BY VIKAS DATTA

Is evil a cosmic constant, or a human construct? The answer may not be easy to find and hinge on the intensity of religious belief. But, there is no doubt in accepting that evil, regardless of its origin, has to be countered when it harms people — and that is true in life as well as in literature.

The task of identifying the source of evil may not be easy. Especially when it is important to ascertain that the paranormal is not being adopted to conceal some plainly human criminal activity — as readers of Enid Blyton’s mystery series like the Five Find-Outers and TV series ‘Scooby-Doo’ can attest to.

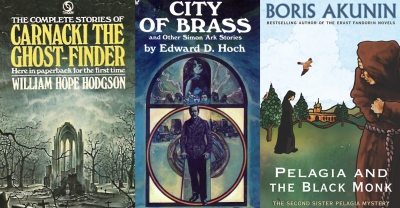

That is the ambiguous, yet not uncommon, situation Thomas Carnacki ‘the Ghost-Finder’, Father Brown, Simon Ark, Sister Pelagia — a special breed of detectives from across the annals of literature for over a century now — often find themselves in.

In fiction, mainstream detectives tackling human evil are ubiquitous, from Sherlock Holmes onwards, but “occult detectives”, who take on seemingly unworldly/other-worldly manifestations of evil, are fewer and lesser-known, despite the sub-genre combining two unique human fixations — mysteries and the supernatural.

Part of this owes to the stipulations set by leading detective fiction writers, as the genre was coming into its own in the early 20th century, to stick to the natural world and its happenings — even in crimes, such as locked room murders, which seemed miraculous.

The second of Ronald Knox’s 10 Commandments of Detective Fiction held that “All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course” and the third of Raymond Chandler’s Ten Commandments said that the mystery “must be realistic in character, setting and atmosphere. It must be about real people in a real world”.

Even Holmes, whose some cases seem supernaturally tinged — ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’, for one, was dismissive about the supernatural and once observed: “The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply.”

The rule did not seem to be followed much. Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ (1841) is held as first instances of detective fiction, but by 1855, Irish-American writer Fitz James O’Brien had his supernatural expert Harry Escott investigate a ghostly being in ‘The Pot of Tulips’ and an invisible one in ‘What Was It? A Mystery’ (1859).

Then, well before Holmes appeared, some stories in Sheridan Le Fanu’s ‘In a Glass Darkly’ (1870) are supernatural cases dealt by physician Dr Martin Hesselius.

There was no shortage of occult detectives from the closing decades of the 19th century — the (mother-son) author pair of E. and H. Heron’s Flaxman Low, Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence, Alice and Claude Askew’s Aylmer Vance, and so on — but it was William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki who broke new ground.

Appearing in only six short stories published between 1910 and 1912, and a further three found and published in 1947 — nearly three decades after the author’s death in the closing days of World War I, Carnacki investigated seemingly supernatural occurrences across Britain, both in stately country houses and in more modest dwellings in the cities.

He relied on his knowledge gleaned from the (fictional) ancient ‘Sigsand Manuscript’, including of the “Saamaa ritual”, and his Electric Pentacle — a modern version of medieval-era protective wands, fashioned out of electrical equipment and neon lighting, where he usually slipped in a camera and a pistol.

For, unlike others of his ilk, his cases are a mix of genuine hauntings and hoaxes — usually with a criminal objective, and at least one, which is both of them.

Carnacki went to achieve an immortality of sorts as successive authors featured him in their versions of his further adventures, including a few where he stars along Holmes, down till 2016.

On the other hand, G.K. Chesterton’s short and stumpy Father Brown, with “a face as round and dull as a Norfolk dumpling”, and “eyes as empty as the North Sea” beneath his large spectacles, seems an unlikely detective.

Unlike the deductive and abductive Holmes, who reasons from premises towards a logical conclusion, aided by his sharp observation and incisive brain sifting through available evidence, this Roman Catholic priest is intuitive, seeking to place himself in the criminal’s mind to find how the deed was done and thus ascertain the perpetrator.

But there are similarities too. Both had keen insights into evil — Holmes, by dint of research, and Father Brown by his work, once telling an adversary: “Has it never struck you that a man, who does next to nothing but hear men’s real sins is not likely to be wholly unaware of human evil?”

And he, like the Baker Street sleuth, scorned supernatural causes, and upheld the cause of reason. Brown once quietly told a criminal how he found the latter was a fraudulent priest: “You attacked reason. That is bad theology.”

His 50-odd stories, which were published in five collections: ‘The Innocence/Wisdom/ Incredulity/Secret/Scandal of Father Brown” between 1911 and 1935 — and three stories found and published posthumously — feature ingenious puzzles/plots, evocative descriptions of time and place, and sometimes, a spell-binding supernatural ambience. These are soon dissipated to stump us with an unexpected, but perfectly reasonable, solution.

Brown’s spirit lives on Sister Pelagia, the second series by Russian-Georgian writer Boris Akunin available in English, about the physically clumsy but mentally agile Orthodox nun in turn-of-century Russia who is tasked by her Bishop to solve serious mysteries.

In her second outing, “Pelagia and the Black Monk” (2007), she is sent to resolve some mysterious, ostensibly paranormal, happenings in a remote island monastery after three men sent by the Bishop meet dire fates (two left mentally unhinged and one dead).

A more worthy successor to Carnacki and Brown, though, is Edward D. Hoch’s Simon Ark, who seems to be an ordinary man in his 60s but claims he is actually an over 2,000-year-old Coptic priest who travels the world to confront evil, specifically Satan.

Some accounts describe him as cursed with immortality for not letting the cross-carrying Jesus rest. The origin of the Wandering Jew’s story does not seem credible since the Coptic Church only came up well after Christ’s crucifixion. The alternative, mentioned in one of his stories, that he once fabricated a Gospel that was so pious that God could not decide whether to reward him with heaven or punish him with hell, seems more proper.

His immortality, however, does not confer him any special powers, save a prodigious amount of knowledge, and only incidental to the accounts. He does have a persuasive way of dealing with the clergy and the police.

Ark debuted in ‘The Village of the Damned’ (1955), where he investigates the horrific incident of 70-odd residents of a remote village committing mass suicide on the instigation of a charismatic cult leader.

This, the first published story of Hoch, who went on to write several novels but is known better for his 950 stories covering 14 different characters, from British cipher expert Jeffrey Rand to professional thief Nick Velvet, to retired New England doctor and “impossible crime” solver Sam Hawthorne.

Out of these, 40-odd feature Ark and can be found in ‘City of Brass and Other Simon Ark Stories’ (1971),

‘The Judges of Hades’ (1971), ‘The Quests of Simon Ark’ (1984), and ‘Funeral in the Fog’ (2020).

All, narrated by an unnamed journalist-turned-publisher who encounters Ark in his first appearance, see Ark solving a string of mysterious or inexplicable crimes that appear to be supernatural, but usually have more prosaic causes — usually one of the seven deadly sins, especially lust, and human agency. Most are set across the US and the UK, though one takes Ark and the narrator down to Madagascar.

Is Ark what he claims? The narrator believes Ark is just trying to seem mysterious, but does admit that he has not visibly aged in all the years he knew him. To this question, Hoch only offers an enigmatic “Perhaps”.

Save some of Carnacki, who dates back to a different time, all these intricate and spine-chilling (at times) stories underscore a dire message: the human mind can be more diabolic and fiendish than what mythology and religion can create. (IANS)