By Upendra Mishra, Author of After the Fall and Precise Marketing

BOSTON–After the dust finally settled—the secret account exposed, the manager gone, the union calmed, and the lawsuit quietly winding its way through the courts—I found myself in unfamiliar but surprisingly welcome territory.

What had begun as a firestorm ended with a promotion: I was no longer just overseeing news coverage for UPI in Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean—I was now managing the entire network of bureaus in the region.

Along with the editorial responsibilities came new duties: chasing down unpaid subscription dues from newspapers and TV stations, managing office operations, and representing UPI’s interests across a dozen countries. It meant more travel, more responsibility—but also, a chance to finally breathe. I wasn’t constantly chasing breaking news anymore. I was out meeting editors, walking through newsrooms, sharing meals, shaking hands. After the chaos, it felt like freedom.

I found myself in places I had only read about in wire reports—San José, Havana, Tegucigalpa, Managua, San Salvador, Guatemala City and many more. Each trip brought me face-to-face with the editors and publishers who relied on UPI’s Spanish-language service, most of them fiercely loyal subscribers, some months behind on payments, all of them eager to talk.

These visits weren’t just about collecting dues—they were about building relationships, understanding local challenges, and strengthening UPI’s foothold in a region where news moved fast and trust moved faster. I loved it. Walking through cramped, sunlit newsrooms with humming typewriters and cigarette smoke curling in the air, I felt at home. The pressure of breaking news had lessened, but the reporter in me never quite shut off. I was always watching, always listening—always on the lookout for the next story waiting to be told.

Traveling across Latin America on an Indian passport in the 1980s early ‘90s was an adventure in itself—often thrilling, sometimes harrowing. Back then, very few Indians visited these countries, and I was frequently the only Indian many people had ever seen. This was also the height of the Cold War, and much of Central America had become a geopolitical battleground. Leftist guerrilla groups—some supported by the Soviets—fought against U.S.-backed right-wing military regimes. India, due to its strong diplomatic and defense ties with the Soviet Union at the time, was widely perceived in the region as being in Moscow’s corner.

That made me a curiosity—and occasionally, a suspect.

At nearly every immigration checkpoint, I was met with confusion and suspicion. Officers would study my Indian passport, then study me—trying to figure out what I was really doing there. Was I a journalist, as I claimed? Or something else entirely? More than once, I caught someone whispering, “Soviet spy.”

One particularly frightening encounter took place at the Guatemala City airport. Upon arrival, I was pulled aside and taken into a small, windowless interrogation room. No questions were asked—just long stares and muffled conversations behind closed doors. After about an hour, a pair of soldiers came in, boots first. They didn’t say a word. They kicked me hard a few times, seemingly as a test, a warning, or simply out of suspicion. I tried to explain my role with UPI, showed my credentials, and after some time—and perhaps realizing I had no political agenda—they let me go. Bruised, shaken, but free.

Despite that experience, I didn’t let fear stop me from exploring Guatemala further. On another visit, I decided to take a few days off and head to Lago de Atitlán—one of the most breathtaking places I’ve ever seen. Nestled among volcanoes and mountains, its shoreline dotted with small Indigenous villages, it felt like a world untouched. The lakeside town was surprisingly lively, filled with European and American backpackers, artists, and seekers. For a moment, it felt like I had stepped into a sleepy corner of northern Europe.

To get there, I traveled by bus, stopping first in Antigua, the old colonial capital of Guatemala. I remember it for two reasons: the stunning cobbled streets and historic buildings—and the fact that I spent the night in a clean (well, not so clean), cozy motel for just two U.S. dollars. Even back then, that felt almost surreal.

The next morning, I caught another bus bound for Lago de Atitlán. As we made our way through dense jungle roads, the bus suddenly screeched to a halt. A military checkpoint. Heavily armed soldiers motioned for everyone to get off. One by one, passengers were interrogated, their bags searched thoroughly. When it was my turn, the familiar routine began again. The Indian passport raised eyebrows. Suspicion crept in.

“What is an Indian doing in Guatemala?”

“Are you with the Soviets?”

I had become used to this line of questioning, but it never stopped being uncomfortable—or dangerous. In their eyes, I didn’t fit. And in those days, not fitting in could be a serious liability.

Not every experience in Guatemala was filled with suspicion or danger. In fact, some were surprisingly heartwarming—and even a little surreal.

On one of my work trips back to Guatemala City, I scheduled a visit to the office of one of the country’s leading daily newspapers to meet with the editor and publisher. I called ahead to set up the appointment, and a secretary answered. Judging from her tone—and perhaps from my name or my accent—she quickly figured out that I was Indian. Her voice lit up with curiosity and excitement. “An Indian? Really?” she said with genuine fascination.

She seemed thrilled by the idea of someone visiting from India, and we confirmed a time for the meeting. I didn’t think much more about it—until I arrived at the newspaper office.

To my surprise, the same secretary was waiting for me outside the building, holding a large flower garland—like I had just returned victorious from a long journey home. Before I could even say hello, she rushed toward me with open arms and hugged me warmly, almost ceremonially.

I was stunned—shocked, really—but also deeply touched. In the midst of a region that often viewed me with suspicion, here was someone who greeted me like an old friend, or perhaps how a guest might be welcomed in India. It was one of those rare, unexpected gestures of human kindness that reminded me how culture and warmth can sometimes transcend borders—even when politics, fear, and history seem to divide them.

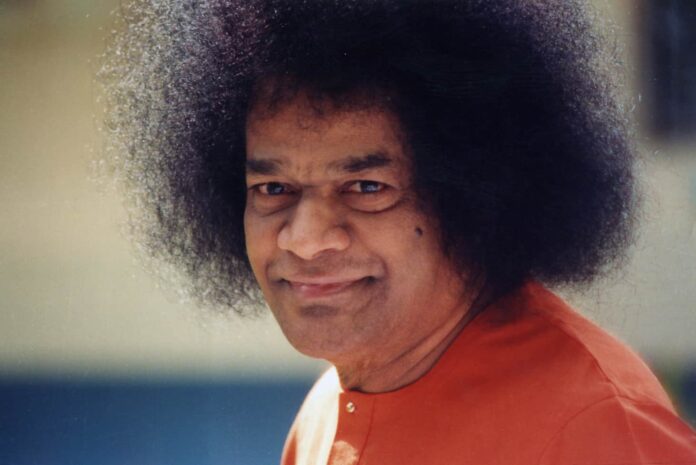

She introduced herself with a wide smile and a gentle reverence in her voice. “I’m a devotee of Sai Baba,” she said proudly. “You are the first Indian I have ever met—from the land of Sai Baba.”

Her excitement was contagious.

At first, I was stunned to hear Sai Baba’s name here—spoken with such familiarity—in the middle of Guatemala City. But she wasn’t alone. As we spoke, she told me about the growing community of Sai Baba followers in the country. It was more than admiration—it was devotion.

She spoke of him as a spiritual guide, a miracle worker, a divine presence. Later, I would learn that across Central America, in countries like Guatemala, El Salvador, and Costa Rica, Sai Baba had developed a large and deeply committed following. Year after year, hundreds of these devotees would make the long and expensive pilgrimage to Puttaparthi, the small town in southern India where Sai Baba’s ashram was located.

My journalistic instincts kicked in. I began to dig a little deeper into this curious cross-cultural connection. What I discovered was fascinating. Not only had Satya Sai Baba—as he was formally known—amassed millions of followers around the world with his message of universal love, service, and devotion, but there was also quiet encouragement from the Indian government for this global spiritual movement.

While never officially acknowledged, it was no secret that the Indian foreign ministry saw this “soft power” as a valuable diplomatic asset. Devotees brought more than reverence—they brought foreign currency, spent generously in India, and returned home with a spiritual connection to the country that extended far beyond politics or trade.

Born in 1926 in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, Sai Baba claimed from a young age to be a reincarnation of an earlier saint, Shirdi Sai Baba. He rose to prominence in the 1950s and 60s, drawing crowds with claims of miracles—manifesting sacred ash (vibhuti), healing the sick, materializing jewelry and sweets.

But beyond the spectacle, what sustained his global appeal was his message: service to humanity, unity of all religions, and personal transformation through devotion and discipline. By the 1980s, Sai Baba’s ashram was a thriving spiritual hub attracting tens of thousands of visitors each year, including heads of state, scientists, celebrities, and, as I now saw, believers from Latin America.

To meet someone so deeply touched by an Indian spiritual leader—especially in a country where I had just been kicked and interrogated as a suspected spy—was not only humbling but profoundly moving. It reminded me that identity isn’t always judged by politics or passports. Sometimes, it’s shaped by faith, connection, and an invisible thread of humanity that runs deeper than borders.

Memoir 28: El Salvador – Into the Heart of a Country at War: What Guatemala tested through suspicion, El Salvador would challenge through fire. As civil war raged and death squads ruled the streets, I found myself navigating one of the most dangerous beats in Latin America—armed with only a notebook, a press badge, and a deep belief in the power of truth. But no training could have prepared me for what I would witness next.

(Upendra Mishra is the author of After the Fall: How Owen Lost Everything and Found What Really Matters and Precise Marketing: The Proven System for Growing Revenue in a Noisy World. He is managing partner of The Mishra Group. Learn more at www.UpendraMishra.com)