By Saket Suman

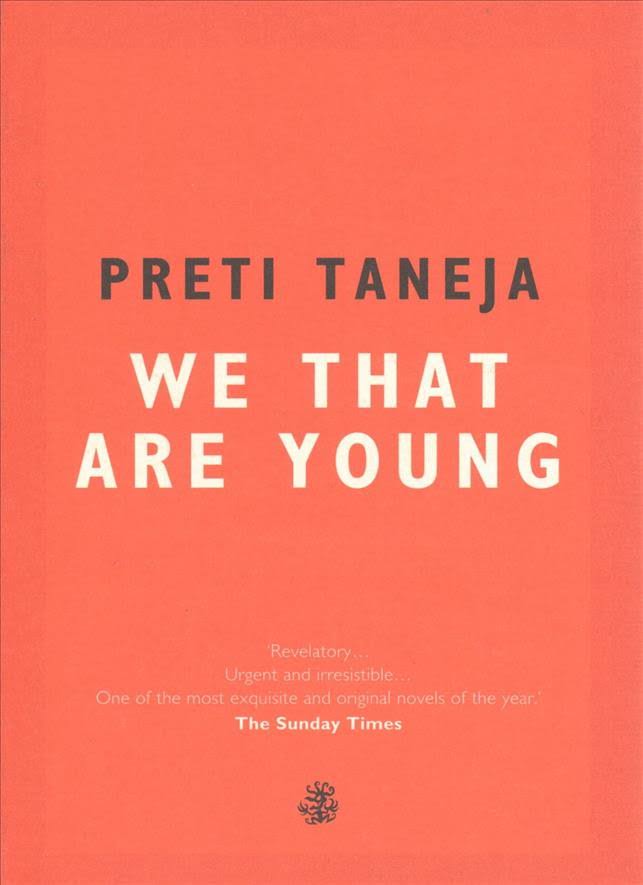

New Delhi– Her first novel is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s “King Lear” — told as a devastating commentary on contemporary India — and was welcomed with rave reviews in the UK. Now Preti Taneja’s “We That Are Young” is out in India — but will it make a mark in a market driven largely by light and popular reads, one that is moving far from Shakespeare as well as literary novels?

The author, in an email interview from London, told IANS that it took a long time for her to find a publisher in the UK as well. In fact, it was rejected by all mainstream London publishing houses.

“It takes brave, avant-garde editors who are politically engaged, who want to take risks and set trends, not follow them, who see the value (beyond the economic) in writing that breaks forms and experiments with language. Most importantly, it takes editors who believe in and trust their readers,” Taneja said.

“It takes brave, avant-garde editors who are politically engaged, who want to take risks and set trends, not follow them, who see the value (beyond the economic) in writing that breaks forms and experiments with language. Most importantly, it takes editors who believe in and trust their readers,” Taneja said.

Taneja insisted that such editors do exist and “books have to find them”. It may take a lot of persistence, as in her case, but ultimately it does happen.

“One look at the strength of some in the current generation: Their resilience, their awesome creativity, their commitment to speaking truth to power in the times we are living through tells me that. Literary or popular — both can be revolutionary — for me, readers without borders are the future of the world,” she quipped.

Taneja wanted to write about India and explore the colonial legacies of language and culture between India and England. “King Lear” was the right lens, she said, to examine what has come out of that, for good and bad; to think politically about the ways cultures shape each other and “how ideas of ‘the other’ are a two-way street”.

“Setting King Lear in India was a way of thinking about the fact that the world is messy, and formed by miscegenation. It’s not that people have double identities; it is more that we are forced to navigate dual realities. Fiction can reflect that, it can sound a warning to inspire action; by reflecting the worst, it can ignite hope for what we can make come next,” she reflected.

For the writer in Taneja though, it has been a wild ride. She had her structure — of telling the play from the perspective of five young people — at hand when she began. Much to her fortune, the scenes of “King Lear” broke down smoothly into that, but the change from play to novel form demanded a few flashbacks at the end.

“One major challenge was to write the big set pieces on their own terms, while retaining that connection to Shakespeare. So, the blinding scene and the storm scene — all of that was essential, but it had to be absolutely embedded as part of the world of the novel. They were easy to write; I drafted my storm scene while staying in a suburb on the outskirts of Delhi, in the middle of a monsoon that flooded the local basti. But they were difficult to get right. All writing is endless drafting,” she maintained.

Taneja said that living with her five characters was like being possessed. She was very sad writing and editing Radha but was constantly washing her hands while working on Jeet. When the book was published, she felt like they (the characters) had gone to party without her, and that was a kind of loss.

“Most of all, writing and editing in a very quiet house in Cambridge, UK, while the news was coming from India on everything from floods and smog, to holy men as politicians, women’s rights, protests, Kashmir — all of it was already in the book (or it went in) and that process was strange — as if I was living in many worlds and times at once,” Taneja added.

And, moreover, Taneja always thought “King Lear” explained so much about India and that it would be great to set the play in that context. When she later learned that Shakespeare’s works were brought to India as part of the East India Company and took root, it made a lot of sense, and added an important layer to her thinking about the plays as they are translated into different languages and forms around the world.

“Writing ‘We That Are Young’ was like an extended conversation with ‘King Lear’ — a lot of it was arguing over how to capture the language in my characters’ voices. I didn’t want to parrot or mimic it but build in the awareness that because of colonialism and Shakespeare’s enduring popularity, his phrases, his syntax, exist in our everyday speech, sometimes even without us realising it,” she concluded. (IANS)