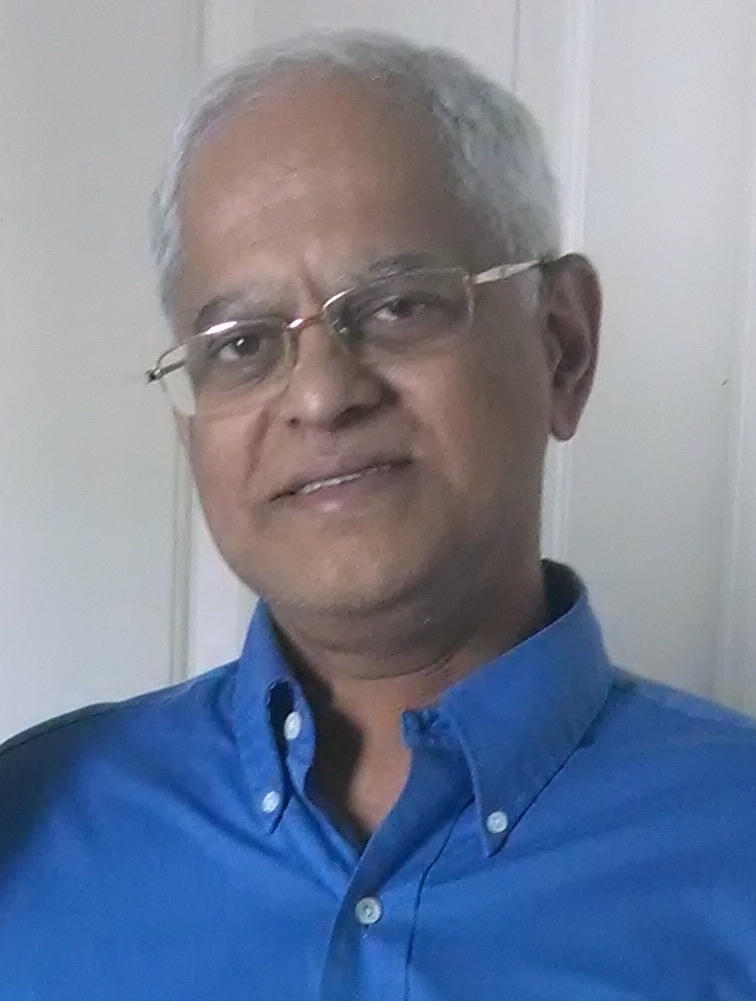

BOSTON–Ever since his grandmother told Mahabharata stories in his childhood, Kamesh Ramakrishna (Kamesh Aiyer) remained fascinated by this great epic. What he liked in Mahabharata? “The characters are complex — no one is completely good or bad,” he tells INDIA New England News.

Ramakrishna has just published his first novel entitled “The Last Kaurava.” It is based on the complex Mahabharata characters. In another words, it is “The Reimagined Mahabharata.”

In his introduction of the book, Ramakrishna says: “I imagined a highly evolved, non-literate and orally based culture in 850 BCE… I followed some ground rules. Nothing fantastic – no gods, goddesses, or demons; no magic; no magical weapons; no miraculous conceptions; no karmic explanations.”

In an exclusive interview with INDIA New England News, Ramakrishna talks about the novel and the characters.

Ramakrishna grew up in Bombay (now Mumbai) and completed his undergraduate studies at IIT-Kanpur. He went on to obtain a Ph.D. in computer science from Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh, specializing in Artificial Intelligence. He worked as a professor and a software engineer, received some patents, and was software architect for some foundational products. In addition, he also served as Chief Technology Officer for a startup, and in recent years, he has been a consulting software architect. He lives with his family in Massachusetts.

INDIA New England News: How long did it take you to write this novel and how long has this idea been in your mind?

Kamesh Ramakrishna: For the longest time, I have been an avid student of history, archaeology, myth & legends, science and philosophy. And the interconnection between these disciplines. I love story-telling!

I started thinking about this novel, a work of fiction using characters from the Mahabharata, a little over three years ago.

INE: Is this your first novel? How did you get the idea for this book?

KR: Yes, this is my first novel.

I have loved the Mahabharata, ever since my grandmother told me the story when I was a child. The characters are complex — no one is completely good or bad. At the same time, some characters are well-developed and others, even important ones, are not. I chose to write about Devavrata (Bhishma), arguably the most important character in the epic. He is the only person there from the start to almost the finish. Yet what we know about him is a stereotype, almost a caricature representing the “old guard” – he is perhaps the least visible and developed of all the characters.

I experimented by publishing two short vignettes in Kindle; I got positive feedback, that emboldened me to complete the novel.

INE: Why a Mahabharata-based novel?

KR: The Mahabharata has been a “peoples’ epic” for many centuries, with regional Mahabharata variants from all over India as well as Southeast Asia. Story tellers both new and traditional, performance artists, and even grandmothers everywhere, have been creating an enormous number of sub-plots and variations.

My book is very different from the Mahabharata – yes, I use several characters from the Epic. I also mostly follow the story-line. It requires that the reader to be flexible and open-minded enough to let my story play out. To be clear, I am not retelling the Mahabharata; this is a new work of fiction.

Two stories unfold in my book: the first explores the writing down of the Mahabharata. It parallels the episode from the very beginning of the Epic in which Ganesha, the elephant-headed God, agrees to transcribe the poem narrated by Vyaasa. And the second story, the major story pointed to in the title of the book, explores the life and choices of Devavrata-Bhishma.

A core fact anchors each story: the first story ties the writing of the Epic to the invention of the script called Brahmi, one native to South Asia. It is the first script whose letters are organized in a system based on how the sound is produced by the speaker.

There is an amazing, almost unbelievable, observation underlying this invention – writing does not seem to have taken off in South Asia till after Chandragupta Maurya around 300 B.C.E. There is evidence from contemporary visitors, like Megasthenes, that among themselves South Asian merchants made oral contracts. It looks like the culture of South Asia was non-literate at a time when the contemporary cultures to the West (Persian, Assyrian, Greek, etc.) were writing stories and maintaining written records. But from the earliest recorded times, South Asia has been seen as richer, more sophisticated, and highly evolved. At some point, the orally transmitted Epic was written down – scholars debate the date which I assume to be 850 B.C.E.. My novel conjures a story of how this came about with the invention of Brahmi.

The second story builds on the disappearance of the river Saraswati – modern geo-mapping technology allows us to date this event to about 2000 B.C.E.. I assume that this disappearance was an environmental crisis that led to the end of the Sindhu-Saraswati civilization. Large groups of migrants found their way to the Frontier of that time, marked by the small trading outpost of Hastinapur on the edge of the great forest covering the Gangetic plain. Unfortunately this area was already occupied by forest-dwellers who resisted the immigrants. The Kuru rulers of Hastinapur upto Shantanu struggled to cope with the stresses – Devavrata-Bhishma saw the opportunity to create a Kuru empire. But at the core was the conflict between the urban migrants and the native, forest-dwelling, non-urban population, a conflict with no hope for compromise. War would be the tragic outcome, the Great War of the epic being the dramatized residue of that traumatic memory.

The two stories are almost 1000 years apart! SO I have used some creative techniques to allow the reader to switch easily between one period and the other!

INE: What message should a reader get from your novel?

KR: I did not intend to provide any messages, but fiction can provoke reflection! Today, our world-encompassing culture is facing an environmental crisis. It is not the first made-by-humans (anthropogenic) environmental crisis. But for the first time in the history of the world, there is no way to escape from the current crisis, no place to escape to. We are not going to migrate out of this one!

In the era of the Mahabharata, the drying of the Saraswati was the crisis – the resulting migration was the challenge – the geography of Hastinapur forced that city to face the challenge – the personal/psychological woes that Devavrat/Bhishma faced in his life prepared him for his role as leader of Hastinapur – the limitations of his vision prevented him from fully comprehending how the culture would survive.

So our current crisis is both similar and different from the crisis in the Epic. Are there lessons to be learned in the Epic about addressing inescapable conflicts? I can only invite the reader to think about this.

INE: What percentage in this novel is fiction (different from the original epic) and what is based on facts of the epic?

KR: The novel is a work of fiction, a product of my imagination. Giving a percentage number is not really meaningful when the differences are so great.

Some parts of the novel use the characters and the narrative arc from the Mahabharata. The major characters are common to both. I’ve given some of them new “given” names to replace the descriptive names used in Vyaasa’s Mahabharata, for instance, Suyodhana replaces Duryodhana. The other changes are in the book. I’ve also created a few new characters with new names.

The story of how it came to be written is, of course, completely new, but even it has an analogy to the story of Vyaasa and Ganesha in the Epic.

I try to be consistent with what we know of the technologies of the period and the age. I followed some ground rules – nothing fantastic – no gods, goddesses, or demons; no magic or magical weapons; no miraculous conceptions; no karmic explanations. The story is set in 2000 B.C.E. – that’s the “Bronze Age”. I restricted myself to known Bronze Age technology – for instance, no nuclear weapons, but more to the point, no horses or iron or million-man armies. The archaeological evidence is that iron was rarely used and known to a few; transportation was by carts drawn by oxen or onagers (the “Asian wild ass”); that horses were not used by most cultures of that time; that even where horses were used, they did not pull war-chariots until four hundred years later; that neither stirrup, nor bridle, or bit existed, so horses were not ridden but were used to pull carts. By 850 B.C.E., this had changed, but long-distance trade was still a slow affair dominated by a few guilds and families. The people were not all that different from us – they loved, they hated, they were kind, they got angry, they acted without thinking, they plotted, they lied, they demanded the truth, etc. Not better than us, and not worse either. They were just like us.

INE: Who is the Last Kaurava and why? It can be debatable, isn’t it?

KR: You are absolutely right! It is debatable. What I really do is … no… I can’t tell you. A hint: the title can be understood in many ways.

INE: Who are your three favorite characters in Mahabharata and why?

KR: I am drawn to the characters who are important, but whose personal narrative and emotions are not well developed. Satyavati, Drona, Kunti, Pandu, Dhritarashtra, … the list of interesting characters is long. But “interesting” is not the same as “favorite”!