By Saket Suman

Title: By Saket Suman (10:34)

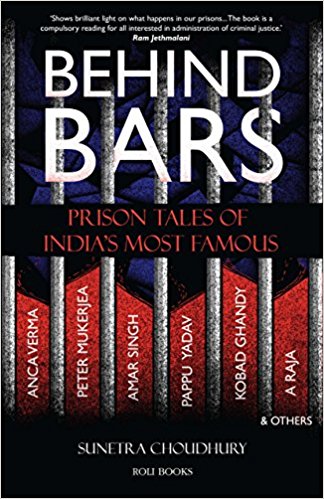

Title: Behind Bars: Prison Tales of India’s Most Famous; Author: Sunetra Choudhury; Publisher: Roli Books; Pages: 266; Price: Rs 395

Jail is a fearsome word for almost everybody and the general perception that revolves around the lives of inmates — that they lead a miserable life with yucky food, little care and all things contrary to comfort — is challenged in this well-researched offering that attempts to throw sufficient light on the “prison tales of India’s most famous”.

Penned by journalist and news anchor Sunetra Choudhury, the book takes its readers on an unusual ride through many jails in the country and shows how the treatment that the inmates receive may vary from person to person. Those that people think have been punished by the law, the book reminds, may well be leading a comfortable life inside the prison.

What is more astonishing is the fact that Choudhury provides enough evidence to suggest that these high-profile inmates are not only at ease in prison but also operate as easily from jail as they do outside. No matter how grave the charges are, the jail term can be quite an easy life for those with strong political backing or comfortable economic status, the author claims.

Choudhury’s book is an eye-opener of sorts. Not that we do not necessarily know about the comfortable lives many convicted have led or are leading inside the jails, but this book is perhaps the first detailed insider’s account into their lives. In the process, Choudhury provides enough evidence and secondary research to suggest that there is an underground economy of the jails that thrives on the comfort that goons receive in prisons.

Choudhury’s book is an eye-opener of sorts. Not that we do not necessarily know about the comfortable lives many convicted have led or are leading inside the jails, but this book is perhaps the first detailed insider’s account into their lives. In the process, Choudhury provides enough evidence and secondary research to suggest that there is an underground economy of the jails that thrives on the comfort that goons receive in prisons.

The book is based on extensive first-hand interviews with some of India’s most well-known inmates and the author provides the readers a peek into VIP life in prison. Perhaps for the first time, India’s most famous prisoners share their own stories — ranging from air conditioners in cells to food from five-star hotels, from cushy beds to private parties — and how they negotiate life in prison or the so-called “jail-ashram”.

With extraordinary details of the life inside prison and the sorry state of hundreds of undertrials languishing in jails, this book questions the primary purpose of imprisonment — is it actually reform, punishment or just misusing the system we are a part of?

The author creates portraits of 13 well-known figures, who have either spent or are spending their terms in jails across the country. While politicians Amar Singh, A. Raja and Pappu Yadav grab eyeballs, the tales of others who find mention are equally thought-provoking. Anca Verma, the wife of arms dealer Abhishek Verma, and Star India CEO Peter Mukherjea make curious case studies too.

Apart from certain depictions in popular culture or the occasional news report, there is little information about how rules are bent and law takes a backseat when it comes to people like Sanjeev Nanda, Vikas and Vishal Yadav, Anca Varma and Manu Sharma, who were given special benefits and often sent out on parole and furlough for “good behaviour”.

How unfair is the treatment that inmates receive inside the jails?

“If you steal 1,000 rupees, the hawaldar will beat the shit out of you and lock you up in a dungeon with no bulb or ventilation. If you steal 55,000 crore rupees then you get to stay in a 40-foot cell which has four split units, internet, fax, mobile phones and a staff of 10 to clean your shoes and cook you food,” Anca Verma says in the book.

In similar fashion, the author has sourced first-hand experiences of the rich, powerful and well to do to make this book a credible insight into the malfunctioning of our jails and the corruption that has enabled these powerful convicts to take advantage of the system.

Choudhury reminds readers that such VIP treatment is not a new phenomenon but has been a regular practise in many Indian jails, dating to Charles Sobhraj’s time in the late 1970s. But at the same time, she regrets, the poor life that other inmates lead inside the jails goes unnoticed too.

Quoting the increasing number of deaths in Tihar Jail every year, Choudhury makes a conscious effort to strike a balance between the extravagant lives of the powerful and shabby treatment that the helpless receive. The larger message of the book is a paradox of sorts as even though Choudhury says that “we only sit up and take notice when it is a familiar face that’s gone behind bars” , the majority of her book, like its title, too narrates the tales of the powerful.

; Author: Sunetra Choudhury; Publisher: Roli Books; Pages: 266; Price: Rs 395

Jail is a fearsome word for almost everybody and the general perception that revolves around the lives of inmates — that they lead a miserable life with yucky food, little care and all things contrary to comfort — is challenged in this well-researched offering that attempts to throw sufficient light on the “prison tales of India’s most famous”.

Penned by journalist and news anchor Sunetra Choudhury, the book takes its readers on an unusual ride through many jails in the country and shows how the treatment that the inmates receive may vary from person to person. Those that people think have been punished by the law, the book reminds, may well be leading a comfortable life inside the prison.

What is more astonishing is the fact that Choudhury provides enough evidence to suggest that these high-profile inmates are not only at ease in prison but also operate as easily from jail as they do outside. No matter how grave the charges are, the jail term can be quite an easy life for those with strong political backing or comfortable economic status, the author claims.

Choudhury’s book is an eye-opener of sorts. Not that we do not necessarily know about the comfortable lives many convicted have led or are leading inside the jails, but this book is perhaps the first detailed insider’s account into their lives. In the process, Choudhury provides enough evidence and secondary research to suggest that there is an underground economy of the jails that thrives on the comfort that goons receive in prisons.

The book is based on extensive first-hand interviews with some of India’s most well-known inmates and the author provides the readers a peek into VIP life in prison. Perhaps for the first time, India’s most famous prisoners share their own stories — ranging from air conditioners in cells to food from five-star hotels, from cushy beds to private parties — and how they negotiate life in prison or the so-called “jail-ashram”.

With extraordinary details of the life inside prison and the sorry state of hundreds of undertrials languishing in jails, this book questions the primary purpose of imprisonment — is it actually reform, punishment or just misusing the system we are a part of?

The author creates portraits of 13 well-known figures, who have either spent or are spending their terms in jails across the country. While politicians Amar Singh, A. Raja and Pappu Yadav grab eyeballs, the tales of others who find mention are equally thought-provoking. Anca Verma, the wife of arms dealer Abhishek Verma, and Star India CEO Peter Mukherjea make curious case studies too.

Apart from certain depictions in popular culture or the occasional news report, there is little information about how rules are bent and law takes a backseat when it comes to people like Sanjeev Nanda, Vikas and Vishal Yadav, Anca Varma and Manu Sharma, who were given special benefits and often sent out on parole and furlough for “good behaviour”.

How unfair is the treatment that inmates receive inside the jails?

“If you steal 1,000 rupees, the hawaldar will beat the shit out of you and lock you up in a dungeon with no bulb or ventilation. If you steal 55,000 crore rupees then you get to stay in a 40-foot cell which has four split units, internet, fax, mobile phones and a staff of 10 to clean your shoes and cook you food,” Anca Verma says in the book.

In similar fashion, the author has sourced first-hand experiences of the rich, powerful and well to do to make this book a credible insight into the malfunctioning of our jails and the corruption that has enabled these powerful convicts to take advantage of the system.

Choudhury reminds readers that such VIP treatment is not a new phenomenon but has been a regular practise in many Indian jails, dating to Charles Sobhraj’s time in the late 1970s. But at the same time, she regrets, the poor life that other inmates lead inside the jails goes unnoticed too.

Quoting the increasing number of deaths in Tihar Jail every year, Choudhury makes a conscious effort to strike a balance between the extravagant lives of the powerful and shabby treatment that the helpless receive. The larger message of the book is a paradox of sorts as even though Choudhury says that “we only sit up and take notice when it is a familiar face that’s gone behind bars” , the majority of her book, like its title, too narrates the tales of the powerful. (IANS)