By Vikas Datta

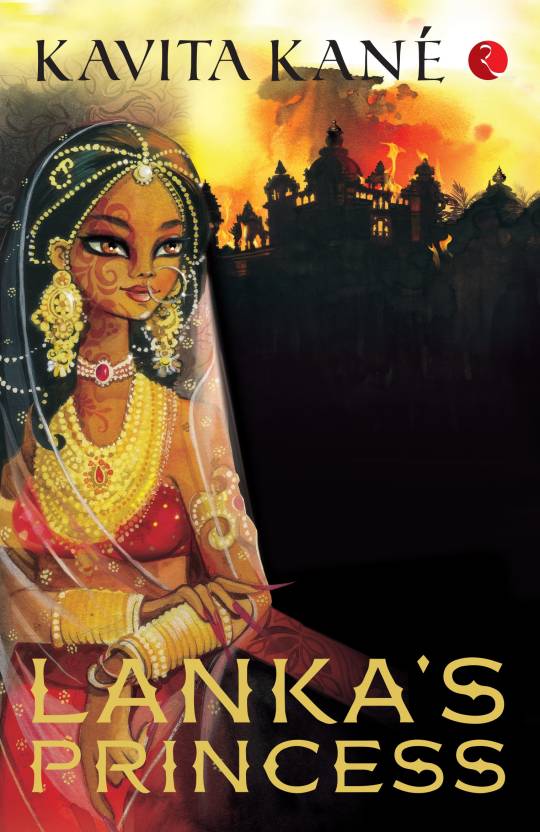

Title: Lanka’s Princess; Author: Kavita Kane; Publisher: Rupa Publications India; Pages: 280; Price: Rs 295

Like the space-time it is set in, Hindu mythology too seems to trace a circular course — in fiction. Its once unmitigated villains are being re-evaluated, their motives and actions re-assessed, and epics retold from their perspective. But while the great “demon” king, the Pandavas’ unknown brother and “jealous” cousin have had their say, what about a calamitous woman long-perceived as a cause of the war that destroyed Lanka?

But it was time that Surpanakha got her chance to tell her story of repression, rage, revenge — and eventual redemption.

We have long known her as Ravana’s younger sister, a “wanton” asura whose advances to Ram and Lakshman, the exiled princes of Ayodhya, were spurned and earned her horrific mutilation from Lakshman’s swift sword. Her subsequent complaint to her brother set in motion a chain of events that led to the death of almost every male relative. But do we know anything else about her — her past, her thoughts, her future?

Remedying the deficiency is author Kavita Kane, who has long been trying to give the overshadowed women — wives, mothers and sisters — of the great mythological epics a voice — and their due.

And after Karna’s wife Uruvi, Sita’s sister Urmila and the apsara Menaka, it is time for Meenakshi, the youngest child and only daughter of sage Vishravas and asura princess Kaikesi. It was her mother who named her Surpanakha, because of long sharp nails and equally sharp and destructive temper.

Meenakshi’s story cannot, however, be seen in isolation from her family, especially her brothers, the powerful and ambitious Ravana, the slow but solid (and unexpectedly perspicacious) Kumbha, and the righteous Vibhisana, and the growing tensions between her parents, and her father and eldest son.

But this is not where Kane begins her tale, which starts in another, later age, where a young prince, raised as a cowherd, returns to Mathura to reclaim his heritage.

Among the crowd, Krishna immediately identifies an old, hunchbacked woman, who makes her living by making sandalwood paste, as an “acquaintance” from an earlier life and approaches her. She is discomfitted by the attention of “an eerily familiar” but unrecognisable interlocutor, who seeks a favour, and promises to return. He does after fulfilling his primary mission, restores to proper form and reminds her of her previous life.

It is then a flashback to the hermitage of Vishravas as she is being born, and her mother’s disappointment at giving birth to a daughter. From then we follow the childhood of Meenakshi and her elder siblings, which give us insights into their latter, more-known selves. It also, through their examples, shows us how some human traits and social issues have been part of our lives in the ages.

And before the events segue into those we know as the Ramayana, we learn how Meenakshi’s bids at happiness in her trying life fail and what an elaborate revenge she plans and implements — though there are times when she balks at the cost it demands.

Her campaign doesn’t end on the battlefields of Lanka but continues well into Ram’s Ayodhya, though she finds herself unable to carry out the final part of her revenge due to the unexpected reactions from her prospective victims. It is then she finally understands the patterns of her life and fate.

The narrative returns to Mathura, where Krishna, who has comforted her with her eventual redemption, foresees — but forbears to tell her — her future (setting the stage for the next book?)

But, Kane’s fourth book is not just a mere retelling of the epic from the viewpoint of a significant but minor character, and providing more space to the likes of Ravana’s mother, wife Mandodari, and brothers as well as Sita, though it is her sister, who has a more vital role.

It also may not lead us to view Surpanakha more sympathetically (though we can understand her) but shows how epics are not about the struggles between “good” and “evil”, but of and between humans, of their choices, aspirations, their different social systems and outlooks. We read them not to find god but to know more about ourselves. (IANS)