By Liz Mineo

Harvard Staff Writer

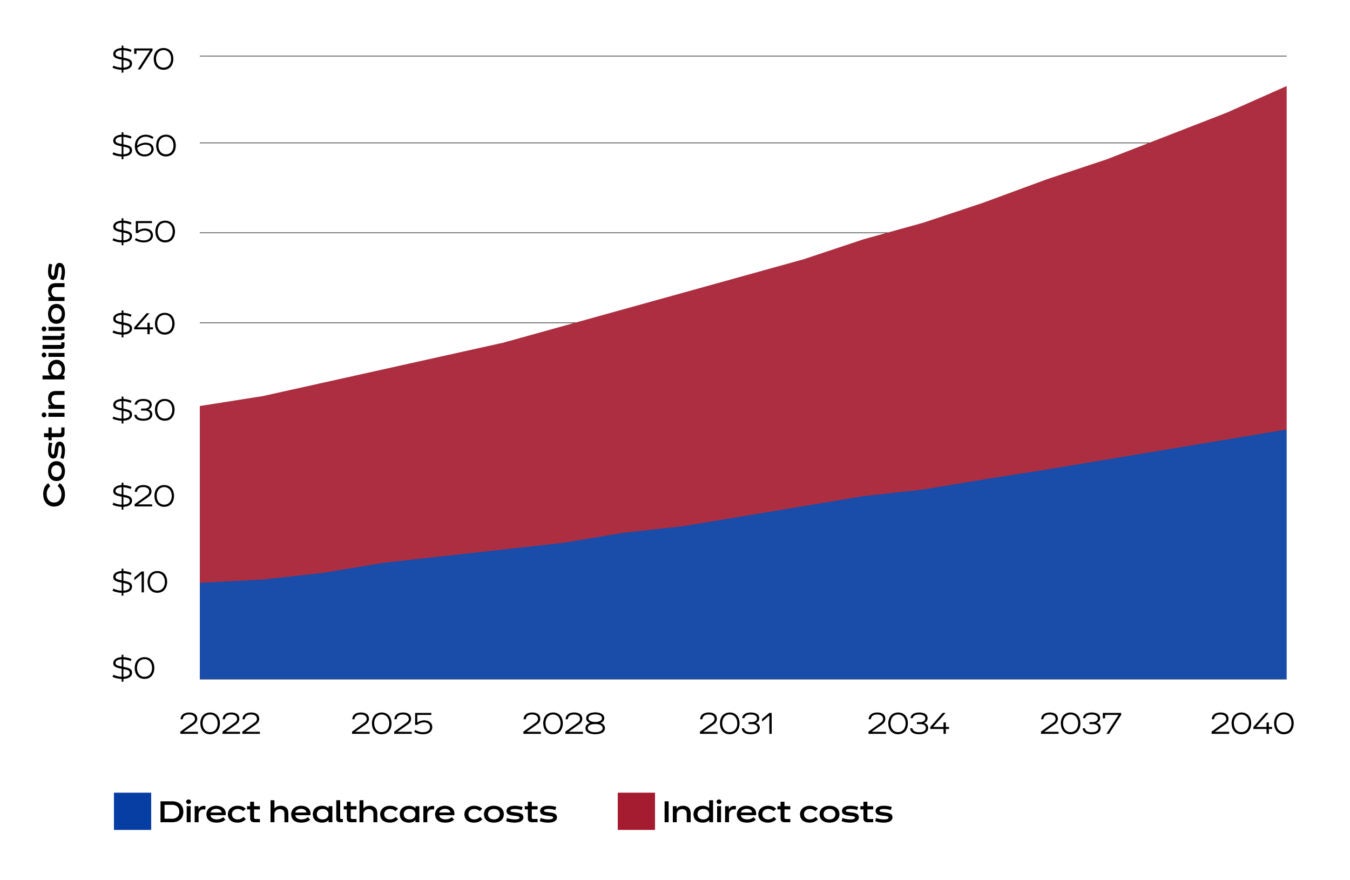

With high-risk drinking on the rise across the nation, experts project the annual cost of treating alcohol-associated liver disease, or ALD, will more than double over the next two decades, increasing from $31 billion in 2022 to $66 billion in 2040.

The recently released report was led by Jovan Julien, a postdoctoral research fellow at Harvard Medical School, and Jagpreet Chhatwal, director of the Institute for Technology Assessment at Massachusetts General Hospital. It depicts a bleak scenario: an economic and public health crisis and a warning for planners and policymakers.

“The idea of drinking has become normalized in our culture,” said Julien, the report’s lead author, “and therefore the burden, both in terms of health and economic costs, has become one that we’ve become desensitized to.”

But the damage and deaths are preventable, said Chhatwal, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School.

“We can substantially reduce both the disease burden and the economic burden,” Chhatwal said. “We need interventions and policy-level actions to combat both the disease and its rising costs.”

The key would involve multipronged approaches to prevent people from reaching a level of chronic or regular heavy drinking. The National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defines heavy drinking as four drinks per day and 14 per week for men and three per day and seven per week for women.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines recommend that adults either avoid drinking altogether or do so in moderation by having no more than two drinks a day for men or one for women.

The country must prepare for the impact of liver disease caused by excessive drinking, said Chhatwal. The paper estimated that from 2022 to 2040 the total costs will reach $880 billion: $355 billion in direct healthcare-related costs and $525 billion in lost labor and economic consumption. “That is not a small number, by any means,” he said.

But the number of deaths from alcohol-related causes is not small either. According to the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 140,000 people die every year in the U.S. due to excessive drinking. Those numbers are comparable to that of the opioid crisis, said Chhatwal. The CDC reported 106,699 drug overdose deaths in 2021.

“The numbers of deaths for both alcohol-related causes and opioids overdose are not far from each other,” said Chhatwal. “Drinking is socially acceptable, and drugs are not, so it doesn’t strike people that drinking can be harmful. But it is clearly harmful.”

The report predicts that if high-risk drinking trends persist, in 20 years about 956,000 people will die annually from ALD. Among them will be higher percentages of women and young people as cases among those populations are rising at a faster clip. In fact the percentage of ALD costs associated with female drinkers are expected to increase by nearly 50 percent in the next two decades.

Projected yearly alcohol-related costs in U.S.

Source: “The Rising Costs of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease in the United States”

During the pandemic, alcohol consumption increased with lockdowns, relaxed policies for alcohol delivery, and people working from home. Many who were moderate drinkers before became high-risk drinkers. A previous study showed that the two years of the pandemic will result in at least 8,000 additional deaths from alcohol-related causes in the next decade.

To Julien, one of the major takeaways of the study is the increase in heavier drinking among women and young people during COVID.

“That increase in drinking consumption can have residual impacts throughout their life course,” said Julien. “And so, both for the drinkers themselves and for policymakers, who are making policies that will impact folks across their life course, it’s important to consider what are potential interventions that can either reverse or control for some of these changes in behaviors that these particular cohorts have had.”Chhatwal said political and public health leaders should be considering programs to raise awareness about the effects of high-risk drinking and the development of effective therapies to treat advanced liver disease.

“There is underlying stress in society,” said Chhatwal. “We need to think about how to reduce that stress because that’s partially responsible for high-risk drinking. Some people see drinking as a coping mechanism, but it should not be a coping mechanism. There must be multipronged approaches to address this alcohol consumption crisis.”

Early mortality, due to ALD and other diseases that are preventable, is harmful to families, communities, and society in general, said Julien. Studies like theirs aim to present economic evidence to health officials and decision-makers, who have the responsibility to act.

“We’ve quantified, in a sense, what are some of the health and economic burdens of alcohol-associated liver disease,” said Julien. “We’ve tried to quantify what are some of the impacts, but there are many others that we can’t put a specific number to. And while the economics of it captures some quantifiable aspect of loss of life, it doesn’t capture the hole that’s left in a community when someone dies early, particularly from a hard and devastating disease, which is late-stage liver disease.”

(Reprinted with permission from the Harvard Gazette.)