By Vikas Datta

Much before the term “Renaissance Man” came into vogue, he was one in what eventually became India. A prolific poet, historian and writer, he also introduced two music forms – ghazal and qawwali – popular to this day, is credited with developing two styles of classical music – khayal and tarana – as well as the tabla and sitar. But his most notable feat was using a local vernacular so adroitly that seven centuries hence it is the most commonly-used language across the South Asian subcontinent.

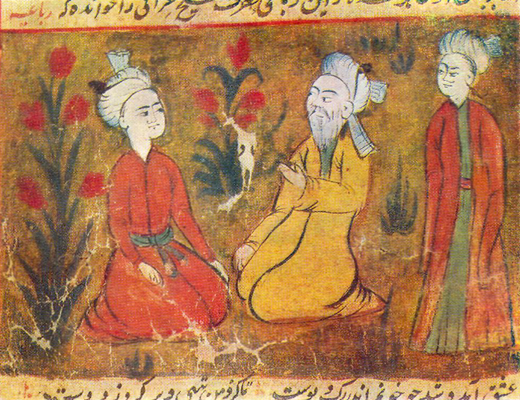

And Ab’ul Hasan Yamin ud-Din Khusrow (c. 1253-1325) or Amir Khusro, as we usually know him, seemed to epitomise the assimilative nature of India.

The son of a Turkic Hazara noble, forced to leave his homeland near Samarkand by Genghis Khan’s invasion and found shelter at the court of Sultan Iltutmish, and an Indian mother from a Rajput tribe, he was born in what is now Uttar Pradesh’s Etah district. Beginning imperial service as a soldier, he became court poet to Sultan Balban’s nephew in 1271 and soon enjoyed royal favour, serving seven monarchs of Delhi spanning the Mamluk or Slave Dynasty, the Khaljis and the Tughlaqs.

Besides his diwans – “Tuhfa-tus-Sighr (Offering of a Minor)”, “Wastul-Hayat (The Middle of Life)”, “Ghurratul-Kamaal (The Prime of Perfection)”, “Baquia-Naquia (The Rest/The Miscellaneous)” and “Nihayatul-Kamaal (The Height of Wonders)”, finished a few days before his death, other notable works include “Mathnavi Duval Rani-Khizr Khan”, a hauntingly beautiful but tragic poem about the love between Gujarat’s princess and Sultan Alauddin’s son, “Mathnavi Noh Sepehr (Mathnavi of the Nine Skies)” on his perceptions of India, a collection of five classical romances including of Shireen-Khusrau, and Layla-Majnun, as well as prose and histories.

But it is his poetry , both Persian and then Hindvi (“Khusro darya prem ka, ulti wa ki dhaar/Jo utra so doob gaya, jo dooba so paar”) that holds centrestage – even when he combines both as in this oft-quoted example, and glides between them within a line.

“Zehal-e miskin makun taghaful, duraye naina banaye batiyan/Ki taab-e hijran nadaram ay jaan, na leho kaahe lagaye chhatiyan/Shaban-e hijran daraz chun zulf wa roz-e waslat cho umr kotah, Sakhi piya ko jo main na dekhun to kaise kaatun andheri ratiyan…”

And his Persian poetry is as grand. Take either this ghazal (will be familiar as a qawwali for Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan fans): “Nami danam chi manzil bood shab jaay ki man boodam/Baharsu raqs-e bismil bood shab jaay ki man boodam (I don’t know which place I was at last night/Flailing were half-slain tormented victims (of love) around me where I was last night)”.

Or this one (also rendered as a qawwali): “Khabaram raseed imshab ki nigaar khvahi aamad/Sar-e man fida-e raah-e ki sawaar khvahi aamad! (There came news tonight that you, oh beloved, would come/Be my head sacrificed to the road along which you will come riding)”, “Kashish ki ishq daarad naguzaradat badinsaa/Ba-janazah gar nayai ba-mazaar khvahi aamad (Love’s attraction will not leave you unmoved/ If you don’t join my funeral prayer, you will definitely turn up at my grave)” and ending: “Baya aamadan raboodi, dil-o-deen sab chu Khusro/Che shavad agar badinsaa, do se baar khvahi aamad (The first time you came, you took away Khusro’s heart and faith/What will you happen if you come again?)”.

It is dedicated to his spiritual master – Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya as are these qawwalis in a more familiar language but a very different cultural idiom: “Chhap tilak sab cheeni ray mosay naina milaike/Prem bhatee ka madhva pilaike…. Khusrau Nijaam kay bal bal jayyiye/Mohe suhaagan keeni ray mosay naina milaike”, “Main to piya say naina lada aayi rae.. Khusrau Nijaam kay bal bal jayyiye/Main to anmol cheli kaha aayi rae…”, and “Aaj rang hai hey maan rung hai ri/More mehboob kay ghar rang hai ri… Mohe pir paayo Nijamudin Auliya/Nijamudin Auliyaa mohay pir paayo.”

His inventiveness never stopped – there were his clever riddles, some containing their own answers: “Saawan bhaadon bahut chalat hai/Maagh paus mein thodi/Amir Khusro yun kahay/Tu boojh paheli mori” and dual ones with one answer: “Ghar kyun andhiyaara? Faqeer kyun barhbarhaya? Diya na tha” and “Pundit kyun na nahaya? Dhoban kyun maari gayi? Dhoti na thi.”

And then who can forget the lament of generations of brides: “Kaahe ko biyahi bides, re, lakhi Baabul moray…”

There have been studies innumerable on Khusro, but unlike many of his counterparts – eg. Shakespeare, Dante, Schiller, Baudelaire and so on, he (or for that matter, several of his regional successors like Tagore or Iqbal) have yet to get the ultimate literary accolade – appearances in fiction. Anybody out there interested?