By Vishnu Makhijani

New Delhi– It was once home to some 130 textile mills employing 300,000 workers but then came the Great Bombay Textile Strike of 1982 over salary increases and wages that prolonged for 18 months and triggered the end of the once thriving industry. In the 1990s came the revival some say it was the hidden agenda behind the shutdown.

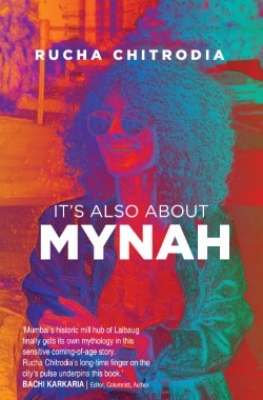

Today, Lalbaug in central Mumbai is the heart of a thriving commercial district of plush corporate offices, financial institutions, design studios, ritzy malls, fancy bars and high-end hotels. Into this gentrification, author Rucha Chitrodia weaves the story of a young girl’s coming of age that in many ways reflects the transformation of what could easily have deteriorated into the city’s underbelly.

“I wanted to capture the lives of people, both regular and irregular, at the micro level alongside the larger social context of a particular place and time–in this case Mumbai and the economically and socially valuable age of its former textile mills industry. Its clangour, strident at first and then deafeningly silent following the unexpectedly unending labour strike of the early 1980s, Chitrodia, a journalist of 26-years standing, told IANS in an interview about her debut novel, “It’s Also About Mynah” (Amaryllis), that takes a look at modern, formless equations and almost-romances.

If it’s about heartbreak, it’s also about healing and about the exciting continuum of human ups and downs.

What happened in Lalbaug was perhaps the first example of “disruption”, a “word used ad nauseum today considering the revolutionary impact of the internet on life as we know it–has always been a universal human experience through every epoch (if not at the current speed of light),” Chitrodia explained.

When a young Mynah moves to Mumbai to join an ad agency, much against the wishes of her paranoid father, she is reluctantly catapulted into adulthood. A ghosting boyfriend, struggles at her workplace, a meeting with her runaway birth mother… She gets acquainted with life’s truths as a paying guest in the beautiful and lonely Aruna’s flat in the city’s old mill district, which has its own story to tell.

To this extent, the book looks at the impact of disruption in each character’s journey juxtaposed against the fate of the city’s mills and the aftermath. The central character of Mynah, for one, would not have moved into Lalbaug and got a job in Parel if not for the labour strike and parcelling off of land in these two erstwhile central Mumbai mill hubs to the real estate industry. The land would not have been repurposed to make way for residential highrises and corporate offices if the mills were still operational.

“I believe everything happens within a matrix in the temporal space and therefore this is a crowded book,” Chitrodia, who described herself as “pathologically optimistic”, explained.

“We are products of our times and surrounds and not just our families and core circles. The spotlight, likewise, keeps shifting from one character to another, one locality to another, one time zone to another. Everything around us impacts us, the people we just brush past against even, every minute happenstance, every major disruption. What can follow disruption need not conform to the median and at the same time not be fringe either. It can just be new (that is till it gets less new). What can follow disruption is what this book postulates,” she added.

Chitrodia has observed Mumbai from the 1970s. How does she view the changes that have taken place? How valid is the “Aamchee Mumbai” concept today? How does she see the regeneration of the city – the expansion of the suburbs, the redevelopment of areas like Lalbaugh et al?

“I was born in the ’70s and frankly was busy climbing trees, playing bad cricket and chasing clouds left behind by the mosquito-fumigation man to have observed much of the city then.

“As a grown woman who travels alone by public transport today at odd hours, say, 3 or 4 in the morning, I can say it is still a city where I ‘can’ travel at odd hours. Isn’t that the biggest plus anywhere in the world? Even in this day and age? The taxis and autorickshaws have meters that work too. Another major plus.

“I have friends across the spectrum of region and religion and professions and few have asked me about my caste here.

“During the deluge of 2005, on my way home, I walked through slums where I was offered Glucose biscuits and water. That’s Aamchee Mumbai for us Mumbaikars. It is still a golden city with golden sunsets.

“The squalour is much less now, especially due to the pandemic. Public toilets are sanitised multiple times a day. Mahim Creek, infamous for its stench, does not smell as bad.

The city’s suburbs, Chitrodia said, have come into their own. The upcoming metro will be a further equaliser and ease the rush on the roads and the suburban local trains to the southern parts of Mumbai from the northern and eastern for work. Already decentralisation from the south of the city has happened. Business districts have spread out northwards to Bandra, Andheri, Malad and, of course, the former mill lands of central Mumbai. Likewise, cultural spaces and even malls have sprung up in the suburbs. “I also see breathtaking beautification in the form of murals and landscaping happening on random walls and under flyovers.”

“Certain parts of south Mumbai have largely become heritage crawls that go quiet in the evenings. The suburbs by contrast come alive after dark.

“Lalbaug, like the other areas where mill lands stood such as Parel and Sewri, have moved on from the shock of 1982. A large chunk of the young granddaughters of mill workers are doing well professionally in the corporate world. A local told me women who work in the offices in the redeveloped mill spaces visit local dive bars and no one bothers them. The artistic and liberal vibe of the area–the workers would draw majestic, larger-than-life rangolis on the road, would watch and sometimes act in plays on holidays, sing during community functions, sway to dance performances–has persisted. Many of their grandchildren, especially young men, are employed as visual designers, makeup artists, editors, choreographers, dubbing technicians, and stage managers in movies and theatres.

“Some older men run mobile food stalls, work as salesmen, do odd jobs. Quite a few older women provide dabba service to corporate offices around. And many work as house help and men wash cars in the towers that have sprung up in the locality. Redevelopment of the vast tracts of mill lands had triggered a real estate boom in the city. Many of the mill workers’ children are still waiting for their homes though,” Chitrodia concluded. (IANS)