New Delh–The history of 19th-century India, as reflected in British parliamentary records and colonial accounts, reveals a stark contradiction between imperial rhetoric and lived reality. While the British East India Company (EIC) claimed to rule India for the “welfare and happiness” of its people, debates in London exposed a far grimmer truth — one of crushing debt, curtailed freedoms and an imperial relationship in which Indians were ruled as subjects of despotism rather than partners in governance.

This contradiction found its most revealing expression in the Pindari War of 1817–1819, a conflict publicly justified as an act of “self-defence” but which, from an Indian perspective, marked the decisive phase of Britain’s final conquest of the subcontinent. In Parliament, the war was defended by then President of the Board of Control, George Canning, as a response to the “aggressions of the Pindarries.” Yet, in the same debates, Canning acknowledged what critics saw as the core truth of British policy — the “irrepressible tendency to expansion” of the Indian empire, where the choice lay between conquest and extinction.

For Indians, this doctrine was not an abstract principle but a calculated strategy. The war, they argue, was imposed upon India and funded by Indian revenues, ensuring that the cost of imperial ambition was borne by the colonised.

Debt-Driven Expansion

By the early 19th century, the EIC had transformed from a trading body into a sovereign power wielding military and administrative authority. Yet, it remained financially fragile. Indian revenues were largely consumed by the cost of governance and warfare, while the Company’s debt ballooned from nearly £7 million in 1793 to about £26 million by 1813.

Trade profits, far from easing this burden, were absorbed by the expenses of territorial expansion. As critics noted, conquest became essential not for security alone, but for the Company’s economic survival. New territories were required to pay for old wars, creating a cycle in which India financed its own subjugation.

The Pindari Threat and Imperial Pretext

The Pindaries, described by British officials as marauders without recognised political authority, carried out brutal raids marked by plunder, violence and terror. Accounts of villages devastated and civilians tortured or driven to mass suicide shocked even contemporary observers. A major incursion into Madras territory in 1816 ultimately compelled the British government to act.

However, Indian historians argue that while the atrocities were real, the campaign against the Pindaries served as a convenient pretext. British officials themselves recognised that eliminating the Pindaries risked provoking the powerful Maratha states. The war was thus designed not merely to suppress banditry, but to dismantle the remaining indigenous military powers capable of resisting British dominance.

The Fall of Indigenous Sovereignty

The Pindari War inevitably drew the British into direct conflict with the Maratha chiefs, whose autonomy had already been eroded by the subsidiary alliance system. Though nominally independent, rulers such as the Peshwa wielded little real authority — a condition described in Parliament as “the mockery of independence.”

The resulting uprisings by the Peshwa and other Maratha leaders were portrayed as acts of treachery, but critics saw them as desperate responses to political suffocation. British victories swiftly destroyed Maratha military power, and within months, the Pindaries themselves ceased to exist as a force. The outcome was the near-total consolidation of British control over India.

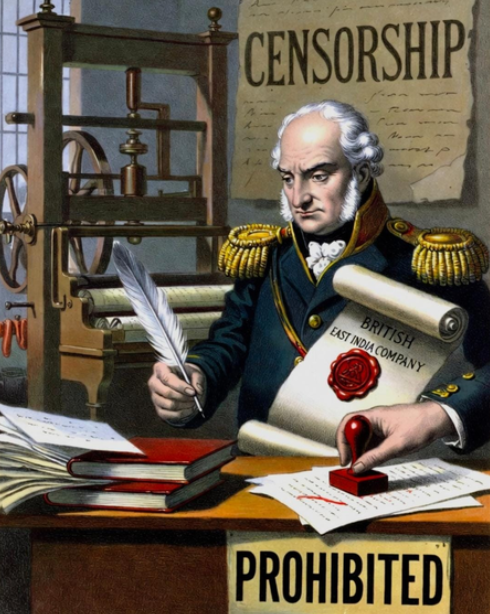

Selective Justice and Silenced Voices

British claims of fighting for justice and national honour were undermined by incidents such as the execution of the Killedar of Talnier fort, who was put to death after surrendering. The act sparked outrage in Parliament, where critics argued it violated European norms of warfare and justice. Yet, accountability was never clearly enforced, reinforcing perceptions of a double standard.

At the same time, the colonial administration tightly controlled the Indian press, fearing that open discussion would expose the fragile legitimacy of British rule. Critics warned that such censorship was essential to a government “founded upon blood and supported by injustice.”

Economic Exploitation

Parallel to territorial expansion was the systematic exploitation of India’s economy. The EIC’s trade monopoly restricted Indian commerce, while resources such as timber and shipbuilding potential were curtailed to protect British industries. Indian wealth fuelled Britain’s industrial rise, even as poverty deepened across the subcontinent.

A Conquest Justified as Necessity

Canning’s admission of an “irrepressible tendency to expansion” stands today as a moment of imperial candour. For Indian observers, it confirmed that wars like the Pindari campaign were not accidental but inevitable outcomes of a system driven by debt, exploitation and the pursuit of absolute control.

The Pindari War ended banditry, but it also extinguished India’s last major independent polities. What followed was an empire sustained by selective justice, silenced dissent and an economy reshaped to serve foreign needs — a conquest achieved not in the name of morality, but of imperial necessity. (Source: IANS)