By Vikas Datta

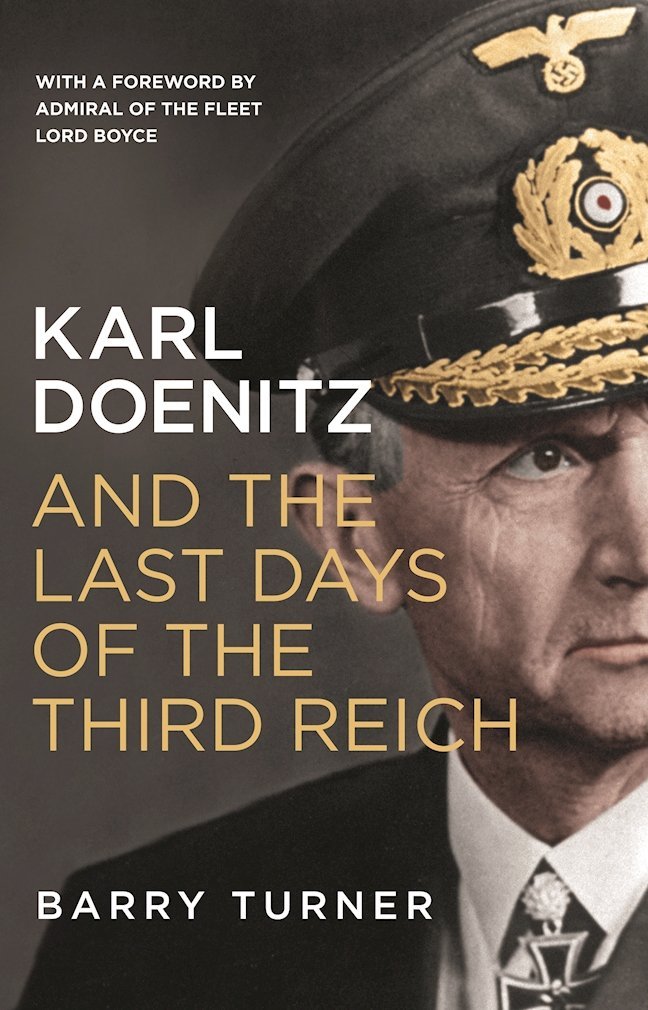

Title: Karl Doenitz and the Last Days of the Third Reich; Author: Barry Turner; Publisher: Icon Books/Penguin India; Pages: 304; Price: Rs 599

Adolf Hitler is so identified with the Nazi epoch that it is commonly thought that his Third Reich began and ended with him. It almost did but in the few days between his suicide and the surrender, Nazi Germany had another Fuehrer, who had been engaged in efforts to save as many of his countrymen from a vengeful enemy in the war’s last few months, and more so when he held power briefly.

But over 70 years after the war, why should this man’s story interest us? For one, due to its balanced account of how the Second World War was a more close thing than realised, and in the immense human suffering it saw, there was a German leader whose intention was ameliorate it – unlike his predecessor.

Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz, the commander-in-chief of the Navy, was an unexpected choice to succeed Hitler, over any top Nazi Party leader or a high officer of the army. He is also not known like other top military figures like Field Marshals Erwin Rommel, Erich von Manstein, Gerd von Rundstedt or General Heinz Guderian, despite his service (and its specific branch – submarines – which he headed for most of the war) coming close to defeating the Allies, by strangling its supply lines.

But what he actually did in the war, why he was chosen as the head of state, and what he did is a story that is not much known, and historian Barry Turner tells with flair.

Turner, who terms Doenitz a “deeply enigmatic figure” among all the military leaders in the war, tries to set his record straight (though never glossing over negative facets), and in doing so, give a sense of the confused situation in the war’s last months.

Starting from the scene in Hitler’s bunker in a battered Berlin, where the dictator and his newly-wedded wife Eva Braun have just committed suicide, the author gives a terse account of the tense developments in that desperate April 1945 which led to candidates like Hermann Goering, Heinrich Himmler, and others being passed over.

Turner then sketches Doenitz’s life and career right from his joining the Imperial German Navy as a cadet in 1910 (aged 18) to the Second World War. Also included are the strategic discussions and debates that ensued in the run-up (where Turner observes then commander-in-chief Erich Raeder, who otherwise admired his subordinate and helped him quite a lot, “could never quite make the leap in strategic imagination that was second nature to Doenitz”) and once it was on, a balanced account of what his U-Boats accomplished.

But the book really picks up pace as Turner comes to the reverses that Nazi Germany faced as the western Allies successfully returned to the European mainland and in the east, the Soviet steamroller gained pace – which in particular, meant much trouble for civilians in their path.

It was then Doenitz convinced Hitler to agree to an evacuation and Operation Hannibal began. Ever bigger than Dunkirk, this, since its beginning in January 1945 to its end, brought out nearly two million civillians and soldiers across the Baltic, and the story is told here in all its shades of heroism, courage, cowardice and desperation.

Equally compelling is the story of how he, as the new chief of the country, tried to do the same during the negotiations for surrender, trying to save as many soldiers and civillians from the Soviets – though the Allies soon divined his objective and ended it with the Soviets getting suspicious of collusion.

It then recounts his fledgling government’s dissolution, his arrest as a war criminal and trial, imprisonment and life after release, when he chose to maintain a low profile.

After his death on December 24, 1980 (being one of the longest-surviving German leaders from the War), the mourners at his funeral included officers of the German – and the British Navy, both of whom ignored instructions not to wear uniforms.

As British Admiral of the Fleet Lord Boyce (First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff 1998-2001, Chief of the Defence Staff 2001-2003), observes in his introduction that the author produces enough evidence for the reader to decide if Doenitz played his role in the war “fairly” – it is not a conclusion that will prove hard to reach.