By Vikas Datta

“Murder is a crime. Describing murder is not. Sex is not a crime. Describing sex is,” American critic Gershon Legman advised writers but never realised it was sex that raked in both big money and popularity — as we well know from “Fifty Shades..” or some of Mills and Boon’s more explicit titles. And despite how bad or tasteless the sex element is — as some journalists realised.

The sex aspect was however a big deal half a century ago — when the bestseller lists were populated by Jacqueline Susann (“She felt herself responding to his embrace with an ardor she had never dreamed she possessed, her mouth demanding more and more…”) and Harold Robbins (“Her mouth was warm and moist and still tasted of orange soda. Then he moved his head and his lips were travelling down her body…”).

And then came a book by alluring Penelope Ashe, who contended that the exotic sexual behaviour it portrayed was the norm in suburban America.

“Naked Came the Stranger” (1969), about a string of indiscriminate — and often lethal (for the partner) — sexual liaisons of Gillian Blake, a radio show host in suburban New York seeking revenge on her allegedly cheating husband William, also became a bestseller.

Perhaps, readers were entranced by its blurb which said that “men and marriages fall at her feet” and after listing probable reasons for “her unleashed demons”, says her “trail is strewn with the corpses of marriages gone bad, cracked open by the pressure, unable to survive them when… naked came the stranger”.

In the story “of men who are weak and one woman who is strangely willing”, the victims include a war veteran, a rabbi (in a ludicrously comic episode), a Mafia prince, an interior decorator, an accountant facing bankruptcy, a hippie (another uproarious scene), an abortion doctor, a former boxer and several others. Interspersed are transcripts of Gillian and her possibly philandering husband’s “Billy and Gilly Show”.

But there was more to this book.

Ashe was only a front and the book was a hoax — a creatively ingenious effort by a band of two dozen journalists in the daily paper Newsday seeking to highlight and mock the shallow, sex-obsessed literary culture of late 1960s America.

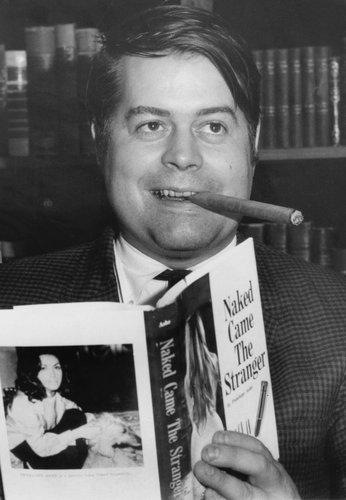

At its heart was Newsday columnist Michael Robinson ‘Mike’ McGrady (1933-2012), who wanted create the worst sex novel ever. While the idea came when relaxing with colleagues in a bar after work on June 12, 1966, playing a key role also were two recent personal experiences — an interview with Robbins, who had got a $2 million advance for his next book on its mere synopsis, but revealed it was actually only on basis of the two-word title (“The Adventurers”) and McGrady’s “attempt to read (Susann’s) ‘Valley of the Dolls, a task as formidable and challenging in its way as reading, oh, ‘Ulysses’…”

And as McGrady tells us, in an uproariously humorous introduction to the 21st century edition, at home that night and nursing a hangover, he sat down to frame an invitation to interested colleagues and, more importantly, frame the guidelines.

And as McGrady tells us, in an uproariously humorous introduction to the 21st century edition, at home that night and nursing a hangover, he sat down to frame an invitation to interested colleagues and, more importantly, frame the guidelines.

Based on a thorough analysis of the plots of Robbins, Susann and others, he concluded that there was to be “an unremitting emphasis on sex” (they finally settled for two assignments per chapter), and “true excellence in writing will be quickly blue-penciled into oblivion”. The invitation was sent not only to the paper’s writers, but “to anyone who had been seen rapping on a typewriter: Secretaries, editors, repairmen, anyone”.

And while McGrady had been apprehensive of the responses, they came in thick — and the 25-odd member (five of them women) team had a tough time at story conferences, debating and shooting down some too far-fetched suggestions. Once the writing was done, it was heavy editing to weed out anything too well-written. As The New York Times put it, it involved “cutting out words of more than three syllables, all symbolism, most character descriptions and 90 percent of all references to nature”.

Women played a major role — the female protagonist got her name on the suggestion of McGrady’s wife Corinne who said this was the “kind of the name they always use in dirty books”, a woman editor believed that the title should definitely have the word “naked”, and a woman reporter said the dedication should be changed from mother to “Daddy” as it seemed “more Freudian”.

And then McGrady roped in his glamorous sister-in-law Billie Young (a fan of Robbins and Susann) to play Ashe, and she floored publishers and reporters alike with her style.

Published by a maverick publisher, the book was a runway success — even after some members of the syndicate revealed their part. McGrady, who had become the kingpin of the most successful literary hoax of the 20th century, went on to write “Stranger than Naked or How to Write Dirty Books for Fun and Profit: A manual”.

The book is still a cult classic — but is it as shocking now? (IANS)