By Aparajita Gupta

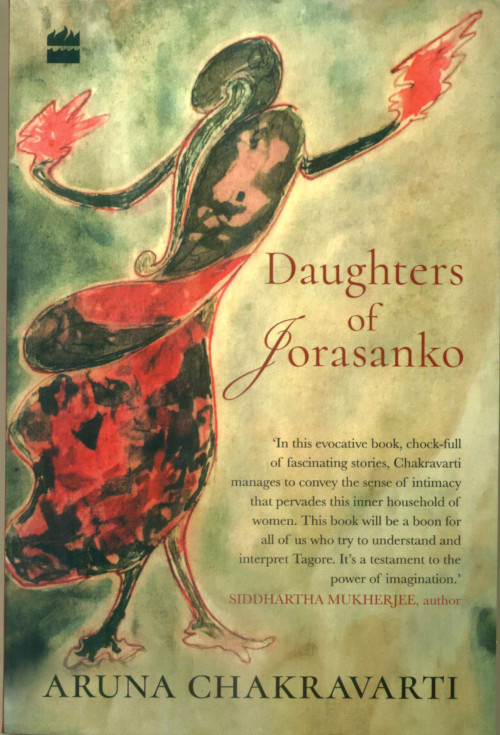

(Title: Daughters of Jorasanko; Author: Aruna Chakravarti; Publisher: HarperCollins India; Pages: 327; Price: Rs 399)

Based on the life of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore and his extended family and friends, this semi-fictional book tries to capture several vignettes of Bengali society and its culture of that era. By doing so, it also gives us an insight into the larger canvas that was India.

Jorasanko, a neighbourhood north of Kolkata, has been linked to Tagore’s name forever. The book tells, with great aplomb, the story of Digambari, Prince Dwarkanath’s wife, who banished her illustrious husband from her household because he went against the “dharma” of his Vaishnav ancestors by hosting receptions where meat and liquor were served.

This uncompromising act of Rabindranath’s grandmother showed the existence of women of substance in a household that can be termed as Bengal’s first family. One is tempted to raise at least half a toast to this act of early rebellion, even though it was against the freewheeling lifestyle of a man who also hobnobbed extensively with Europeans.

This uncompromising act of Rabindranath’s grandmother showed the existence of women of substance in a household that can be termed as Bengal’s first family. One is tempted to raise at least half a toast to this act of early rebellion, even though it was against the freewheeling lifestyle of a man who also hobnobbed extensively with Europeans.

As painted by the author Aruna Chakravarti, the novel is largely set between the years 1859 and 1902 when a feudal mindset was slowly, reluctantly giving way to a liberal, westernised one.

At the hub of the transition was Jnanadanandini, the dynamo wife of Maharshi Debendranath’s second son Satyendranath Tagore. Jnanadanandini has been dignified with the title of the “first modern woman” of Bengal when modernism was still in its infancy. She was perhaps one of the strongest influences on Rabindranath, who would eventually go on to change the face of Bengali literature forever.

Providing a deeper insight into Tagore’s life, the author shows how Rabindranath flourished under the influence of Jnanadanandini, though it was his other sister-in-law, Kadambari, who discovered his potential as a poet and helped him to free the muses trapped within.

Chakravarti, an academic, creative writer and translator, took the milieu in which the poet-philospher lived, anchoring her vivid imagination to what would have been, rather than what really was.

The book explores Rabindranath Tagore’s engagement with the freedom movement and his vision for holistic education, bringing alive his latter-day inspirations, Ranu Adhikari and Victoria Ocampo, mapping the histories of Tagore’s women, even as it goes on to describe the twilight years of one of the greatest luminaries of modern times.

Rabindranath’s wife Mrinalini was unfortunate in the way she has been viewed by his contemporaries and succeeding generations of his readers as an “unworthy spouse” of one of the greatest men of the land.

But in the author’s eyes she was not an unworthy spouse if one takes into consideration the restrictions under which women of the time were placed. Which should mean that the women who rose above their calling in the household did it despite those extreme odds.

The book also delves deeply into the disquiet in the poet’s heart, his sadness and melancholy. How unhappy he was when he found that his ailing daughter was not getting adequate care from her in-laws.

Amidst the many unhappinesses, the bard was also busy building his dream project at Santiniketan — Visva-Bharati — which would become one of the finest universities of the land.

The book is a sequel to the author’s Jorasanko, published in 2013. Both are part-fictional accounts of life and times of Tagore and the many women who influenced him in the ancestral mansion.

The background themes of this rich palette include the Bengal Renaissance, the socio-political scene of India, the British colonial rule and the proposal by Lord Curzon to divide the poet’s beloved land into two.

The fiction merges so well with the colours of history that you cannot help but let your senses ride along, in a journey which is both rich and satisfying. Read the book in one sitting if you can — the age comes alive and grabs you for a lasting impact.