By Vikas Datta

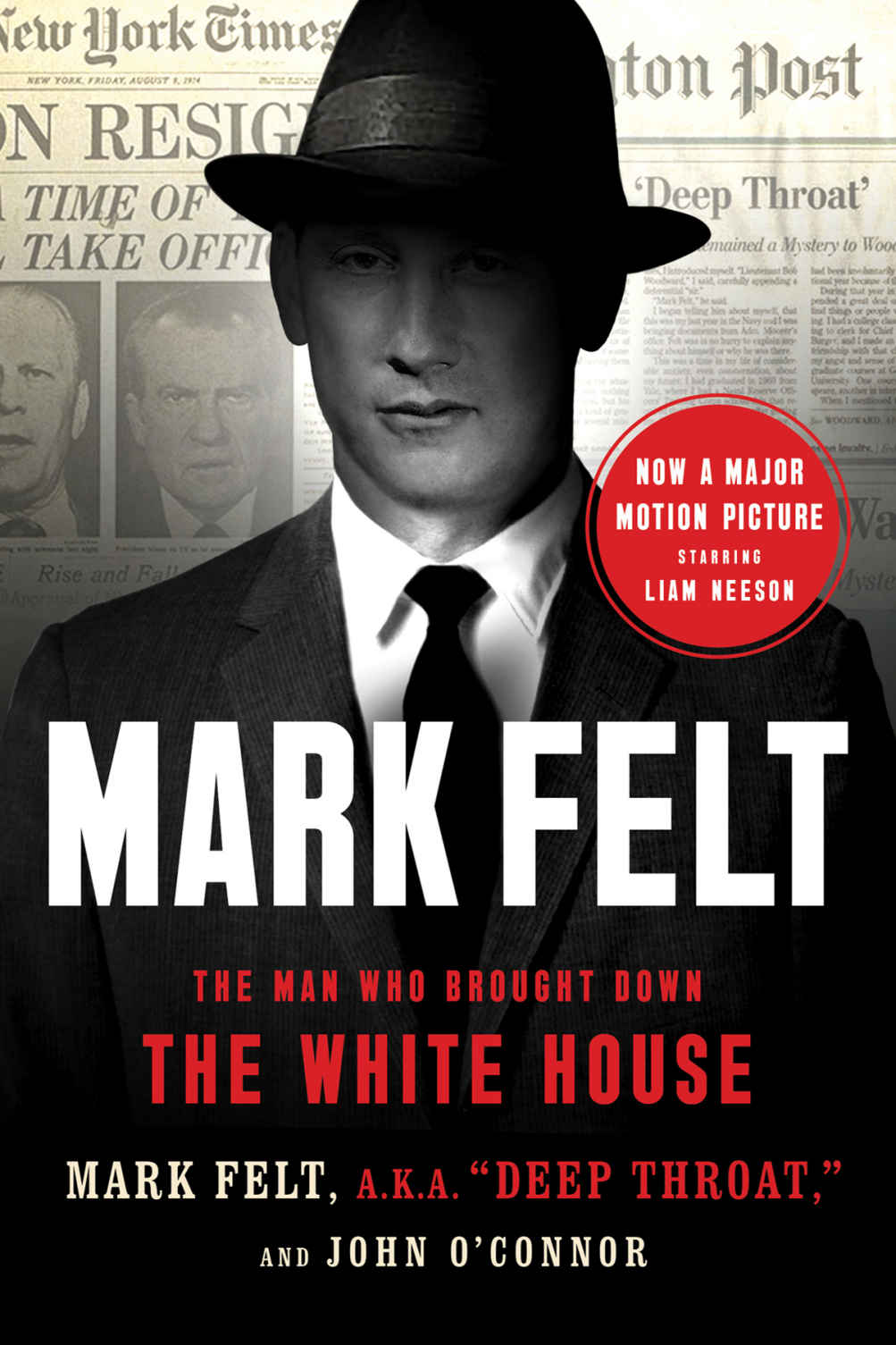

Title: Felt: The Man Who Brought Down the White House; Author: Mark Felt (with John O’Connor); Publisher: Ebury Press; Pages: 368; Price: Rs 499

An American President is elected in a divisive election, in which a section of his supporters used purported criminal means – including stealing or trying to steal the opposition party’s confidential documents; the FBI’s inquiry into the matter is stymied by the new administration but leaks and dogged journalists bring out the scandal into the open. Donald Trump’s US?

No, this was the US in 1972-73, the time of President Richard Nixon – and Watergate.

No, this was the US in 1972-73, the time of President Richard Nixon – and Watergate.

Though there are many similarities between the two times and tenures, there is one crucial element missing from the present period – a senior FBI official who undertook an unprecedented, lone and surreptitious operation to ensure the cover-up failed.

It is in this book we learn his full story – and why it is important, as well as his likely motivations.

We have known him long as “Deep Throat”, a name inspired by the contemporary pornographic film and given to him at The Washington Post, whose reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein he guided in their investigation. But even after FBI’s then Deputy Director Mark Felt revealed his identity in 2005 – over three decades later, we still don’t know much about why he played this mysterious role – as can be seen in the film version of Woodward and Bernstein’s classic “All the President’s Men”.

Attorney and author O’ Connor, who successfully worked out Felt’s identity in 2005 and convinced him to confirm it, tries, in this book, to solve the mystery behind the man, who worked towards the exposing one of American politics’ biggest scandals – but did not even seek acknowledgment for what he did.

Watergate’s denouement, leading to Nixon resigning in disgrace and going on to refashion politics, media and law enforcement – and their relationships – far into the future (Well, at least till our “post-truth” world). But why Felt did what he did and did not reveal it till he was was over 90 has been perplexing.

Twice passed over to head the FBI – which could have contributed to his decision, Felt did not even tell his family about his secret exploits, leave alone in his (largely unknown) memoirs, published in the early 1980s.

But O’Connor, in this revised and updated version of his 2006 recasting of Felt’s autobiography with additional information from Felt and his family and other sources, tries to solve what led to this career FBI operative to become a secret informer to political shennigans.

Though Felt is reticent to the extreme – even in the chapter on Watergate, he makes no mention of his secret counselling of Woodward. All he says is that he must give some credit to the press without which “much of the White House involvement in the break-in (in to the Democrat National Committee office in Watergate) and the subsequent cover-up) would have never been brought to light”. Also, “people will debate for a long time whether I did the right thing by helping Woodward”.

O’ Connor, noting Felt’s memories had faded due to dementia, is forced to reconstruct with the help of his formerly secret files and interviews with family and colleagues, answers to “three important aspects” – “why he initiated his high-stakes garage meetings with Woodward, how he planned and managed those meetings, and how he escaped detection at the FBI”.

And while he tries to do so, to to the best of his ability and understanding (Woodward’s own “The Secret Man: The Story of Watergate’s Deep Throat”, which came in wake of Felt revealing himself, is also a useful supplement), the major motivations can be discerned from the recounting of Felt’s career in the FBI.

As we learn, Felt was a competent, conscientious and dedicated FBI operative – at the cost of his family life – who unearthed Nazi and Soviet spies, tackled mobsters, cut through red tape to solve cases and get information, got on well with his legendary chief J. Edgar Hoover, and always opposed political interference in law enforcement.

While these could go a long way in explaining why Felt fought his lonely and secret battle, his example is all the more relevant today when political leaders invoke all kinds of justifications for their questionable actions and suborning of law and justice for the purpose.

This makes the book a must read for any one who cares about rule of law and accountability. (IANS)