Memoir 25: From JNU to Lake George — With Pramod Sinha, A Friendship That Outlived Time

By Upendra Mishra

BOSTON — This week, my plan was to write about my time in Mexico—those whirlwind years as Bureau Chief for United Press International, covering Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. But something else pulled at my heart, something far more personal.

This summer, my family and I packed our tents and sleeping bags and headed once again to Lake George in upstate New York—my favorite camping spot in the world. Why Lake George? Because that is where, 25 years ago, we pitched our first tent and were baptized into the beautiful, chaotic, mosquito-bitten world of camping.

But this year felt different. The annual trip was no longer just a getaway—it had become a quiet pilgrimage.

As I packed the car and prepared to leave for Lake George, I sat in the driver’s seat for a long moment, staring through the windshield. The keys were with me, but I couldn’t bring myself to start the engine. The thought of returning to that familiar place—without Pramod—felt like opening a door to a room now filled with shadows. For a few moments, I almost didn’t want to go.

But I did.

And as the wheels rolled over the highway and the miles slipped by, something in me began to shift. The grief that had sat so heavy on my chest slowly gave way to memories—real, vivid ones. I could see Pramod standing at the edge of the lake, animatedly showing us how to pitch a tent, his voice rising above the breeze. I remembered how excited the kids were their first time sleeping outdoors, and how he made them laugh with his silly ghost stories around the fire.

And gradually, I began to smile.

Because I realized something important: Pramod hadn’t just introduced us to camping. He had introduced us to something far greater—a way to make memories as a family. That was his true gift. It wasn’t the tents or the guitars or even the music—it was friendship. Deep, joyful, unwavering friendship. The kind that doesn’t end, even when a life does.

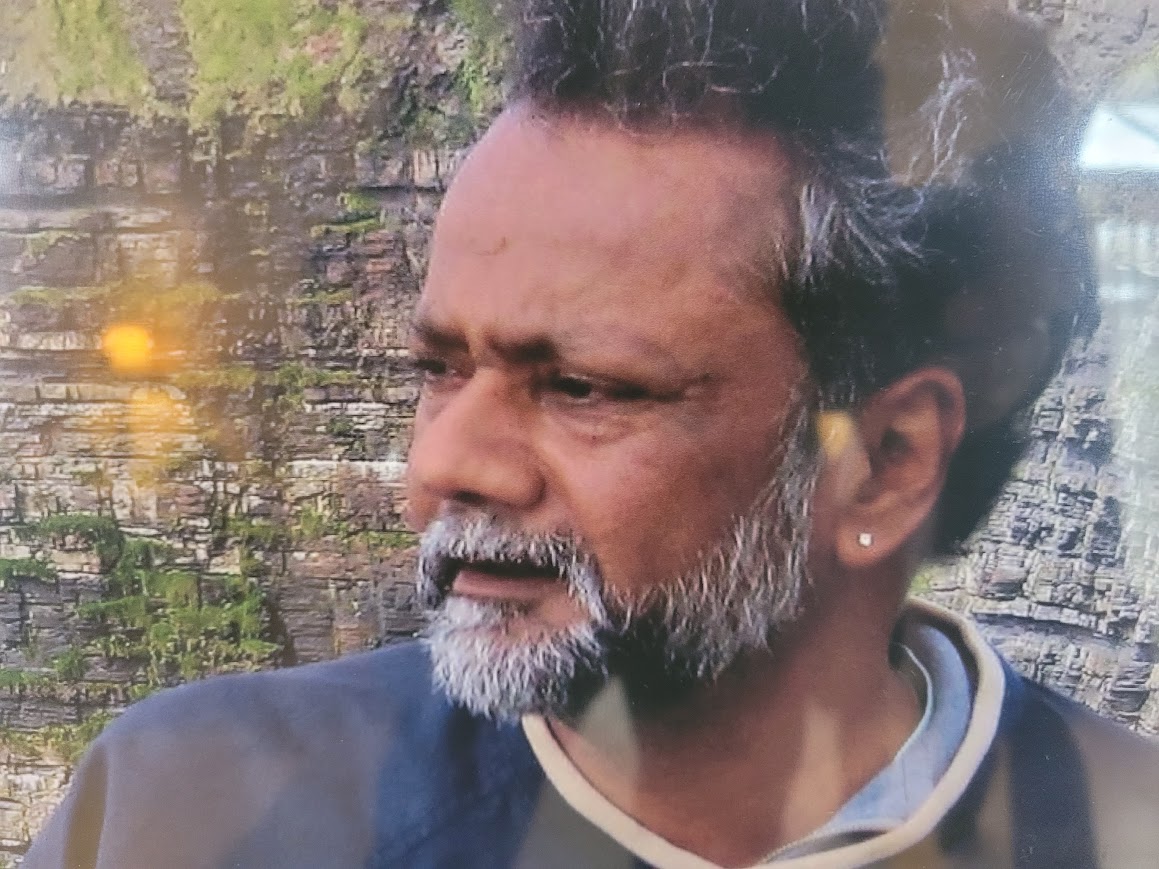

It was Pramod Sinha—my dear friend from JNU—who introduced us to it all. This year, he wasn’t with us. He passed away in December last year, leaving behind a silence too loud to ignore. The kids said, “Let’s go back to Lake George, in his honor.” I agreed, though my heart felt heavier than our fully packed SUV.

As we drove through the winding roads of upstate New York, past sun-dappled trees and roadside diners, memories of Pramod flooded in. I first met him in 1980, in the Kaveri Hostel at JNU. Our rooms were side by side, and from the very beginning, we clicked. We came from similar backgrounds, spoke the same dialect, and shared a curiosity about the world. But Pramod—Pramod was different.

He had a record player.

In those days, that was like owning a spaceship. He played English music—Simon & Garfunkel, The Beatles, and even children’s records like London Bridge Is Falling Down. The tune would drift down the hostel corridor like an unexpected breeze. He had a guitar, could play any Indian instrument, and hummed as easily as he breathed. You knew Pramod was nearby by the music—and the laughter. He was always laughing, and he made you laugh too, whether you wanted to or not.

He was expressive in a way most people at JNU weren’t. He didn’t care for political correctness or ideological puritanism. If something was on his mind, it came out of his mouth in seconds. Many didn’t know what to make of him. I loved it.

I became a lifelong fan of Pramod—and not just because of his music or wit. It was during a very low point that he truly etched himself into my soul.

I had run for the post of Vice President of the JNU Students’ Union. Early predictions had me as a front-runner. I campaigned hard. I believed. And then—I lost. By just 35 votes. At JNU, that was like falling from a cliff.

I was devastated.

I locked myself in my room and refused to speak to anyone. For a week, I didn’t step out. The mess food would be dropped at my door. I would quietly pull in the plate and later slide it back out. I sat in darkness, replaying my defeat, the whispers in the corridors, the humiliation I imagined was written on every face.

People knocked. I didn’t open the door.

Then, Pramod came.

He knocked. Then he knocked again.

“Open the door, yaar,” he said. “I’m not leaving.”

I didn’t respond.

He sat outside my door for I don’t know how long. And then I heard his voice again—so calm, so irritatingly cheerful.

“Congratulations, Upendra!” he said.

I opened the door—angry, confused.

“For what?” I asked.

He barged in and gave me the kind of hug that makes you break inside.

“For winning the election, of course!” he grinned.

“I lost.”

“No, no. You won all the girls’ votes. And trust me, that’s the real victory. Who cares about a few votes here and there? You won where it matters.”

And just like that, the dark fog lifted. I laughed—for the first time in a week. We walked to the Godavari chai dhaba and had endless cups of chai. One by one, other friends joined. Life resumed.

Years passed.

I received a scholarship from the Indian Ministry of Education and moved to Mexico to begin my journalism career. I lost touch with most of my JNU friends. It was the 1980s—phone calls were a luxury, and letters were few and far between. But Pramod never left my thoughts. I often wondered where life had taken him.

Then, one day in 1999, everything changed.

My old friend and fellow Free Thinker from JNU, Chandrashekhar Tibrewal, was visiting us in Massachusetts. As he packed his bags to return to New Jersey, he casually said, “Did you know Pramod Sinha is in the U.S. too?”

I was stunned. “What? Where?”

“Pennsylvania, I think. I’ll send you his number when I get back.”

As soon as he left, I couldn’t wait. I picked up the phone, dialed 411, and asked for any listing under “Pramod Sinha” in Pennsylvania.

There was only one.

I called. A young voice answered. “Hello?”

“Hi. Is Pramod there?”

“He’s mowing the lawn,” said the boy. “Can I take a message?”

“Just tell him… Upendra Mishra from Boston is on the line.”

The background hum of the lawnmower stopped. Then I heard his voice—unchanged.

“UPENDRA!!!” he shouted. “Is it really you?”

That conversation lasted two hours and covered fifteen years. He promised to visit. The very next night, Pramod, Prabha, and their son Pratyush were at our home in Weston. The years melted away.

From that day on, we were inseparable again. We camped together every year—our kids growing up side by side. And it all began at Lake George.

This summer, I sat alone at the campsite.

I visited the exact spot where Pramod used to pitch his tent. I walked the trails we used to hike, drank at the bars where we laughed ourselves silly. At one place, I sat at our table. The other chair—his chair—was empty. But somehow, it wasn’t. I saw him in every tree, in the crackle of the campfire, in the splash of the lake.

His beard. His smile. His singing. His terrible jokes.

He was everywhere.

And in that moment, I finally understood what Rajesh Khanna meant in the movie Anand:

“Anand mara nahi, Anand marte nahi.”

(Anand didn’t die. Anand never dies.)

And again—

“Babumoshai, zindagi badi honi chahiye, lambi nahin.”

(Life should be big, not long.)

Pramod’s life was big—bigger than most. And in some magical way, he still camps with us, and will camp with us every summer.

Only now, his tent is made of memory.

Stay tuned for Chapter 26: Settling in Mexico as a Couple and a Crisis at UPI.

(Upendra Mishra is the author of After the Fall: How Owen Lost Everything and Found What Really Matters, and Precise Marketing: The Proven System for Growing Revenue in a Noisy World and the managing partner of The Mishra Group. He writes passionately about marketing, scriptures, and gardening. Learn more atwww.UpendraMishra.com.)