By Subrata Das

(Editors note: Seattle, WA, became the first US city in the United States last month to ban caste discrimination, pushing back against opposition by several Indian-American organizations. In this Op-Ed article, SETU Director and Co-Founder Subrata Das talks about casting out caste in the “fifth” Veda style through three plays he is directing for SETU.)

BELMONT, MA–The foundation of Bharat Muni’s Natyashastra, a Sanskrit treatise on the performing arts of India which dates back to the 2nd century BC, was non-casteist in nature. As the Vedas (knowledge), the most ancient Hindu scriptures in four parts from around 1500 BC, were not even allowed to listen to by those born as Sudras at that time, Natyashastra (aka the “fifth” Veda) was created to belong to all the Varnas (color-groups, same as caste). In fact, the four pillars of a detailed stage design in Natyashastra were equally attributed to the four castes, which existed during the era, with gold thrown at the feet of the four foundational pillars. The first Natya (drama), which had to be audible and visible, was presented as an object of diversion from sensual pleasure. It was enjoyed by the Gods alongside Demons (i.e., Asuras and Daityas) but after some modifications.

A brief background for those who are not familiar – casteism is an age-old, deep-rooted social issue in Indian society. It encourages the practice of discrimination against people based on their caste, which is divided into four categories in decreasing status – Brahmin, Kshtriya, Vaishya, and Sudra – and the uncategorizable Untouchables. This form of discrimination is seen in every sphere of life, such as in the workplace, in educational spaces, and in social interactions, spilling to other countries with large number of Indian diasporas, including here in the USA. Seattle has become the first city to explicitly ban discrimination on the basis of caste as a step to avoid such discrimination becoming more pervasive in the US.

My theater journey in this country began almost two decades ago, co-founding with Jayanti Bandyopadhyay a group called SETU, with a mission to “bridge” the cultural gap and a hope for a fair and equitable society in the future. We selectively produce plays in English to project the ways of life in India in a global context. SETU portrays India’s social, political and economic scenarios from the past and the present, highlighting both our rich cultural heritage and social malaise. My growing up in a remote Indian village, witnessing some of the extreme social injustices, ranging from untouchability, women disenfranchisement, and Hijra mockery to religious and political violence, certainly influenced my selection and direction of the plays over the years. Those include Tendulkar’s Kamala, Karnad’s The Fire and the Rain, Brook/Carriere’s Mahabharata, Dattani’s Seven Steps around the Fire, and my own Once Upon a Time NOT in Bollywood, just to name a few. Casteism is perhaps one social issue that touched me the most. As casteism is so ubiquitous and often explicit, especially in villages, there is a danger of taking it as part of the lives of people in India and continuing to live with the status quo. The 20th anniversary year of SETU provided me a wonderful opportunity to bring the casteism issue in fore via three strong plays.

My theater journey in this country began almost two decades ago, co-founding with Jayanti Bandyopadhyay a group called SETU, with a mission to “bridge” the cultural gap and a hope for a fair and equitable society in the future. We selectively produce plays in English to project the ways of life in India in a global context. SETU portrays India’s social, political and economic scenarios from the past and the present, highlighting both our rich cultural heritage and social malaise. My growing up in a remote Indian village, witnessing some of the extreme social injustices, ranging from untouchability, women disenfranchisement, and Hijra mockery to religious and political violence, certainly influenced my selection and direction of the plays over the years. Those include Tendulkar’s Kamala, Karnad’s The Fire and the Rain, Brook/Carriere’s Mahabharata, Dattani’s Seven Steps around the Fire, and my own Once Upon a Time NOT in Bollywood, just to name a few. Casteism is perhaps one social issue that touched me the most. As casteism is so ubiquitous and often explicit, especially in villages, there is a danger of taking it as part of the lives of people in India and continuing to live with the status quo. The 20th anniversary year of SETU provided me a wonderful opportunity to bring the casteism issue in fore via three strong plays.

The root of casteism is often attributed to Rig Veda’s Purusha (Hymn 10:90) of around 1500 BC, where the different castes originated from the different parts of the body of Purusha (self). The Brahmins come from the mouth and the Shudras come from the feet. I have my own doubts with this origination theory of caste, given that the Earth was also born from the feet in this same Hymn. Regardless, however way in which we interpret its origin, casteism was already entrenched within the Indian society by the time of Natyashastra, thanks to some abhorrent text of Manu Smriti. The British colonial policy in India, like everywhere else, had always pursued the divide-and-conquer strategy and the Indian caste hierarchy within an already-divided, caste-based society was an added bonus. The British reinforced this history, and thus the oppressed became increasingly oppressed and isolated.

The Indian government officially abolished the practice of casteism in 1950, almost immediately after independence. But the question remaining is whether the reservation policy, which creates a dilemma between a constitutionally illegal caste system and its recognition at the same time to provide benefits, does actually work. The common grievance is that it benefits the wrong people and that more economic benefits for the poorest of India would make better sense instead. Nonetheless, the situation on the ground is changing as I have personally witnessed an evolution in Indian villages. Despite Rig Veda perspective on the origins of people of different castes, that they’re from different parts of the body of Purusha, today’s society is more of a mix. Cricketers, for example, come from all strata of society, enjoying popularity and earning huge sums of money, by exploiting their hands, shoulders, and feet skills. Entrepreneurs do the same with their heads and film stars with their bodies and cognitive skills.

The orthodox community will often argue that if we get rid of the caste system from our society, we will be leaving out an important part of our tradition. I’d like to counter this argument – we uphold plenty of other important traditions to our people and to the rest of the world. This includes, to name a few, our deep and intellectually brilliant philosophy, universally practiced yoga and cuisine, vegetarianism, belief in polytheism but eventual oneness, rich educational materials like Nyaya and Natyashastra, and many more that we should be very proud of. On this last item of the list, I personally have used the idea of logic to simulate human cognitive reasoning in my academic work and the extensive list of thirty different types and the rasas (Sentiments) and the bhavas (States) when directing plays.

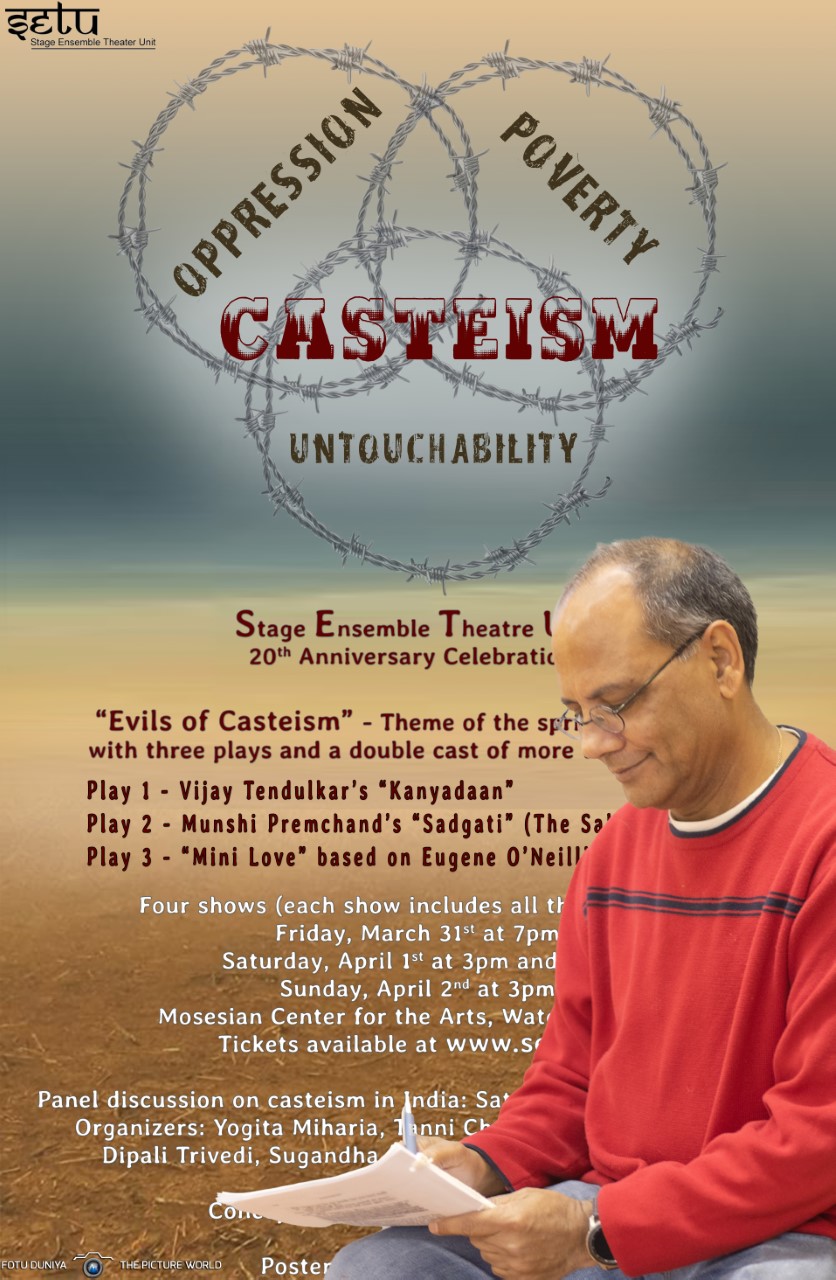

This is important background to better understand SETU’s latest bold venture! Come and see forthcoming Evils of Casteism in three plays with 30 actors as part of SETU’s 20th anniversary celebration.

1) Vijay Tendulkar’s “Kanyadaan”, which roughly translates to “Giving the Daughter Away”, portraying the conflict between an upper-class family and their Dalit son-in-law in 1980’s India.

2) Munshi Premchand’s “Sadgati” (The Salvation), a short play that I scripted based on the translation of TC Ghai, depicting the tragic story of a low-caste village family and a heartless Brahmin couple from 1930’s rural India.

3) “Mini Love”, a short play set in modern India that Nilay Mukherjee and I scripted based on Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie, presenting an uplifting story of love between a prostitute and an upper-class Jat, resulting in a single “united caste of India” in the end.

There will be four showtimes between Mar 31 – April 2 at the Mosesian Center for the Arts, Watertown, MA. All three plays will be performed at each show. Tickets available at www.setu.us. In addition, there will be a panel discussion on the Indian caste system on Saturday, April 1 at 5:30pm. The panel is free for all and will be organized by Yogita Miharia, Tanni Chaudhuri, Priya Samant, Dipali Trivedi, Sugandha Gopal, and Jayanti Bandyopadhyay.

Photo and poster credit: Fotu Duniya (Vasudha Kudrimoti, Krishan Aneja, and Sanjay Kudrimoti)

(Subrata Das is the director and co-founder of SETU (www.setu.us), a Boston based non-profit theater group with a mission to bridge the cultural gap between India and the western society through the medium of theater. Subrata also served as a board member of Central Square Theater, Cambridge, MA.)