By Upendra Mishra

BROOKLINE, MA— “Great movie experience!,” a friend said simply after watching the Bollywood blockbuster Sholay at the historic Coolidge Corner Theatre. Those three words managed to capture far more than it appeared to at first.

Because what unfolded inside that theater was not just a screening of a 50-year-old Hindi film—it was a collective time machine.

The moment the opening credits rolled and the names of Amitabh Bachchan, Dharmendra, Hema Malini, Sanjeev Kumar, and Amjad Khan appeared on the screen, the packed house erupted.

Many in the audience had first watched Sholay in India nearly five decades ago. Some had seen it multiple times. Some knew entire scenes by heart. The roar wasn’t applause—it was recognition.

Many in the audience had first watched Sholay in India nearly five decades ago. Some had seen it multiple times. Some knew entire scenes by heart. The roar wasn’t applause—it was recognition.

The energy in the theater felt alive, almost physical, as if it had taken on a shape of its own and was moving through the aisles.

For three and a half hours, the audience forgot they were in America in 2026. Suddenly, it was India in the mid-1970s again—single-screen theaters, ceiling fans, balcony seats, whistles, claps, and dialogue shouted louder than the projector.

“All those dialogues came back,” my friend said afterward. “I had no idea where those dialogues were sitting.”

I kept one eye on the screen and the other on the audience. Both were equally mesmerizing. In fact, the audience mirrored the film—anticipating punchlines, completing dialogues, roaring at iconic moments, and falling into pin-drop silence when the story demanded gravity.

I kept one eye on the screen and the other on the audience. Both were equally mesmerizing. In fact, the audience mirrored the film—anticipating punchlines, completing dialogues, roaring at iconic moments, and falling into pin-drop silence when the story demanded gravity.

The reactions were so precise they felt rehearsed. Laughter landed exactly where it had landed 50 years ago. Silence fell with the weight of tragedy.

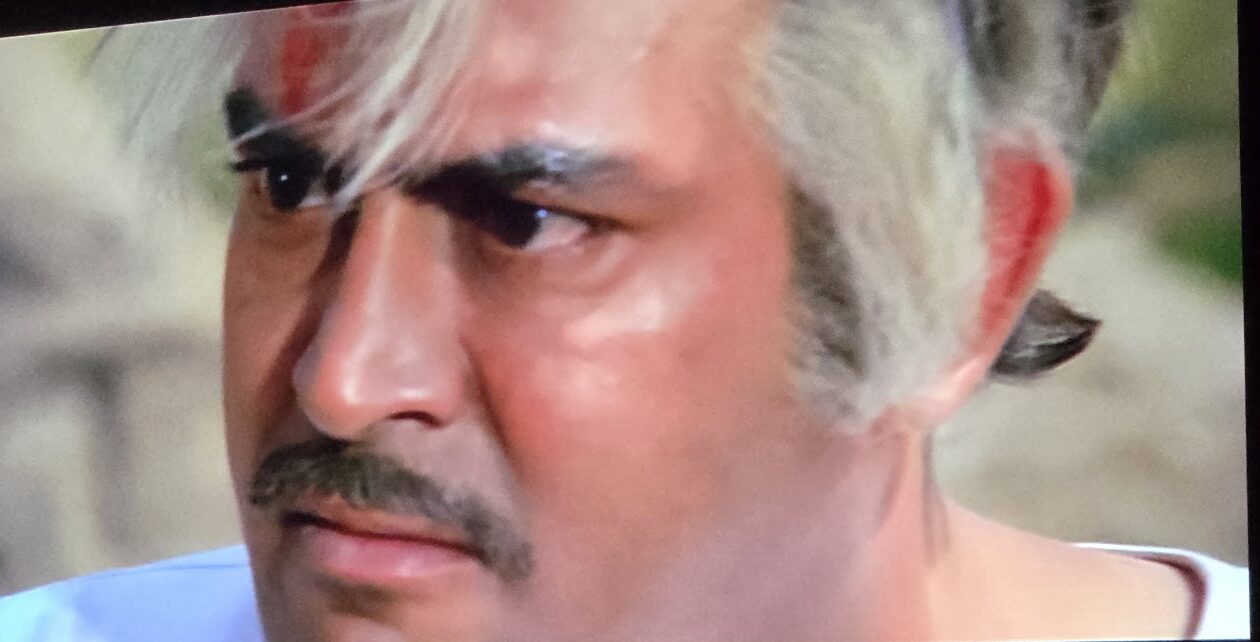

When Gabbar Singh finally appeared and growled,

“Kitne aadmi the?” (How many men were there?)

the theater exploded.

When he followed it with,

“Jo darr gaya, samjho marr gaya.” (He who fears, dies.)

the audience responded as if on cue—some cheering, some shuddering.

And when Gabbar casually asked,

“Arre o Samba, kitna inaam rakhe hai sarkar hum par?”

it felt less like dialogue and more like a call-and-response ritual passed down through generations.

Other legendary lines triggered the same collective muscle memory:

“Yeh haath mujhe de de, Thakur.”

(Give me those hands, Thakur.)

“Sooar ke bachchon!”

—still landing with perfectly timed laughter.

“Tera kya hoga, Kaalia?”

(What will happen to you, Kaalia?)

“Bahut yaraana lagta hai.”

(Seems like quite a friendship.)

“Ab goli kha.”

(Now eat a bullet.)

Then came the comedy—timeless, absurd, and irresistible.

The house erupted when Jai met mausi to arrange his friend’s marriagie with Basanti and when Veeru, drunk and heartbroken, declared in broken English:

“When I dead, police coming… in jail budhiya chakki peesing, and peesing, and peesing.”

The laughter rolled like thunder.

At the unforgettable moment when Gabbar’s gang captures Basanti, and Veeru cries out,

“Basanti, in kutto ke saamne mat nachna!” (Basanti, don’t dance in front of these dogs!) the audience laughed, clapped, and groaned all at once—knowing exactly what was coming and loving it anyway.

The comedy sparkled especially in the early scenes: Jai and Veeru’s banter, their first encounter with Basanti.

“Tumhara naam kya hai, Basanti?”

(What is your name, Basanti?)

Lines flew fast and familiar:

Jai: “Mujhe toh sab police waalon ki suratein ek jaisi lagti hain.”

(All policemen look the same to me.)

The jailor (Asrani), chest puffed out:

“Hum angrezon ke zamane ke jailor hain.”

(I am a jailor from the British era.)

Thakur, grim and resolute:

“Yeh haath nahi, phansi ka fanda hai.”

(These are not hands, but a noose.)

Kaalia, pleading for his life:

“Saab, maine aapka namak khaya hai.”

(Sir, I have eaten your salt.)

Written by the legendary Salim–Javed, these lines are not just dialogue—they are the backbone of Hindi popular culture. They live in everyday speech, political speeches, comedy shows, and family conversations. Hearing them in a theater again felt like meeting old friends who hadn’t aged a day.

Written by the legendary Salim–Javed, these lines are not just dialogue—they are the backbone of Hindi popular culture. They live in everyday speech, political speeches, comedy shows, and family conversations. Hearing them in a theater again felt like meeting old friends who hadn’t aged a day.

But amid all the thunderous dialogue and laughter, the theater’s mood softened whenever Sholay traded words for glances.

Jai and Radha’s (Jaya Bhaduri) love wasn’t declared with a flourish or a song. Instead, it lived in the unspoken moments—the way Jai’s eyes lingered just a beat too long when Radha stood in the courtyard, or how she paused by the kerosene lamps at dusk while he played a harmonica in the fading light. In those scenes, there was no dialogue, just presence and possibility.

Radha wore her widow’s white sari with quiet dignity; Jai carried his past with a shrug and a harmonica tune. When they shared a moment, the camera often cut away before either spoke, as though the characters themselves feared interrupting what could not yet be named. In the Coolidge Corner theatre, the audience held its breath. Not a single person yelled. Not a single phone lit up. Only silence, thick with feeling.

Radha wore her widow’s white sari with quiet dignity; Jai carried his past with a shrug and a harmonica tune. When they shared a moment, the camera often cut away before either spoke, as though the characters themselves feared interrupting what could not yet be named. In the Coolidge Corner theatre, the audience held its breath. Not a single person yelled. Not a single phone lit up. Only silence, thick with feeling.

If Jai and Radha’s love was silence, Veeru and Basanti’s was music.

Their romance burst onto the screen with laughter, teasing, and pure cinematic joy. Basanti—talkative, fearless, endlessly alive—found her match in Veeru’s swagger and vulnerability. The temple scene, where devotion mixed with playful romance, drew smiles and laughter across the audience. The mango-picking scene, light and flirtatious, felt like summer itself—carefree, fleeting, and irresistible.

And then came Veeru teaching Basanti how to shoot.

What could have been just another plot moment became something tender and symbolic. Veeru guiding Basanti’s hands, teasing her, encouraging her, trusting her—it wasn’t just romance, it was partnership. Basanti was never reduced to a damsel. She learned, she resisted, she stood her ground. The audience laughed, yes—but they also recognized something quietly progressive for its time.

In those quieter stretches of Sholay, Brookline’s laughter receded, replaced by a hush more profound than any shouted dialogue could ever command.

A Film That Refuses to Fade

Nearly five decades after its original release in 1975, Sholay continues to captivate audiences. The Coolidge Corner Theatre screening sold out its Saturday show, prompting organizers to add a second screening on Sunday, February 8, 2026.

Widely regarded as the most influential Hindi film of all time, Sholay starred Amitabh Bachchan, Dharmendra, Sanjeev Kumar, Hema Malini, Jaya Bhaduri, and Amjad Khan. Though the film marked its 50th anniversary in 2025, its grip on the collective imagination remains unshaken.

“It’s no surprise the show is sold out,” said Preetesh Shrivastava, president of Hindi Manch and a lifelong Sholay devotee. Shrivastava famously celebrated the film’s 50th anniversary at Boston’s Hatch Shell last year—displaying Sholay posters on his car, whose license plate reads “SHOLAY.”

“For fans like me, Sholay is not just a movie; it’s an experience,” Shrivastava said. “Ramgarh feels like a real place to us.”

He pointed out that Sholay is remembered not just for its stars, but for its world. “Most films are remembered for a few characters. In Sholay, you can name ten—easily. Even Dhanno, the horse, is more famous than the heroes of many other movies.”

Directed by Ramesh Sippy and written by Salim–Javed, Sholay was conceived as India’s grand action-adventure—a genre-defining “Curry Western” inspired by Hollywood classics. At its heart is a retired police officer who recruits two small-time crooks to hunt down Gabbar Singh, a villain who redefined cinematic evil through Amjad Khan’s unforgettable performance.

One unfortunate thing with the screening of the film was that the Coolidge screening on Saturday did not feature the newly restored director’s cut, presented in stunning 4K by the Film Heritage Foundation in collaboration with Sippy Films and L’Immagine Ritrovata in Italy. The restoration had claimed to preserves the original 70mm aspect ratio and reinstates the original ending and scenes once lost to censorship.

Three hours and twenty-six minutes later, when the lights came back on, people didn’t rush for the exits. They lingered. Smiled. Quoted lines. Took photos.

Because some movies end when the screen goes dark.

Sholay ends only when the audience stops speaking its language—and judging by Brookline that night, that day is nowhere in sight.