By Sangeeta Pradhan

INDIA New England Columnist

Do your gut bacteria really determine if you might gain or lose weight? Or end up with a host of other disorders? Read on to find out…

Listening to your gut: Turns out this innocent and somewhat innocuous phrase is loaded, having a much deeper significance than previously thought, as our gut with it’s imperceptible microbial community emerges as the latest and most exciting frontier in medicine today! The scientific community is just beginning to recognize the indispensable role that our gut microbial community (microbiome), plays in supporting health. When this vital community is disrupted, as often happens in our modern environment of manufactured foods, it can lead to inflammation, and associated disorders such as diabetes, obesity, allergies, autoimmune diseases and cancer.

I have always been a big fan of whole foods as they are a major source of fiber to say the least, but emerging evidence on fiber’s role in nourishing the microbiome lends even greater credence to this sometimes neglected food component.

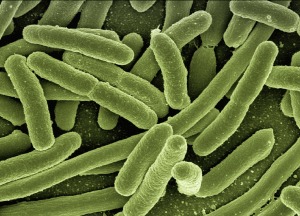

What is the microbiome? The complete genetic content of all the microorganisms that inhabit a site on or in the human body such as your digestive tract, also called the gastro-intestinal or GI tract is referred to as the microbiome. Since time immemorial, human beings have evolved and co-existed with this microbial world. This diverse variety of our microbial inhabitants forms a virtual ecosystem, which as it turns out needs to be sustained and kept in balance much like the earth’s to optimize health.

Only 10% human??: What is mind-boggling to note is that our invisible companions outnumber our own cells 10 to 1, so that makes us only 10% human!!! (Hmm…that might explain a few things about some people who I always wondered about…and myself…!!). Also, the collective genome (entire genetic make up), of our microbial companions contains 100 times as many genes as our own genome, thus underscoring the startling fact that we are a mix of both human and microbial traits. How about that?!!

Our microbial cells outnumber us 10:1. Their collective genes contain 100x as many genes as our own genome.

A give and take with our microbial friends, called symbiosis: We have known all along that many of the members of the microbial community that we harbor share a “symbiotic” relationship with us, helping us digest nutrients that the stomach and small intestine cannot, and synthesize vitamins such as B12 and K . In turn, we provide these tiny tenants with a warm home to grow and thrive. This mutually beneficial relationship is called symbiosis. Emerging evidence has unearthed stunning links between this microbiome and it’s ability to impact it’s host’s (our) immune system and inflammatory response. Many experts refer to our gut as the largest immune organ in the body, housing a microbiome that evolves with us, literally starting with the journey down the birth canal, and continuing to evolve over one’s lifespan.

Invisible ecosystem: This invisible ecosystem ideally should be in a state of harmony where the friendly bacteria predominate, ruling the roost, outnumbering and co-existing with the not-so-friendly bacteria. However, our environment, stress, antibiotics and most notably diet may tip this equilibrium leading to unfavorable shifts in the make up of this microbiome called “dysbiosis“. The typical “Western” diet high in fat and sugar has been linked with dysbiosis. Dysbiosis can potentially trigger inflammation and chronic diseases, that may range the gamut from altered brain functioning, and depression, to obesity, diabetes, allergies, inflammatory bowel disease , irritable bowel syndrome and cancer.

How do your eating habits alter what bugs you harbor? A recent study conducted in humans revealed the dynamic and highly adaptable nature of one’s microbiome to diet. The study demonstrated not just a change in the number of the diverse species of bacteria but also in the kinds of genes they were expressing in response to diet. The study was small consisting of only 10 participants, but what stunned the researchers was how incredibly fast (within 3-4 days), the critters in our gut can respond to dietary changes. From an evolutionary stand point it made sense as prehistoric man may have had to adapt in times of food scarcity, from eating freshly caught prey one week, to gathering nuts and berries the next, when there were no prey to hunt.

Your genes may load the gun, but your environment pulls the trigger: Although it is a normal function of the intestine to allow nutrients to pass through the gut, it also maintains an important barrier function to keep potentially harmful substances from leaving the gut and migrating to the body. In a study assessing the relative contributions of host genes vs diet, a type of bacteria that are known to help protect this intestinal barrier called Bifidobacteria, were virtually absent in mice fed a diet high in fat, independent of their genetic make up. Thus, dietary changes play a predominant role in shaping our microbiota, accounting for an impressive 57% of the variation, whereas genetics accounted for no more than 12%.

Not so complex to understand: While complex carbohydrates increase levels of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium, refined sugars enable the growth of opportunists such as Clostridium difficile. No surprises there!

The typical Western diet high in fat and animal proteins has been linked with altered microbiota. Copyright, Oct 2015, Sangeeta Pradhan, RD, LDN, CDE.

Meat based vs plant-based diets: High protein diets that are rich in meat can increase the activity of certain bacterial enzymes that have been linked with colon carcinogenesis or the initiation of cancer. On the flip side, diets high in plant based foods appear to support a healthy ecosystem in our gut with numerous studies highlighting the all important role that fiber plays in maintaining the integrity of your GI tract. Why is that so?

Short Chain fatty acids: For starters, our microbial inhabitants ferment non-digestible fiber to substances called short chain fatty acids (SCFA), such as propionate, acetate and butyrate that help keep the gut healthy and supply fuel to the cells in your colon. These bacteria are able to do so because they have a large array of enzymes that we humans do not encode in our genes. Emerging evidence has linked propionate with decreased food intake as well as cholesterol, creating a window of opportunity for weight and cholesterol management. Moreover, the production of short chain fatty acids decreases the ph of the colon (acidic environments have a lower ph), thus crowding out potential disease-producing invaders that cannot survive in such an environment.

Different strokes for different folks: Our microbial friends also help us extract energy from indigestible fiber. What is intriguing is that those predisposed to obesity may have gut microbiota that are more efficient at extracting energy than their lean counterparts. Studies show that the predominant bacterial species that constitute the microbiome fall in to two bacterial categories (phyla), the Bacteroidetes and the Firmicutes, and that the relative abundance of these two phyla differs among lean and obese mice; in the study, the obese mouse had a higher proportion of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes than the lean mouse. These results were paralleled in obese humans compared to lean. It is postulated that Firmicutes extract all energy from food, leading to complete absorption and subsequent weight gain, whereas Bacteroidetes “waste” calories that end up in the stool, with resulting weight loss.

A plant based diet high in fiber, has been linked with the growth of beneficial bacteria. Copyright, Oct 2015, Sangeeta Pradhan, RD, LDN, CDE

Promise for the future: What was remarkable was that researchers were able to demonstrate that colonizing germ-free mice with the intestinal microbiome from obese mice, led to an increased total body fat in the recipient mice, despite a lack of change in diet. This makes the manipulation of the microbiome to treat or prevent obesity an exciting and promising avenue for the future.

Picture of Kefir before fermentation: Kefir is fermented milk made by adding Kefir “grains” (the white glob at the bottom of the container) to milk, and is a potent probiotic. Copyright, Sangeeta Pradhan, RD, LDN, CDE

Are we what our microbiomes eat?!: All of these findings raise an important question: Are we really what we eat or are we “what our microbiome eats”? And if so, what should our microbiomes be eating??! Given this relatively new spotlight on the gut as one of the “latest frontiers in medicine and health”, and the pivotal role that diet plays, it is reasonable to examine how we can manipulate our diets to allow this dynamic ecosystem to not just survive, but thrive and flourish! So stay tuned as we take a close look at how we could tap into the power of prebiotics and probiotics to shape this invisible, but dynamic ecosystem to our advantage, in part II of this post, next month!