moving to live with men and families they barely knew. It was common then. Expected.

But I’m a gardener now, and I know what happens when you uproot something. Even the tiniest plant, when moved, wilts. It takes time, patience, and care for it to settle in new soil.

Back then, in our Indian society, the man’s life remained unchanged. The girl’s life changed completely. This is one thing I deeply appreciate in the West—after marriage, a couple builds a life together from scratch, often starting in a small rented apartment. It’s more equal, more honest, more human.

The day after the wedding, we flew to Mexico City. Both Kamlesh and Sadhna came to the airport, along with my wife’s entire family. We were carrying twenty-eight suitcases. Yes—twenty-eight.

After arriving at Benito Juárez airport, we took three large taxis to my apartment. It was around 1 a.m. when we reached. As I stood by the door, rummaging through my pockets, panic set in.

The key was missing.

It was with my brother-in-law—back in Boston.

Thankfully, I was able to call our landlady, who came down in her nightgown, bleary-eyed but kind, and let us in. That night was the beginning of something new. I was sharing my home, my life—completely, entirely—for the first time. It was exhilarating. And terrifying.

The next morning, I had to go to work. I didn’t even have time to explain what was where, how anything worked. I just left.

When I returned that evening, I opened the door to the smell of freshly made samosas and chai. She had made them from scratch.

I stared at her. “How did you manage this?” I asked, stunned.

She smiled, “I figured it out.”

In that moment, I realized what I had been missing all these years. It wasn’t just the food. It was the feeling of someone waiting for you, caring for you, creating a home with you.

A few days later, we had our first fight.

One of my friends had gone into a coma, and I debated canceling our honeymoon to Cancun. Emotions were high already. But the real conflict came before a small dinner party.

It was to be our first outing as a couple. A friend had invited us, and we were both excited. I got dressed in my usual semi-formal attire. She got ready too. But when she stepped out of the bedroom, I froze.

She was wearing a skirt.

A wave of something primitive surged inside me. A strange, irrational fury.

“Why are you wearing that?” I asked, my voice sharp.

“This is what we wear to parties,” she replied, confused by my tone.

“I think you should change,” I said flatly.

“No. I won’t,” she responded, equally firm.

I was stunned. How could she refuse? My mind was screaming all sorts of absurd fears: People will stare at her legs! What will they think? Why is she showing her legs?

It was my village-boy brain speaking. I didn’t think about her growing up in America. Her cultural context. Her freedom.

Eventually, I relented. We went to the party. Almost all the women were wearing skirts. But I had already ruined the evening. I barely acknowledged her. She didn’t know anyone there, didn’t speak Spanish, and I—careless, oblivious—left her to fend for herself.

That night, when we came home, the argument that had been simmering boiled over.

“You’re a male chauvinist,” she said. “You have too much ego.”

Her words stung—deeply. I stood there, speechless, staring at her. A mix of anger, disbelief, and shame rose in me. Me? Ego? Chauvinist? How could she say that? I had studied in JNU, lived in the US, and worked in international journalism. I thought of myself as liberal, open, progressive.

But she had seen something I couldn’t—or wouldn’t—see. In the heat of the moment, I rejected her accusation. But over time, I came to understand something profound:

Ego is a shapeshifter.

It doesn’t always look like arrogance or pride. Sometimes, ego wears the costume of culture. Sometimes, it wraps itself in tradition, values, or even love. It says, “I’m protecting our identity” when it’s really protecting control. It says, “This is how things are done” when it’s actually saying, “I need things to go my way.”

That night, my ego wasn’t shouting, it was whispering through old memories, unchallenged norms, and inherited biases. I wasn’t thinking about her journey, her sacrifice, or her perspective—I was thinking about how she reflected on me. That’s what ego does. It pulls the focus away from connection and replaces it with control.

And it damages everything.

Ego is the enemy of love. It’s impatient when love needs time. It’s rigid when love needs flexibility. It demands, while love offers. It wins arguments but loses intimacy.

In hindsight, I realize that my wife was doing something very brave—not just in coming with me to a foreign country, but in speaking truth to someone she barely knew, someone she had chosen to trust.

She said what few dare to say. She held up a mirror. And while I hated what I saw at the time, I’m grateful now. Because ego unchecked doesn’t just harm relationships—it hardens the soul.

Over the years, I’ve come to see ego as a barrier to growth. It resists feedback. It fears vulnerability. It creates distance, even in the closest of bonds. And in that first week of our marriage, mine nearly destroyed something fragile and beautiful before it even had a chance to bloom.

We all need someone who tells us the truth—not the polished version, but the raw, painful truth. Only someone who truly cares about you will dare to do that. And only someone willing to listen will grow from it.

That night, I began to listen. Imperfectly, yes. But I began.

Stay tuned for Chapter 25: Settling in Mexico as a Couple and a Crisis at UPI.

(Upendra Mishra is the author of After the Fall: How Owen Lost Everything and Found What Really Matters, and Precise Marketing: The Proven System for Growing Revenue in a Noisy World and the managing partner of The Mishra Group. He writes passionately about marketing, scriptures, and gardening. Learn more atwww.UpendraMishra.com.)