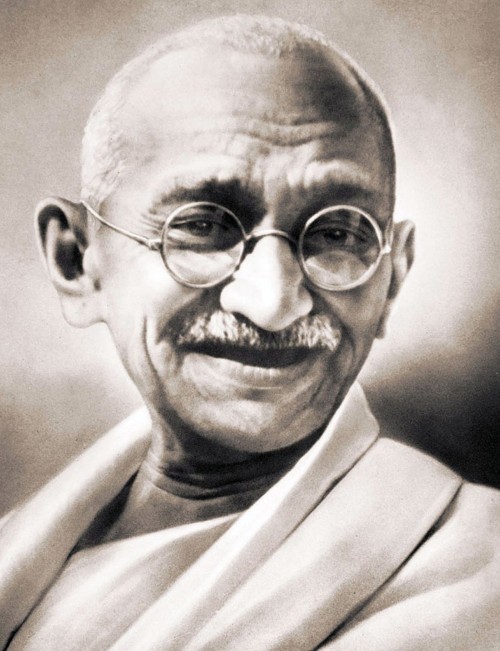

By Amit Khanna

Much before he turned a Mahatma, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was a strong proponent of anarchy. Anarchy is a political school of thought which aspires for a stateless society based on voluntary self-governance. Over centuries, many philosophers — like Laozi, the founder of Taoism in 6th century BC China, Diogenes and the Cynics and Aristotle in 4th century BC Greece, or even some sayings in Manusmriti from 3rd century India — have mentioned this ideal state. German philosopher Immanuel Kant called anarchy a state governed by law and “freedom without force”.

However, despite the thought existing through eras, modern anarchy was first proposed in Europe in the 18th century. The British writer and thinker William Godwin is considered its founder. Many revolutions, including the French, Russian and even India’s early freedom struggle, have espoused this ideal. Some writings of Karl Marx talk of this concept. In modern India, freedom fighter Lala Har Dayal of the Gadar Party, a contemporary of Gandhi, was another supporter of anarchy in the beginning of the 20th century.

However, despite the thought existing through eras, modern anarchy was first proposed in Europe in the 18th century. The British writer and thinker William Godwin is considered its founder. Many revolutions, including the French, Russian and even India’s early freedom struggle, have espoused this ideal. Some writings of Karl Marx talk of this concept. In modern India, freedom fighter Lala Har Dayal of the Gadar Party, a contemporary of Gandhi, was another supporter of anarchy in the beginning of the 20th century.

Gandhi, in his formative years and during his education in England and stay in South Africa, was exposed to the great thinkers of the world, especially the West. However, unlike many of his contemporaries, this broadening of vision did not alienate him from either his roots or his spirituality.

He was first influenced by the Anarchism of another contemporary, the great Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy, quite early in life (in the 1880s, when he was a law student in London). Tolstoy’s ideal of “simplicity of life and purity of purpose” influenced Gandhi deeply. The “love as law of life” and principles of non-violence, that is based on love for the entire mankind, were deeply embedded in the writings of Tolstoy. Both Gandhi and Tolstoy adopted the idea of love to solve the problems of life.

Gandhi has written that reading the “The Kingdom of God is Within You” had cured him of scepticism and made him a firm believer in Ahimsa. In fact, Gandhi and Tolstoy corresponded with each other in 1909 and 1910. This exchange of letters (now in the public domain) clearly shows that Gandhi held Tolstoy in high esteem and shared a similar philosophy, and that both were firm believers in non-violence.

During his days in South Africa, Gandhi actually formulated his views on a stateless society and it was first exhibited in his fight against British colonialism. He was also profoundly impressed by Godwin (1756-1836). When Gandhi came back to India in 1915, he was convinced that there was no difference between the colonial South African government and the Imperial British India government.

Other thinkers who influenced Gandhi’s belief in anarchy included British essayist and writer John Ruskin (1819-1900). His book “Unto This Lust” was one of the most significant influences on the Mahatma’s later life. Similarly, he drew inspiration from the writings of Henry David Thoreau, the British poet Percy Shelly and later from the writings of Romaine Roland (and his subsequent interaction with him), and even Swami Vivekananda. Unlike other intellectuals of his time (and later) Gandhi wore his knowledge lightly. He was, however, through rigid self-discipline, able to distil his own doctrine from his vast reading of others’ thinking.

Gandhi’s concept of Satyagraha and his entire Civil Disobedience movement is a clear manifestation of his faith in anarchy. Quite contrary to the concept of Ram Rajya being propagated by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and other Hindu thinkers, Gandhi’s vision of Ram Rajya was based on freedom, justice, human rights, equality and non-violence (and was perhaps closer to the Vedic and early Hindu concept of just governance).

In fact, Gandhi’s tolerance was more of Sarva Dharma than of supremacy of one religion over another. This interpretation of governance is truer to the one mentioned in the Vedas, Ramayana and Mahabharata. If we carefully examine this concept of an ideal social order, Gandhi propagated a society free of state control to the maximum extent possible in a civilised world. As a corollary, Gandhi’s philosophy, however questionable it may be, believed that the state must ensure minimum exploitation and give its citizens maximum freedom.

Unlike his favourite political disciple Jawaharlal Nehru, who was a self-confessed non-believer, Gandhi remained a deeply religious person. He was, however, uniquely divided in his views on spirituality, morality and freedom and they, along with other dualities like ancient wisdom and scientific modernism, existed simultaneously in his thoughts and life, often in conflict with each other but never manifesting in any form of violence or hate.

Of course, the Mahatma always believed in the fundamental supremacy of a divine moral code — God’s will being the ultimate authority. He once said that if any man-made law violates the law of God, men should have the right to defy such a law. Yet his faith in Hinduism never came in conflict with his quest for freedom or the truth. He maintained his stance on politics (indifference to party politics), communal harmony, non-violence and individual freedom right till his last breath, but was in a prayer meeting with “Ram naam” on his lips when he was assassinated.

His famous advice to wind up the Indian National Congress after independence was, in a way, an expression of his belief that existing structures of governance were too ossified to give citizens the true freedom they deserved. Self-control and not state control was his oft-repeated mantra. Yet, sadly, no government, including those led by his staunch followers, gave up control. In fact, with every successive government, more authority was vested with the state. The obsession with the Soviet model of state control and domination actually damaged any notion of the citizenry’s freedom.

The height of state control was reached during Indira Gandhi’s infamous Emergency. There have been sporadic attempts to revive Gandhi’s notion of anarchy by people like Jaiprakash Narayan and recently Anna Hazare (the original Aam Aadmi Party was founded on this principle, but gave it up immediately after tasting its first electoral victory).

The present government came to power on a plank of equitable justice and development for all. However, internal party pressures and contradictions are taking the Prime Minister away from this stated mission. Every day one hears of government trying to impose restrictions or its ideological will on people. I may be in a very small minority who believes that somewhere in his heart Narendra Modi aspires to be a statesman. But to walk the talk, he needs to get rid of his baggage. He will have to work harder to rein in his jingoistic followers who are hijacking his polity.

Ram Rajya will come, as Mahatma Gandhi said, by giving up control and not by mere symbolic gestures. The essence of Ramayana is equitable justice, self-sacrifice and humility in thought, deed and action. Gandhi strove for this ideal. Sabka Saath. Sabka Vikas. Sabka Vichar. Will we ever get it?(IANS)