BROOKLINE, MA — Some people watch Sholay. Preetesh Shrivastava lives it.

Nearly 50 years after the legendary Bollywood film first thundered onto the screen, Sholay continues to inspire devotion that borders on pilgrimage—and Shrivastava may be one of its most passionate modern-day custodians.

President of Hindi Manch and a lifelong admirer of the film, Shrivastava’s love for Sholay is not limited to repeat viewings or favorite dialogues. It travels with him, quite literally, on the road, in photographs, and across continents.

His car’s license plate says it all: SHOLAY.

From the Screen to the Hills of Ramgarh

For generations of fans, Ramgarh—the fictional village at the heart of Sholay—has felt like a real place. For Shrivastava, it was important to see it for himself.

“I visited Ramgarh of Sholay, which is actually a village called Ramanagara, situated about 50 kilometers from Bangalore on the Bangalore–Mysore highway,” Shrivastava said. “Ramanagara is known for its dramatic, boulder-strewn hills. The spot became a tourist attraction, with many hills in the region nicknamed ‘Sholay Hills.’”

Walking among those rugged landscapes, Shrivastava stood where cinematic history was made—where Jai and Veeru’s friendship unfolded, where Gabbar Singh’s menace echoed, and where Indian cinema found one of its most unforgettable backdrops. He documented the visit with photographs, adding to a personal archive that already includes treasured original images from the film.

This is not casual fandom. It is curatorial.

When Love for a Film Becomes Cultural Stewardship

Shrivastava’s admiration for Sholay blends affection with insight. He speaks not only of stars but of storytelling, character-building, and cultural permanence.

“Most movies are remembered for a few characters,” he said. “Sholay is so iconic that fans can name at least ten. Even the mare, Dhanno, is more famous than the hero or heroine of many other films.”

It’s a line delivered with a smile—but it carries truth. The film didn’t just create heroes; it created a universe. Characters like the jailor, Soorma Bhopali, and Sambha entered everyday language, permanently shaping popular culture.

Shrivastava’s enthusiasm has found public expression too. Last August, during Sholay’s 50th anniversary year, he commemorated the milestone at Boston’s Hatch Shell, displaying Sholay posters on his car—turning heads, sparking conversations, and delighting fellow fans who immediately understood the reference.

“For fans like me, Sholay is not just a movie,” he said. “It’s an experience we want to enjoy again and again.”

A Sold-Out Reminder of a Film’s Enduring Power

A Sold-Out Reminder of a Film’s Enduring Power

That experience is now drawing packed houses once more. A screening of Sholay at the Coolidge Corner Theatre has sold out for Saturday, prompting organizers to add a second screening on Sunday, February 8, 2026—a remarkable achievement for a film released in 1975.

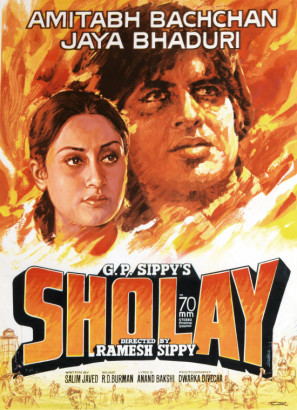

Directed by Ramesh Sippy and written by the legendary duo Salim–Javed, Sholay starred Amitabh Bachchan, Dharmendra, Sanjeev Kumar, Hema Malini, Jaya Bhaduri, and Amjad Khan. Conceived as India’s most ambitious action-adventure film, the genre-defying “Curry Western” redefined scale, sound, and storytelling in Hindi cinema.

The Coolidge screenings feature the recently restored director’s cut, presented in 4K after an extensive restoration by the Film Heritage Foundation, Sippy Films, and L’Immagine Ritrovata in Italy. The version preserves the original 70mm aspect ratio and includes the original ending and previously censored scenes—making it a rare opportunity to experience Sholay as closely as possible to its original vision.

Why Sholay Still Sells Out—and Still Matters

The film runs over three hours. It belongs to another era. And yet, audiences continue to fill theaters.

For fans like Preetesh Shrivastava, the reason is simple: Sholay never stopped being relevant. Its themes of friendship, sacrifice, justice, and moral courage still resonate. Its dialogues still spark laughter and applause. Its landscapes—whether on screen or in Ramanagara’s hills—still feel alive.

As the Coolidge screenings sell out and a new generation discovers the film, Shrivastava’s devotion feels less like nostalgia and more like preservation.

Some movies fade with time.

Some become history.

And a rare few—like Sholay—become a lifelong companion, complete with photographs, pilgrimages, and even a license plate.

Yeh dosti… clearly isn’t going anywhere.