By Vishnu Makhijani

New Delhi– He was the first Tibetan to be admitted a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons but could re-visit his beloved “mystic” homeland only in 2007, four years before he died aged 79, to find it had “withered away not so much from Communist Chinese genocide as from geno-dilution” — or inward mass migration.

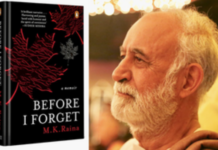

This is the pain that oozes through every page of Tsewang Yishey Pemba’s posthumously published “White Crane, Lend Me Your Wings” (Niyogi Books/Rs 495-$15/868 pp) — a tale of love and war that is also a poignant cry for Tibetan freedom.

“Mystic Tibet has withered away, not so much from Communist Chinese genocide as from geno-dilution by mass migrations of ethnic Han Chinese from the heart of the New China, the Great Motherland. This is obvious everywhere in the streets, offices, restaurants shops and mansions of Lhasa.

“At Lhasa airport, some distance from the city, announcements of Arrivals and Departures are made in Chinese, Tibetan and English. On Arrival, there are no Customs and Immigration formalities, for passports have already been inspected and stamped in Beijing or Chengdu or Xining or Xian (flying south of the legendary Yenan). There are frequent direct flights from Chengdu to Lhasa, flying over Lithang and Nyarong. Is it wildly, childishly, stupidly imaginative to conjecture that occasionally — weather permitting — such aircraft might encounter white cranes still flying from Lhasa towards Lithang (one of the locales in which the book is set)?” the author wonders.

“At Lhasa airport, some distance from the city, announcements of Arrivals and Departures are made in Chinese, Tibetan and English. On Arrival, there are no Customs and Immigration formalities, for passports have already been inspected and stamped in Beijing or Chengdu or Xining or Xian (flying south of the legendary Yenan). There are frequent direct flights from Chengdu to Lhasa, flying over Lithang and Nyarong. Is it wildly, childishly, stupidly imaginative to conjecture that occasionally — weather permitting — such aircraft might encounter white cranes still flying from Lhasa towards Lithang (one of the locales in which the book is set)?” the author wonders.

The title, in fact, is a line from a poem by the Sixth Dalai Lama in which he consoles his followers banished from the Nyarong Valley by the Manchus in 1720.

Thus, it is little wonder that Pemba’s son Riga remembers his father “enter into a deep trance” while boarding the train back from Lhasa to Beijing, renowned Tibetologist and poet Shelly Bhoil writes in the introduction.

“Dr Pemba became unusually quiet for months together after his return from Tibet. Thereafter, he dedicated himself to writing ‘White Crane, Lend Me Your Wings’… Pemba died of liver cancer on November 26, 2011, (three-and-a-half years after returning from Tibet). The publication of this novel, which he wrote relentlessly despite being in physical pain, was his last wish,” Bhoil says.

The novel is set in the first half of the 20th century and Pemba skilfully weaves a dazzling tapestry of individual lives and sweeping events, creating an epic vision of a country and people during a time of tremendous upheaval.

The book begins with a never-before-told story of a failed Christian mission in Tibet and takes the reader into the heartland of Eastern Tibet by capturing the zeitgeist of the fierce warrior tribe of Khampas ruled by chieftains.

The coming-of-age narrative is a riveting tale of vengeance, warfare and love unfolded through the story of two young boys and their families and friends.

The author’s ability to separate emotions and view both sides of a national catastrophe objectively is applaudable. Ultimately, the novel delves into themes such as tradition versus modernity, individual choice and freedom, the nature of governance, the role of religion in people’s lives, the inevitability of change, and the importance of human values such as loyalty and compassion.

Born at Gyantse in Tibet in 1932, Pemba was enrolled by his father, a Tibetan cadre officer in the British Trade agency, at age eight in the Victoria Boys School at Kurseong near Darjeeling.

He was the first Tibetan to become a doctor and surgeon in Western medical science from the University of London in 1955. He was awarded the prestigious Hallet Prize by the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh, in 1966.

He also founded the first hospital in Bhutan in 1956 and was a member of the Bhutanese delegation to the WHO in Geneva in 1989.

In between, there was much pain he had to endure — his parents had perished in the devastating Yarlung Tsangpo floods at Gyantse and Tibet was no longer a de facto independent country.

It would, thus, be only natural for Pemba to pen a masterpiece such as this. (IANS)