By Vikas Datta

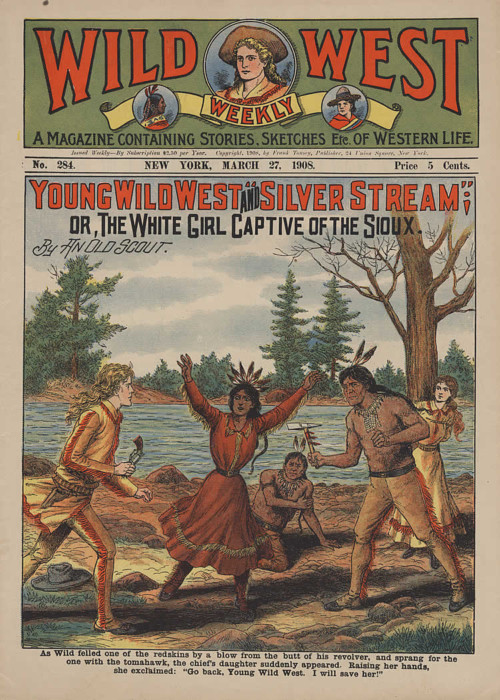

Bullets flying as gunmen confront each other in the streets or saloons, cowboys lassoing cattle on sprawling ranches across a starkly beautiful panorama, wagon-borne pioneers riding across boundless plains with a worried eye out for Red Indians, bounty-hunters, treasure hunts and more — a small part of American history has extended beyond its time and space to leave a global cultural impact.

But why has a period of some five decades of the 19th century in a large expanse of United States’ (then) empty middle become such a cultural phenomenon? How has the typical American genre of the “Western” inspired German, French and British writers, or Italian, East European and Indian film directors, and have admirers from Adolf Hitler to Joseph Stalin? And how realistic are the Westerns we read or see?

First, what do Westerns actually entail?

Set in the ‘Wild West’, the mostly uncharted, unsettled and loosely governed areas west of the Mississippi River, Westerns span from around the late 1840s to 1890 when the end of the frontier was officially declared (but may linger on to into the new century), have their own specific features, stock characters and settings from the cold mountains of the north to plains to the desert in the south (most common).

The plot may feature a lawman’s challenges from outlaws/Red Indians/powerful vested interests, a nomadic mysterious gunman riding into town or small, isolated homestead to rid it of threats, a wronged man’s quest to take revenge, fighting off Red Indians or outlaws to protect settlers, building up a ranch from scratch and fending off cattle rustlers or larger unscrupulous neighbours or the like.

The plot may feature a lawman’s challenges from outlaws/Red Indians/powerful vested interests, a nomadic mysterious gunman riding into town or small, isolated homestead to rid it of threats, a wronged man’s quest to take revenge, fighting off Red Indians or outlaws to protect settlers, building up a ranch from scratch and fending off cattle rustlers or larger unscrupulous neighbours or the like.

The characters include the cowboy, the drifter who is likely to be a gunslinger, quite possibly the “Fastest Gun in the West”, and sometimes something-or-the-other kid. Against them will be outlaws — bandits, rustlers, or highwaymen, unscrupulous business barons or savage/noble Red Indians. While the law is represented by judges and sheriffs — good, bad or ineffective — or US marshals, there will also be bounty hunters, homsteaders, (usually placid) townfolk, professional gamblers, preachers, prostitutes, and soldiers.

The genre in itself is even older than the classic Western era, originating in the early 19th century with American author James Fenimore “The Last of the Mohicans” Cooper when the frontier was more eastward. Its common tropes were established by the mid-century cheap but lurid “dime novels” (American versions of the British “penny dreadfuls”) with fictional exploits of real people like Billy the Kid, Kit Carson, Wyatt Earp, Wild Bill Hickok and so on, and subsequently, the pulp magazines.

Meanwhile, even before American Owen Wister’s “The Virginian” (1902), regarded as the first Western novel, or Zane Grey’s “Riders of the Purple Sage” (1912), there was already Austrian Carl Anton Postl alias Charles Sealsfield’s “Tokeah or the White Rose” (1829), Frenchman Gabriel Ferry’s “Le Coureur de Bois” and Irishman Thomas Mayne Reid’s “The Rifle Rangers” (both 1850).

Without setting a foot in the US, German author Karl Friedrich May, from the 1870s onwards, created a whole series of novels set in the American Old West, featuring Apache chief Winnetou and his White “blood brother” Old Shatterhand, making the genre popular in the German-speaking world.

In the modern era, Americans like Clarence Mulford (“Hopalong Cassidy” stories), Max Brand (Frederick Schiller Faust) and later Louis L’Amour, were complemented by English authors like J.T. Edson with his Civil War and other Westerns and Terry Harknett alias George G. Gilman.

But for those looking for the classic stuff couldn’t do better than read the books adapted into acclaimed Western films — say Walter Van Tilburg Clark’s “The Ox-Bow Incident” (1940) in which two drifters are drawn into a lynch mob, Roy Chanslor’s “The Ballad of Cat Ballou” (1956), which is darker than the Lee Marvin/Jane Fonda film, Stuart Lake’s “Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal” (1931), which inspired “My Darling Clementine”, Jack Schaefer’s “Shane” (1953), Charles Portis’ “True Grit” (1968) or Elmore Leonard’s revisionist “Hombre” (1961).

And how does the actual West compare with its cultural depiction? Well, though it was lawless and violent, there were no huge shootouts, the quickdraw showdowns were rare, guns were not very precise or rapidfire, gunfights and violent criminals were common elsewhere too, people carrying guns in most towns could get arrested than shot, and be more likely to die from disease or in an accident than to be killed in a gunfight or by Indians. And while there were white cowboys, most were likely to be black, Hispanic, Asian or Native American.

But why is the genre so popular? Has it something to do with its setting of yet untamed wilderness, personal codes of honour and direct justice (in a shooting showdown), some trappings of civilisation but not its social order, and the adventure?

And then, there is always something to be said for that ends with a ride into the sunset. (IANS)