By Saket Suman

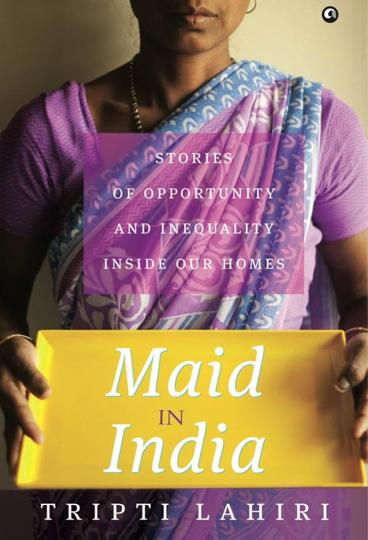

Book: Maid In India; Author: Tripti Lahiri; Publisher: Aleph; Pages: 314; Price: Rs 599

Do you have a domestic help at home to assist your family with household chores? When was the last time you stopped to take a close look at all that she goes through? Perhaps, never. This rare gem of scholarship brings their stories — of migration, pain and constant deprivation — to the fore, while reminding us of the gap between what we say we believe in, and what we actually practise in our day-to-day lives.

Titled “Maid in India”, this work of nonfiction is a result of meticulous research, which shows as one flicks through its pages. The author goes back to historical sources, ranging from scriptures to ages-old autobiographies and memoirs that mention the presence of maids in our society, to bust, point by point, all the myths that we associate with the women who work in our homes and homes around us.

The author points out that India has always had servants in some form or another, but what was once a trickle has now turned into a steady stream of women and men leaving their villages to work mostly in one of the five big cities of India. Lahiri presents and elaborates on all the reasons that may have led to this flourishing business of utmost deprivation and neglect. She also paints a thought-provoking sketch of how the trend of domestic help has been changing over time in India and elsewhere.

The author points out that India has always had servants in some form or another, but what was once a trickle has now turned into a steady stream of women and men leaving their villages to work mostly in one of the five big cities of India. Lahiri presents and elaborates on all the reasons that may have led to this flourishing business of utmost deprivation and neglect. She also paints a thought-provoking sketch of how the trend of domestic help has been changing over time in India and elsewhere.

But there is a larger narrative that the author has themed her book around.

“Two-thirds of all domestic help employed by families are women and that share rises to 80 per cent if workers whose duties take place outside the house are included. That is almost the exact opposite of the state of affairs at the start of the twentieth century, when women supplied just a third of household help,” she writes, while also reminding us that the most recent figures show that domestic work absorbs more than eight per cent of urban female workers, compared to less than one per cent of male workers.

Citing examples from scriptures and other ancient texts, the author blames the “traditional view of housework” for this skewed distribution of household work between men and women.

She then goes on to debunk the many myths around maids that most of us have thought to be true. The readers are reminded that, in the past, everyone’s place — whether maid, ayah or cook, sahib or memsahib — was well understood. There were clear rules for negotiating (and maintaining) the vast chasm between the two sides. Today the story is different and “represents oh-so-many failures on the part of the Indian state over oh-so-many decades”.

From in-depth reporting in the villages from where women make their way to upper-class homes in Delhi and Gurgaon, to courtrooms where the worst allegations of abuse get an airing, and a peek into homes up and down the class ladder, “Maid in India” is an illuminating and sobering account of the complex and troubling relations between the domestic help and those she serves.

Equally interesting is the ease with which the author, Tripti Lahiri, succeeds in communicating her findings. Her simple yet detailed narration coupled with a striking choice of words may partly be a result of her journalistic career, but the depth and analysis that she displays is that of a seasoned researcher.

It is this that make this book, despite its heavy dose of facts, figures and historical references, a sound read. A title dealing with subjects as intense as this often tends to arouse disinterest in its readers with its thesis-like narrative.

To be able to break this monotony is the forte of an ideal nonfiction writer and Lahiri, with this book, has announced her arrival. The book at hand will perhaps live longer than the praise it will inevitably elicit.

This book also comes at a time when the objectivity of nonfiction books is challenged as they are increasingly turning into propaganda tools and PR exercises. Lahiri has set a benchmark for this genre. (IANS)