By Leah Burrows

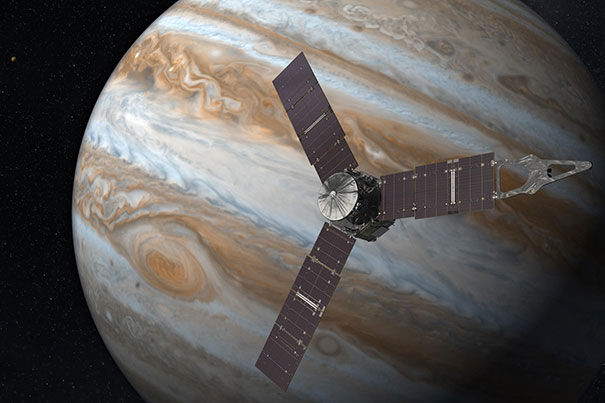

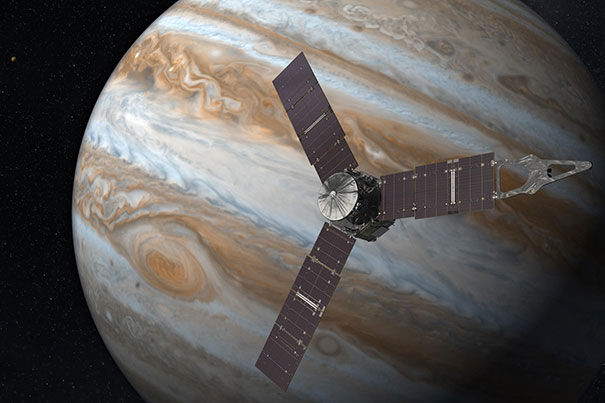

In less than a week, the spacecraft Juno will reach Jupiter, culminating a five-year, billion-dollar journey. Its mission: to orbit and peer deep inside the gas giant and unravel its origin and evolution. One of the biggest mysteries surrounding Jupiter is how it generates its powerful magnetic field, the strongest in the solar system.

One theory is that about halfway to Jupiter’s core, the pressures and temperatures become so intense that the hydrogen that makes up 90 percent of the planet — molecular gas on Earth — loses hold of its electrons and begins behaving like a liquid metal. Oceans of liquid metallic hydrogen surrounding Jupiter’s core would explain its powerful magnetic field.

But how and when does this transition from gas to liquid metal occur? How does it behave? Researchers hope that Juno will shed some light on this exotic state of hydrogen. But one doesn’t need to travel all the way to Jupiter to study it.

Four hundred million miles away, in a small, windowless room in the basement of Lyman Laboratory on Oxford Street in Cambridge, there was, for a fraction of a fraction of a second, a small piece of Jupiter.

Earlier this year, in an experiment about 5 feet long, Harvard University researchers say they observed evidence of the abrupt transition of hydrogen from liquid insulator to liquid metal. It is one of the first times such a transition has ever been observed in any experiment.

They published their research in Physical Review B.

“This is planetary science on the bench,” said Mohamed Zaghoo, the NASA Earth & Space Science Fellow at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). “The question of how hydrogen transitions into a metallic state — whether that is an abrupt transition or not — has huge implications for planetary science. How hydrogen transitions inside Jupiter, for example, says a lot about the evolution, the temperature, and the structure of these gas giants’ interiors.”

In the experiment, Zaghoo, Ashkan Salamat, and senior author Isaac Silvera, the Thomas D. Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences, recreated the extreme pressures and temperatures of Jupiter by squeezing a sample of hydrogen between two diamond tips, about 100 microns wide, and firing short bursts of lasers of increasing intensity to raise the temperature.

This experimental setup is significantly smaller and cheaper than other current techniques to generate metallic hydrogen, most of which rely on huge guns or lasers that generate shock waves to heat and pressurize hydrogen.

The transition of liquid to metallic hydrogen happens too quickly for human eyes to observe, and the sample lasts only a fraction of a second before it deteriorates. So instead of watching the sample itself for evidence of the transition, the team watched lasers pointed at the sample. When the phase transition occurred, the lasers abruptly reflected.

“At some point, the hydrogen abruptly transitioned from an insulating, transparent state, like glass, to a shiny metallic state that reflected light, like copper, gold, or any other metal,” Zaghoo said. “Because this experiment, unlike shock wave experiments, isn’t destructive, we could run the experiment continuously, doing measurements and monitoring for weeks and months to learn about the transition.”

“This is the simplest and most fundamental atomic system, yet modern theory has large variances in predictions for the transition pressure,” Silvera said. “Our observation serves as a crucial guide to modern theory.”

The results represent a culmination of decades of research by the Silvera group. The data collected could begin to answer some of the fundamental questions about the origins of solar systems.

Metallic hydrogen also has important ramifications here on Earth, especially in energy and materials science.

“A lot of people are talking about the hydrogen economy because hydrogen is combustibly clean, and it’s very abundant,” said Zaghoo. “If you can compress hydrogen into high density, it has a lot of energy compacted into it.”

“As a rocket fuel, metallic hydrogen would revolutionize rocketry as propellant, an order of magnitude more powerful than any known chemical,” said Silvera. “This could cut down the time it takes to get to Mars from nine months to about two months, transforming prospects of human space endeavors.”

Metallic hydrogen could be used to make super-conductors at room temperature or even higher.

The Juno mission goes hand-in-hand with laboratory experiments into metallic hydrogen, Zaghoo said.

“The measurements of Jupiter’s magnetic field that Juno will be collecting is directly related to our data,” he said. “We’re not in competition with NASA, but, in some ways, we got to Jupiter first.”

(Reprinted with permission from Harvard Gazette.)