By Vikas Datta

Remember “Ghostbusters”? The 1984 film about three parapsychologists taking on supernatural phenomenon in New York sparked off a whole universe of spin-offs across various media – a reboot version comes out in July with women replacing the original male cast. But the occult detective fiction genre has always been popular and enduring too, having been around for over a century and half now, and some of its earliest heroes still active – even in our technological age.

The genre has always had loyal readers bringing together as it does, two uniquely human obsessions – mysteries and the supernatural, though by defying rules set by renowned detective fiction writers in the early 20th century – like “All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course” (Second of Ronald Knox’s 10 Commandment of Detective Fiction) and that “It must be realistic in character, setting and atmosphere. It must be about real people in a real world” (Third of Raymond Chandler’s Ten Commandments).

The genre has always had loyal readers bringing together as it does, two uniquely human obsessions – mysteries and the supernatural, though by defying rules set by renowned detective fiction writers in the early 20th century – like “All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course” (Second of Ronald Knox’s 10 Commandment of Detective Fiction) and that “It must be realistic in character, setting and atmosphere. It must be about real people in a real world” (Third of Raymond Chandler’s Ten Commandments).

Even Sherlock Holmes, whose some cases seem supernaturally tinged but are proven to have a human agency, said: “This agency stands flat-footed upon the ground, and there it must remain. The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply.” (“The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire”, 1924).

These rules no longer bind but this particular one was breached right from the start. Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841) is one of the first instances of detective fiction but in 1855, Irish-American writer Fitz James O’Brien had his supernatural expert Harry Escott investigate a ghostly being in “The Pot of Tulips” and an invisible one in “What Was It? A Mystery” (1859).

The stories in Sheridan Le Fanu’s “In a Glass Darkly” (1870) were supernatural cases dealt by physician Dr. Martin Hesselius while his colleague Dr. Abraham Van Helsing in Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” (1897) is the one who realises the true nature of the threat and can deal with it since he possesses the requisite knowledge.

Apart from various remakes of Dracula, he has also carved out his own presence in many other works – novels like P.N. Elrod’s “Quincy Morris, Vampire” (2001) and John Marks’ “Fangland” (2007), films like “Van Helsing” (2004), TV shows like “Penny Dreadful” (2014) and a spate of comic books.

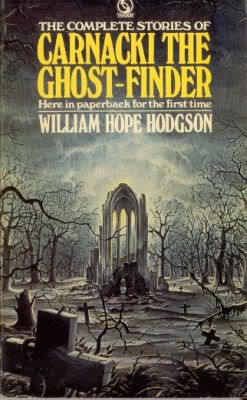

However the genre’s two most representative are Flaxman Low and Thomas Carnacki, the “Ghost-Finder”.

Appearing in 13 stories published between 1898 and 1899, Flaxman Low (the pseudonym for “one of the leading scientists” of the Victorian era with the real name never disclosed) was created by E. and H. Heron, who happened to be the British mother and son pair of Kate O’Brien Ryall Prichard and Hesketh Hesketh-Prichard, a Jhansi-born explorer, cricketer, soldier and expert sniper.

Like Holmes, Low uses his encyclopaedic knowledge (of the supernatural, in his case) and highly-honed observation to solve several macabre cases of hauntings. He also has involves many unprepared associates in his adventures, the best of which are “The Story of Baelbrow” where an ephemeral, harmless ghost takes on a more material and lethal form, “The Story of the Grey House” where numerous residents have been found mysteriously hanged but no rope is ever found, and “The Story of Medhans Lea” where a house is afflicted by a a child’s crying, and a sinister black-garbed figure with a horrifying laugh.

But it is William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki, with his camera, his (fictional) Electric Pentacle safeguard and the (fictional) ancient “Sigsand Manuscript”, who has proved to be more viable. His creator only wrote nine stories – six published in The Idler 1910-12 and three much later – but other authors have written nearly four dozen, more right down to Sam Gafford’s “Carnacki: The New Adventures” (2014).

All stories follow the same format – Carnacki invites four friends (including Dodgson, the narrator) to dinner at his home, No 472, Cheyne Walk (in London’s Chelsea) and hear his latest tale. After dinner, he lights his pipe, everyone settles into their favourite chairs, and he tells about his latest case of probing an unusual haunting, answers a few questions and ushers his guests out.

What makes the tales riveting is that it is only in the end do we know whether it was a supernatural or human agency, usually for criminal purposes, was involved. There is one which has both! What adds to the appeal is there are situations which leave even Carnacki petrified. His best include “The Gateway of the Monster” where he realises he has undermined his own defence and is lucky to escape with his life, “The Horse of the Invisible” and the disturbing “The Hog”.

There are many more right down to the present but these Victorian and Edwardian era stories have their own charm – and effect. Read them at night at your own peril!