By Leah Shafer

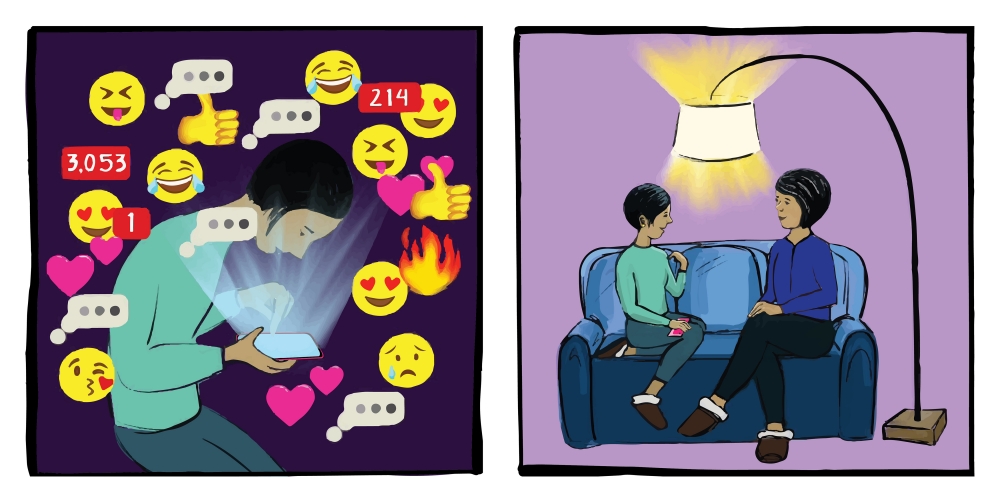

As adults witness the rising tides of teenaged anxiety, it’s tough not to notice a common thread that runs through the epidemic — something that past generations never dealt with. Clutched in the hand of nearly every teen is a smartphone, buzzing and beeping and blinking with social media notifications.

Parents, all too often, just want to grab their teen’s phone and stuff it in a drawer. But is social media and the omnipresence of digital interactions really the cause of all this anxiety?

The short answer is: It’s complicated.

Recent studies have noted a significant uptick in depression and suicidal thoughts over the past several years for teens, especially those who spend multiple hours a day using screens, and especially girls. But many of the pressures teenagers feel from social media are actually consistent with developmentally normal concerns around social standing and self-expression. Social media can certainly exacerbate these anxieties, but for parents to truly help their children cope, they should avoid making a blanket condemnation. Instead, parents should tailor their approach to the individual, learning where a particular child’s stressors lie and how that child can best gain control of this alluring, powerful way to connect with peers.

Many of the pressures teenagers feel from social media are actually consistent with developmentally normal concerns around social standing and self-expression.

Many of the pressures teenagers feel from social media are actually consistent with developmentally normal concerns around social standing and self-expression.

A Link Between Social Media and Mental Health Concerns

Many experts have described a rise in sleeplessness, loneliness, worry, and dependence among teenagers — a rise that coincides with the release of the first iPhone 10 years ago. One study found that 48 percent of teens who spend five hours per day on an electronic device have at least one suicide risk factor, compared to 33 percent of teens who spend two hours a day on an electronic device. We’ve all heard anecdotes, too, of teens being reduced to tears from the constant communication and comparisons that social media invites.

Through likes and follows, teens are “getting actual data on how much people like them and their appearance,” says Lindsey Giller, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute who specializes in youth and young adults with mood disorders. “And you’re not having any break from that technology.” She’s seen teens with anxiety, poor self-esteem, insecurity, and sadness attributed, at least in part, to constant social media use.

Teenage Challenges and Stressors, Exacerbated

But the connection between anxiety and social media might not be simple, or purely negative. Correlation does not equal causation; it may be that depression and anxiety lead to more social media use, for example, rather than the other way around. There could also be an unknown third variable — for instance, academic pressures or economic concerns — connecting them, or teens could simply be more likely to admit to mental health concerns now than they were in previous generations.

It’s also important to remember that teens experience social media in a wide range of ways. The ability to raise awareness, connect with people across the world, and share moments of beauty can be empowering and uplifting for some. And many teens understand that the images they see are curated snapshots, not real-life indicators, and are less likely to let those posts make them feel insecure about their own lives.

Above all, says researcher Emily Weinstein, who studies teens and their social media habits, parents need to keep in mind that it’s probably not just social media that’s making their teens anxious — it’s the normal social stressors that these platforms facilitate, albeit at a different size and scale.

In the same way that different teenagers need different types of social support from their parents, they need different types of digital support, as well. If your teen seems irritable or overwhelmed by social media, pay attention to what specifically is causing those feelings.

“So many of the behaviors we’re talking about have pre-digital corollaries,” says Weinstein, a postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. “They’re the same sort of developmental challenges that adolescents have grappled with for decades, though now they’re taking place in different spaces that can certainly amplify them and shift their quality, quantity, and scale.

“But the idea of wanting to fit in, the critical importance of peer relationships, and the process of figuring out which version of yourself you want to be and how you want to express that identity to others — those features of adolescence are not new.”

What’s Triggering about Social Media?

Youth and technology expert Amanda Lenhart’s 2015 Pew study of teens, technology, and friendships reveals a range of social media-induced stressors:

- Seeing people posting about events to which you haven’t been invited

- Feeling pressure to post positive and attractive content about yourself

- Feeling pressure to get comments and likes on your posts

- Having someone post things about you that you cannot change or control

In analyses of thousands of adolescents’ reactions to digital stressors, Weinstein and her colleagues have found even more challenges:

- Feeling replaceable: If you don’t respond to a best friend’s picture quickly or effusively enough, will she find a better friend?

- Too much communication: A boyfriend or girlfriend wants you to be texting far more often than you’re comfortable with.

- Digital “FOMO”: If you’re not up-to-date on the latest social media posts, will it prevent you from feeling like you can participate in real-life conversations at school the next day?

- Attachment to actual devices: If your phone is out of reach, will your privacy be invaded? Will you miss a message from a friend when he needs you?

For Parents, Strategies on Mitigating Anxiety — Without Overreacting

With so many different stressors, a key piece of advice for parents is to individualize your approach. In the same way that different teenagers need different types of social support from their parents, they need different types of digital support, as well. Weinstein suggests that if your teen seems irritable or overwhelmed by social media, pay attention to what specifically is causing those feelings.

Giller agrees. “Really check in with your teen about what’s going on,” she says. Parents can and should help support and problem-solve with their teen, but they should also offer validation about how difficult these situations can be.

Don’t just take your teen’s phone away if you suspect drama. In most situations, it’s best to work with your teen around social media expectations.

Relatedly, don’t just take your teen’s phone away if you suspect drama. Doing so won’t get to the heart of the social issue at play — and it could potentially make your teen more upset by separating her from her friends and other aspects of digital media she enjoys.

However, as a family, you can also set screen-free times — whether it’s every evening after 9 p.m., on the car ride to school, an occasional screen-free weekend, or longer stretches over vacations and camps. “Many teens say they appreciate” these chances, says education writer Anya Kamenetz, whose upcoming book The Art of Screen Time: How Your Family Can Balance Digital Media and Real Life explores these issues in-depth.

A significant part of your teen’s phone habits may be related to her parents, too. “Be good role models in your own use of tech,” advises Kamenetz. That means being mindful of your own distracted habit of reaching for your cell, but it also means rejecting the isolation that screen time can generate. Make digital media an opportunity for real-life social opportunities, she says. Share some media activities with your teenager — playing games, watching YouTube clips, or reading up on mutual interests together.

And in most situations, it’s best to work with your teen to set social media expectations. “You want to build consensus and get their buy-in,” says Kamenetz. Constant surveillance or control won’t build trust. Make it an open, mutual discussion.

You want to get teens to put their devices down on their own, says Weinstein, “so that you’re helping them build their ability to manage their interactions with and through technology.” And that’s increasingly looking like a key life skill that we’ll all need to develop, now and into the future.

(Published with permission from Harvard Gazette.)