By Rhea Colaco

First, the good news: 37 babies died for every 1,000 that were born in 2015, two better than the government’s projections of an infant mortality rate (IMR) of 39 for that year in India, according to new data released last week. That’s a drop of 53 per cent over 25 years.

Now, the bad news: The target for IMR reduction was 67 per cent; it has fallen 10 short of the target 27 that India agreed to under the 2015 millennium development goals (MDGs), set in consultation with the United Nations. India has also not achieved the IMR target of 30 that the government itself set for 2012.

To get an idea of India’s global standing, compare its 2015 IMR average of 37 with IMRs of 35 for 154 low- and middle-income nations; five for 26 north American nations and three for 39 nations in the Euro area.

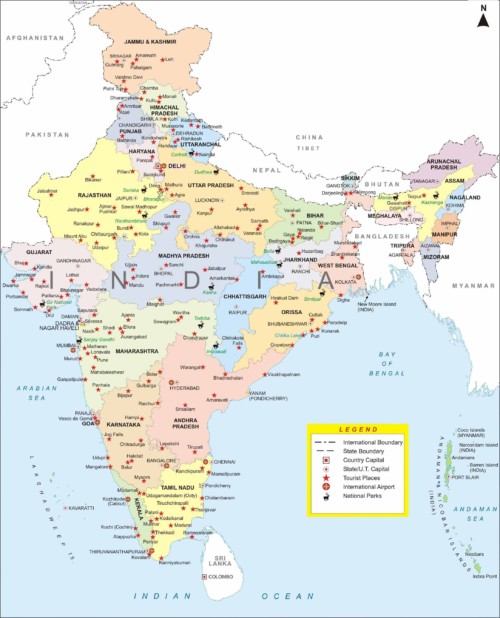

There were wide variations in IMR — a bellwether of national health — across India, according to the latest report from the Sample Registration System (SRS) bulletin, with smaller, more literate states reporting IMRs close to or better than richer countries and larger, poorer states reporting more deaths than poorer countries, indicating the uneven nature of healthcare.

There were wide variations in IMR — a bellwether of national health — across India, according to the latest report from the Sample Registration System (SRS) bulletin, with smaller, more literate states reporting IMRs close to or better than richer countries and larger, poorer states reporting more deaths than poorer countries, indicating the uneven nature of healthcare.

The overall improvement in IMR over a quarter century is likely linked to a variety of government interventions, including institutional deliveries and providing iron and folic-acid tablets to pregnant women, and rising incomes and living circumstances since economic liberalisation in 1991.

Of 36 Indian states and Union territories (UTs), the lowest IMRs were reported from Goa and Manipur with nine infant deaths per 1,000 live births — that is the same as China, Bulgaria and Costa Rica and one better than the consolidated figure for Europe and Central Asia, according to 2015 World Bank data.

In contrast, Madhya Pradesh reported India’s highest IMR with 50 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, or worse than Ethiopia and Ghana and marginally better than disaster-wracked Haiti (52) and unstable Zimbabwe (47), but better than its 2014 rate of 52.

Uttarakhand was the only state that reported a worsening in its IMR, from 33 infant deaths for every 1,000 live births in 2014 to 34 in 2015.

In terms of MDG progress, from the larger states, only Tamil Nadu has met its state MDG target with a reduction of 67 per cent in IMR to reach 19 infant deaths per 1,000 live births in 2015. Sikkim, Manipur and Daman and Diu have all achieved a two-third reduction from their 1991 estimates. Goa, Maharashtra, Puducherry, Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir, Arunachal Pradesh and Odisha have all come very close to achieving their MDG state-specific targets.

While Kerala doesn’t feature on the list — its IMR for 2015 is 12, and well within India’s national MDG target — that is because its IMR for 1990 was as low as 17 to begin with.

Infant girls in India continue to die at a greater rates than infant boys, and there has been almost no reduction in the gap in IMRs, the new data reveal.

Male babies have an IMR of 35 deaths per 1,000 live births, while female babies have an IMR of 39 per 1,000 live births.

The factors that impact the IMR also reflect the well-being of a nation. Environmental and living conditions, rates of illness, health of mothers and their access to quality pre- and post-natal care contribute to infant survival rates.

Just as rural-urban differentials in the IMR are sizeable and significant, so too are the differentials by wealth. In other words, babies born in poorer families tend to die in larger numbers. The poor are the most vulnerable to health disadvantages and the IMR tends to reflect that.

However, these inequities in mortality reflect not just differences in access to health services for both children and mothers but also inadequacies of India’s public health system and its inability to deliver quality and equitable services.

The National Rural Health Mission, launched in 2005, set India’s IMR target as 30 deaths per 1,000 live births by 2012. However, we have still not been able to achieve in 2017 the target set for 2012.

The MDG achievements of 2015 set the base for the 2030 sustainable development goals (SDGs). While infant mortality is not a target the SDGs will monitor, it will monitor neonatal mortality — death during the first 28 days of life — a key component of infant mortality.

Neonatal mortality largely stems from poor maternal health, inadequate antenatal care, improper management of pregnancy complications and delivery-related complications.

In 2013, neonatal mortality contributed to 68 per cent of all infant deaths in India, and it will continue to represent an increasing proportion of child deaths. The prime minister’s Maternity Benefit Scheme — which appears to be a universalisation and expansion of the Indira Gandhi Matritva Sahyog Yojana — could possibly be a step that will better maternal health and delivery outcomes through conditional cash transfers.

If India is to achieve its SDG targets across gender, wealth and caste, it needs more attention directed towards infant and maternal health policies, or 2030 will — once again — see India falling short of its health targets. (IANS)