By Vishnu Makhijani

New Delhi– This truly is the outcome of a lifetime of devotion to the work of Mirza Ghalib from the time Najeeb Jungs mother recited his poetry to him to the time his daughters helped him with the translation by finding the closest words to do justice to the original.

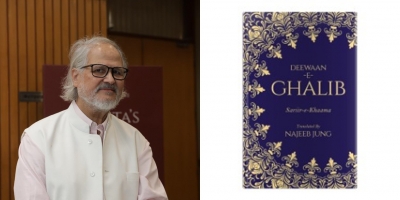

It’s a journey that began when he was four years old but it was only in mid-2010 that the 70-year-old Jung, a former Lieutenant Governor of Delhi and former Vice Chancellor of Jamia Millia Islamia, found the right “Ustad” to guide him through the translation process. The outcome is “DEEWAAN-E-GHALIB � Sariir-e-Khaama” (Rekhta Books), a rendering in English of 235 of Ghalib’s poems along with the originals in the Roman script.

“In these disturbed times, Ghalib’s open discourse, his compassion and understanding, and his plurality assume huge importance. He demolishes routinely held views on man, and his relationship with God, or the existence of heaven or hell, or man’s allurement for heaven and his fear of hell, sin and goodness. For him truth was not the monopoly of any religion or dogma and the path to truth was open to all. To this end he is critical for our times,” Jung told IANS in an interview.

“This is precisely why I have done this translation – a step to bring him closer to those who speak Urdu/Hindustani but their vocabulary is limited, or those who know English and wish to read and understand him. The Roman script needs a bit of practice to familiarise and make reading easy, and the translation gives meaning to the words. I have not provided a commentary to the translations because that would make the book too complex and more of a commentary,” he added.

It’s been quite an inspirational journey and bears telling in its totality.

“As I recall, I was around 4-years-old when my late mother (Ammi) made me learn Ghalib. We also did a bit of Iqbal but Ghalib was her passion. So while my friends in class were reciting English nursery rhymes, I was spouting Ghalib – not that I understood the meanings!! I was a popular child in family gatherings for this. In fact, my mother often told a story how Maulana Azad, who was a family friend and we often visited his home at Edward Road, now renamed the Maulana Azad Road, would insist on listening to Ghalib being recited by a 4/5 year-old child,” Jung said.

As time went by and school (St Columba’s) gained importance, Ghalib receded into the background “but Ammi and I continued reciting once in a while to each other. I kept reading the Deewan (in the original) whenever I could, having acquired many editions and prints over time”.

In early 2000, he was at Oxford as a Visiting Fellow and had access to some outstanding libraries.

“I thought I had read enough and should try my hand at translating the Master for English speaking people or those who understood Urdu but did not have an adequate vocabulary. It did not take any time to realise I was not equipped for the task – neither was my vocabulary so good, nor did I fully comprehend the nuances and depth of his thought. I needed to read much more, and research the various “sharas” (commentaries) by other well know thinkers and writers and therefore to find the right Ustad. The big question was how to get THAT person,” Jung explained.

As luck would have it, he came to the Jamia Millia Islamia in August 2009 and here began his search for the Ustad. His secretary, Zafar Hashmi, introduced him to Prof Khalid Mahmood who, at that time, was the Head of the Urdu department.

“Something clicked” at their first interaction and Jung knew he had found his teacher.

“Khalid sahib is not just an extremely good human being, but a profound thinker. He knew Ghalib, but above all, was happy to read and re-read Ghalib, and spend time with me. Let me add, this was a labour of love by him too – and all the hours and years we worked together, there was never any fee paid or even expected. It was a sacred relationship between a master and pupil on a subject they loved and therefore enjoyed working on together,” Jung said.

From mid-2010 to the end of 2016, every day they read Ghalib; re- read Ghalib, discussed the “ashaar” (nuances of the couplets), looked at commentaries and different interpretations, agreed and at times disagreed.

“By this time I felt ready to attempt a translation. The big question before me whether I should translate the whole Deewan or pick out the popular ghazals, already well known through films and popular ghazals sung by the greats like (K.L.) Saigal, Begum Akhtar, Jagjit Singh etc. and stick to translating them. I do not know why I decided to translate the entire Deewan.

“It has taken me four years to do this. It has been a back-breaking labour of love, a dream I have lived with. Sometimes, a couplet would not be difficult but some would be back-breaking. For instance, I spent months agonising over the first couplet in the Deewan: �Naqsh faryadi hai kiskii shokhi-e-tahreer ka/Kaaghazi hai pairahan har paikar-e-tasweer ka’,” Jung elaborated.

He found it impossible to give true impression to this. So he would wake up at night and think over it, think on it during long walks, during long flights – and never be satisfied.

What eventually emerged was: Against whose playful writings can an image petition/For made of paper is the attire of each image.

There were more like this and hours were spent looking for words that would convey the most appropriate meaning to what Ghalib meant.

“I would seek out my daughters, discuss the couplet and more often than not, they came up with the right expression. It is difficult for a family to be with a husband or parent obsessed with a passion but play along with him with patience and fortitude. In fact for the latter half of 2020, we were all together in New York with everyone contributing to complete the work. I guess every one of us wished to complete this work as soon as possible. Ten years was enough,” Jung said.

He also pointed out that Ghalib is multi-layered and that different meanings can be derived from the same couplet.

“Take the popular couplet: �Aah ko chahiye ik umr asar hone tak/Kaun jiita hai teri zulf ke sar hone tak’. The simplest interpretation is of a lover moaning how long it would take for his sighs to take effect and whether he would even live till the beloved was ready. But could it not be a question to God that how long would a person wait for his prayer to be answered, whether he would not be dead till the prayer was answered?”

“Ghalib has a strange informal relationship with God. He is a Muslim believing in Allah and his Prophet, but rejects dogma and ritualism and opens a world of modern thought and iconoclasm: �Bandagi mein bhi vo aazada o khudbiin hain ke hum/Ulte phir aaye dar-e-Kaaba agar vaa na hua’ (While being a believer, I am so independent and proud/ That I would turn back from the Kaaba were its door not open)

“Or even challenging established Islamic belief: �Hum ko maloom hai jannat ki haqeeqat lekin/Dil ke khush rakhne ko Ghalib ye khayaal achha hai’ (We know the reality of Paradise but/To keep the heart happy, Ghalib, this thought is good),” Jung said.

Has Ghalib received his due in India?

“Well, despite Urdu not being widely read in India, and most people having inadequate vocabularies, Ghalib’s ghazals have been sung manifold by the best in India. While it is near impossible to sing a ghazal in Qawali form, even that has happened. Masterpiece films have been made commencing from the 1940s when Saigal sahib played Ghalib, to Sohrab Modi’s successful film in the early 1950s to the recent TV serial by Gulzar sahib – which will always remain a pure masterpiece bringing Ghalib into our homes,” Jung said.

In 1969, the government celebrated Ghalib’s death centenary with seminars, discussions and even a Mushiara at the Red Fort in Delhi. In addition, the Rekhta Foundation has brought him to the public and vast numbers of non-Urdu speaking people attend these recitations, and talks on him each year.

“So while the poetry may not be understood with its subtleties and nuances, Ghalib is most certainly heard, and admired by millions in India – and with time, his popularity grows,” Jung concluded. (IANS)