BY M.R NARAYAN SWAMY

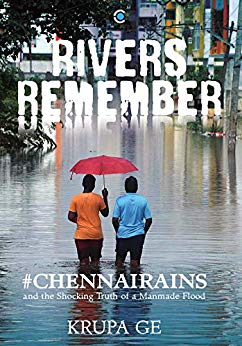

Title: Rivers Remember — #ChennaiRains; Author: Krupa Ge; Publisher: Context/Westland Publications; Pages: 218; Price: Rs 499

Writer and editor Krupa Ge spent over three years, from December 2015 to May 2019, talking to victims and volunteers of the devastating 2015 Chennai floods that drowned the city, causing chaos, death, destruction and unprecedented heartbreak. And she came to a firm conclusion: the floods were a man-made disaster and the Tamil Nadu government had an undeniable role in drowning clueless citizens without any warning.

But it was not just about momentary poor governance of December 2015. The Tamil Nadu government, the book says, also played an active role in sabotaging the city’s water bodies over the decades. On top of it all, there was no disaster management worth the name that could have softened the blows of 2015.

Krupa Ge’s investigation has an emotive tinge because her own childhood home was crushed in the calamity, destroying every single thing accumulated over the decades. “Everything is gone� life savings, a lifetime of everything,” she cries, a despairing feeling that must have similarly torn apart millions in Chennai. Yet Krupa Ge’s family survived; not everyone was so lucky.

The official excuse was that this was the rain of the century and so nothing more could be done. True, 1,218.6 mm of rains had pounded the city in November when the usual rainfall around this time was less than one third of this.

But not opening the sluice gates of the Chembarambakkam Reservoir to let the heavy rainwater flow out through the Adyar river into the sea was a major factor, the author says. A later damning CAG report found that the indiscriminate release of nearly 21,000 cusecs was made to save illegal encroachments in the foreshore area of the reservoir. Eventually, 29,000 cusecs of water was discharged continuously for 21 hours — from 6 p.m. of December 1 till 3 p.m. of December 3, in addition to the water from the upstream tanks and catchment area.

Gross bad urban planning – arising from greed – had virtually wiped out Chennai’s water bodies over the decades. The Centre had proposed setting up a flood protection wall or an embankment in Adyar river in 2008. The plan was never implemented. There was more: without paying heed to warnings from environmentalists and aviation experts, a 2,925-meter secondary runway of the Chennai airport was built on the flood basin of the Adyar in 2011, by erecting a bridge over it and hindering its path. Crush a river, and the river will take its revenge one day. Rivers remember.

Krupa Ge has a grouse against the national media, whose “silence was deafening and demeaning” even as Chennai turned into an island and was plunged into darkness with lives being lost – until the tragedy could not just be ignored. At the same time, Chennai came together to provide much needed succour to the flood victims. Strangers opened up their homes, restaurants provided resting places and food for free. Major cinema halls which had not been ravaged threw their doors open. Yet, those in the lowest echelons of the society were unable to access relief.

In contrast, there was no coordination between the central and state governments, leaving the Army and Navy clueless, she says. In one instance, 20 days after the flood, a government team offered a one-litre water bottle and one – yes, one — milk powder packet to a flooded hospital! Amidst the mass misery, AIADMK activists forced many volunteers to add stickers that had “Amma’s” face on flood relief materials.

For a week after the floods, Chennai’s streets were a mass of stinking piles of garbage thrown out by residents. But sanitation workers brought in from outside the city were poorly paid – many got as low as Rs 50 a day for their drudgery. The city’s grievance was not with the flood at all, Krupa Ge says. “Our problem was with the manner in which it was handled by the state.”