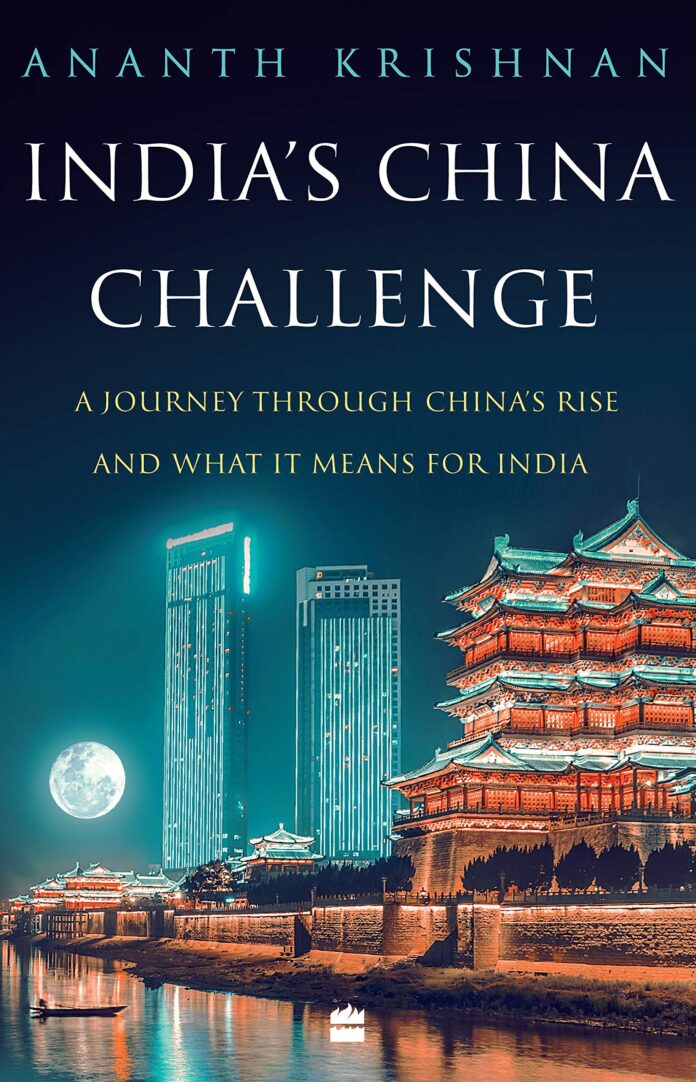

New Delhi– If the pandemic is accelerating existing political trends in China, it is also sharpening the debate about the China model – a debate that is unfolding both within the country and around the world,” writes Ananth Krishnan, the Beijing correspondent of The Hindu newspaper in “India’s China Challenge – A Journey Through China’s Rise And What It Means For India”.

For supporters of the model, he writes, it has underlined the strengths of centralised authoritarianism. For detractors, it has showed why a system that views transparency as a threat failed at a very crucial test. This was a debate that, in the spring of 2020, was heating up

within China too.

In the aftermath of the initial response, real estate tycoon Ren Zhiqiang penned a searing essay criticising the political path under Xi

Jinping, voicing a sentiment he had heard in Beijing, from academic and business circles, deeply uncomfortable with what they saw as political regression.

“The other view that the pandemic has accelerated in China is that the country now has a moment of strategic opportunity to push its

global ambitions – a dominant goal of the Xi era, as we have seen – and that it must continue challenging the US. As the leading Chinese strategic affairs thinker Yan Xuetong of Tsinghua University told me, the global response to the pandemic had ‘shown the lack of global leadership’,” Krishnan writes in the book, which has been published by HarperCollins.

Yan’s view, which is being echoed in Beijing, is that regardless of China’s initial missteps, the chaotic US response, followed by the spread of protests over the summer of 2020 ignited by the Black Lives Matter movement, had ultimately bolstered China’s position in

the world.

The other view that the pandemic has accelerated in China is that the country now has a moment of strategic opportunity to push its global ambitions – a dominant goal of the Xi era, as we have seen – and that it must continue challenging the US..Yah’s view, which is being echoed in Beijing, is that regardless of China’s initial missteps, the chaotic US response, followed by the spread of protests over the summer of 2020 ignited by the Black Lives Matter movement, had ultimately bolstered China’s position in the world.

‘A world without global leadership may last for a decade or more,’ Yan told Krishnan. ‘The competition between China and the US prevents the collective leadership of major powers. Therefore, although there is a vacuum for global leadership, no country seems ready to fulfil it in the near future. Henry Kissinger said that the pandemic will alter the world. Nevertheless, I would argue that it only strengthens the existing international political trends rather than change them.”

The Party, Krishnan writes, is convinced it is still on track to achieve its goals for the ‘two centenaries’: to build what it calls ‘a moderately prosperous society’ by the time the Party marks its 100th anniversary in 2021, and have in place ‘a modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced and harmonious’ by 2049, when the PRC turns 100. The Party is also working to build a ‘world-class military’ by 2050 – in other words, one that will be able to rival the US militarily.

The Party may be convinced of it, but that by no means implies that China’s forward march is an inevitability. The CPC faces serious challenges, both at home and abroad. Some are of its own making. The political transformations we have seen may have confirmed Xi’s

unrivalled standing in the Party – elevating his status to that of Mao Zedong and Deng – but it also signalled the dismantling of the model of collective leadership that Deng had left as his legacy.

It was a model that many even in the Party believe allowed China to escape the fate of other authoritarian and communist states; it was an authoritarian country without a dictator, a communist nation that embraced state-led capitalism, and gave its citizens economic and social liberties lacking even in some democracies.

The other view that the pandemic has accelerated in China is that the country now has a moment of strategic opportunity to push its

global ambitions – a dominant goal of the Xi era, as we have seen – and that it must continue challenging the US. As the leading Chinese strategic affairs thinker Yan Xuetong of Tsinghua University told me, the global response to the pandemic had ‘shown the lack of global leadership’.

His view, which is being echoed in Beijing, is that regardless of China’s initial missteps, the chaotic US response, followed by the spread of protests over the summer of 2020 ignited by the Black Lives Matter movement, had ultimately bolstered China’s position in the world.

‘A world without global leadership may last for a decade or more,’ Yan told me. ‘The competition between China and the US prevents the collective leadership of major powers. Therefore, although there is a vacuum for global leadership, no country seems ready to fulfil it in the near future. Henry Kissinger said that the pandemic will alter the world. Nevertheless, I would argue that it only strengthens the existing international political trends rather than change them.”

This has created its own stresses that aren’t often easy to see from the outside. On the economic front, the Party has

to steer a slowing economy that is diluting what has been one of its key India’s China Challenge 387 sources of legitimacy. China has made huge strides in creating an innovation economy, but the next steps are getting ever harder, particularly as it confronts an increasingly difficult external environment.

Globally, the pushback against China has been growing. The country’s global aspirations depend as much on its own ambitions as they do on how the rest of the world, including India, chooses to accommodate them, and most importantly, whether a credible alternative emerges for countries that are drifting deeper into China’s orbit.

If it’s foolhardy to predict China’s future, one thing that 2020 has reminded us, perhaps not in the most ideal way,

is how the country impacts our lives. It shouldn’t have to take crises to tell us that, but alas, we in India don’t otherwise seem to pay enough close attention to our biggest neighbour, whose political, economic and social transformations will continue to affect our lives, in ways we might not always realise, Krishnan concludes. (IANS)