By Monish Gulati

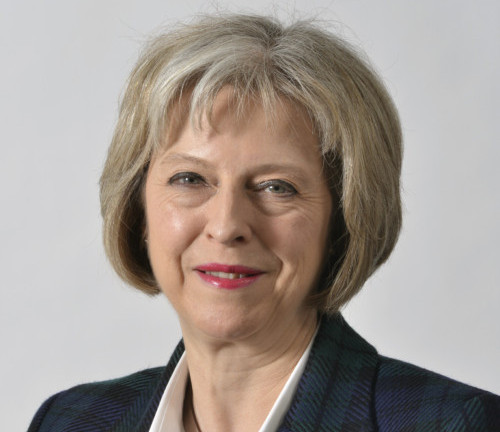

British Prime Minister Theresa May will be in New Delhi from November 6 to 8 on her first bilateral visit outside the European Union (EU). The visit is seen as an opportunity for the two sides to strengthen business-to-business engagement in the areas of technology, finance, entrepreneurship, innovation, design, IPRs, higher education, and defence and security. She will hold talks with Prime Minister Narendra Modi and review all aspects of the India-UK Strategic Partnership. The Joint Economic and Trade Committee (JETCO) meeting will be held on the sidelines of the visit.

May is expected to use the trip to deliver on her ambitious vision for Britain after Brexit by introducing new and emerging enterprises, as well as more established players, to the key Indian market. While announcing the visit, she had said, “We have the chance to forge a new global role for the UK — to look beyond our continent and towards the economic and diplomatic opportunities in the wider world.” The visit is expected to unveil Britain’s post-Brexit “new global role” and where India figures in that.

Among issues likely to be at the forefront of bilateral discussion is a potential India-UK Free Trade Agreement. On trade, May has declared that the UK will become the “most passionate, most consistent, and most convincing advocate for free trade”, and during the current visit she will be focusing on small- and medium-sized businesses and her delegation will include representation from every region of the UK.

During the visit she, along with Modi, will inaugurate the India-UK Tech Summit in New Delhi, jointly hosted by the Confederation of Indian Indutsry (CII) and the Department of Science and Technology. The summit will bring together entrepreneurs, business leaders and policymakers from both sides for a three-day exchange to focus on matters such as technology, education, design, advanced manufacturing and robotics, among others which are seen as critical to India’s developing economy.

However, her trip to India comes on the back of two developments back home: the High Court ruling on Brexit and the announcement of the new visa rules for non-EU nationals. The former has led to a piquant situation where the May government has been shorn off the sovereign right to set into motion the process to withdraw from the EU (by invoking Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty) prior to securing a parliamentary approval. The Conservative government has a small majority in the House of Commons. The government is set to appeal in the Supreme Court. May had earlier declared her intention to initiate Brexit by March 2017 and complete the process in two years.

Even prior to the High Court’s ruling, some critics were claiming that May’s visit is less about India and more about the need to reassure voters back home on her government’s ability to manage post-Brexit concerns, particularly those regarding the economy. Britain cannot legally make any trade deals with India until it is officially out of the EU, which is by 2019 at the earliest; the High Court’s ruling may see the deadline slip even further. Though May has assured that there will be no change in the 2019 deadline, there are already talks about the possibility of a mid-term election on the issue.

The UK government has also announced changes to its visa policy for non-EU nationals, which will affect a large number of Indians, especially IT professionals. Under the new visa rules announced this week by the UK Home Office, anyone applying after November 24 under the Tier 2 intra-company transfer (ICT) category would be required to meet a higher salary threshold requirement of 30,000 pounds from the earlier 20,800 pounds.

The ICT route is largely used by Indian IT companies in UK and the country’s Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) had found earlier this year that Indian IT workers accounted for nearly 90 per cent of visas issued under this route. The motivation for the same appears to be the MAC’s belief that the current immigration policy is not incentivising employers to train and skill the UK workforce and that there are no reciprocal arrangements that provide the UK staff the opportunity to gain skills, training and experience from working in India.

The tightening of rules on post-study stay in the UK discourages students to work in Britain after completing their studies there; consequently, the number of those enrolled in British universities has halved from 40,000 to about 20,000 in the past five years. Nationals outside the EU, including Indians, will also be affected by new English language requirements when applying for settlement as a family member after two-and-a-half years in the UK on a five-year route to residency settlement in the UK.

Critics ask why it is being made harder for Indian companies in the UK to bring in skilled workers from outside the country when India is the third-largest investor in Britain and Indian companies are its largest manufacturing employer. India is UK’s second-largest international job creator — last year, India created 7,105 new jobs in Britain through 140 projects. India is likely to take up the visa issue with May during the visit.

Comparisons are also being made with visa rules for the Chinese, which are reportedly being granted more liberally and for longer durations. Since 2010, when May became Home Secretary, the number of Indian students studying at UK universities has declined while the number of Chinese students has risen from about 55,000 to 90,000.

May’s India visit is being seen as the UK’s first major test of its ability to carry through its policy objectives of building stronger partnerships with non-EU countries while at the same time introducing the tougher immigration regime that the government’s electoral constituency has demanded through the Brexit referendum.

(Monish Gulati is Associate Director, Strategic Affairs, at the Society for Policy Studies, New Delhi. The article is by special arrangement with South Asia Monitor/www.southasiamonitor.org)