BY VIKAS DATTA

Love – desired, fulfilled, sublimated, subverted, or thwarted – is the bedrock of Hindi film songs but scarcely anything can beat the expressively bold, yet, elegantly simple landmark song from “Mughal-e-Azam”.

Especially when the radiant – and bewitchingly defiant – Anarkali, having already goaded the mighty monarch with her declaration of fearless love, goes on to ask: “Parda nahi jab koi Khuda se, bandon se parda karna kya?”

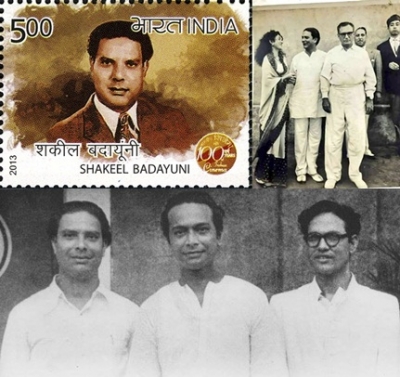

Surprisingly enough, the lines came from the unassuming, independent-minded Shakeel Badayuni, who was no dyed-in-the-wool radical revolutionary like most of his contemporaries (Sahir Ludhianvi for one), but for all that, considered matchless in portraying all phases of the human condition besides celebrating India’s diversity.

What would Hindi classics like “Mughal-e-Azam”, “Mother India”, “Aan”, “Chaudhvin ka Chand”, “Sahib, Bibi Aur Ghulam”, “Baiju Bawra”, “Bees Saal Baad”, “Ganga Jamuna” and others without their songs? Set to captivating music by a range of maestros and rendered with gusto and verve by a gamut of talented singers, they are also remembered for their memorable words — all courtesy Shakeel Ahmed ‘Shakeel Badayuni’, whose 107th birth anniversary falls on Wednesday (August 3).

One of the gifted, already famous poets the Hindustani film industry could attract, Shakeel also demonstrated that the skill of poetry can be intrinsic, not inherited, for none of his close relatives was a poet.

Born in Badaun on August 3, 1916 in a cleric’s family, he quickly discovered his inclination. By the time he joined the Aligarh Muslim University in 1936, he was already an accomplished poet, much in demand in mushairas for both the quality of his verse and its presentation, being particularly skilled in reciting in “tarranum” (rhythmic cadence) — which may explain his penchant for song-writing.

However, unlike many others of his generation, Shakeel was not part of the leftist “Taraqqi Pasand” (Progressive) movement, preferring to write only about romance and the human condition.

As he declared: “Main Shakeel dil ka hoon tarjuman/Ke mohabbaton ka hoon raazdaan/Mujhe fakhr hai meri shayari/Meri zindagi se juda nahin.”

After graduating, he held a government job for a few years, before resigning in 1944 and heading to Bombay to work in the film industry. A fortuitous meeting with music composer Naushad, who had just gained a measure of success, laid the foundation for an enduring partnership.

With Mohammad Rafi, they became a trio which is behind some of the most memorable Hindi film songs, spanning the entire range of emotions — be it the gentle anguish of “Suhani raat dhal chuki hain” (“Dulari”, 1949), the fatalistic “Yeh zindagi ke mele” (“Mela”, 1948), the gently-pessimistic “Koi sagar dil ko behlata nahi” and the deeply-pessimistic “Guzre hain aaj ishq mein ham us maqaam se” (“Dil Diya Dard Liya”, 1966), the devil-may-carish “Dil mein chhupa kar pyaar ka toofan” (“Aan”, 1952), the playful “Hami se mohabbat hami se laadai” (“Leader”, 1964), the imploring “Mere mehboob tujhe meri mohabbat ki kasam” (“Mere Mehboob”, 1963), and many more.

Though Shakeel is most known for his work with Naushad, he also crafted magic with music directors like Ravi with “Chaudvin ka chand ho”, from the eponymous film, being one of the intensely romantic songs ever seen, and displaying Urdu poetry’s tradition of ‘sarapa’ where the beloved’s beauty is described and compared to nature — “Zulfen hain jaise kandhe pe baadal jhuke hue/Aankhen hain jaise mai ke pyaale bhare hue…” And then, the zenana-based tongue-in-cheek “Sharmaa ke ye kyon sab pardanashin” from the same film is another delight.

He also worked with Hemant Kumar for “Bees Saal Baad”. And while the melodious “Beqarar kar ke hamen yun na jaaiye” and the eerily haunting “Kahin deep jale kahi dil” showcase his virtuosity, the high mark is the playful “Zara nazron se kehdo ji…”, sung by Hemant himself, with its simple yet evocative romantic remonstrances delivered conversation-style: “Qatil tumhe pukaroon ke jaan-e-wafa kahun/Hairat mein parh gaya hoon ke main tum ko kya kahun”.

But what sets Shakeel apart is his syncretism.

“Mughal-e-Azam”, which was a high point for him as well as Naushad, has not only the hamd “Bekas pe karam kijiye, ae Sarkar-e-Madina”, but also the Hindu folkloric “Mohe panghat pe nandlal…” And, there is “Jai Raghunandan Jai Siyaram” (“Gharana”, 1961), which was rumoured to be part of this film, but went on to figure in another film.

While there is the often quoted example of “Man Tarpat hai hari darshan ko” (“Baiju Bawra”, 1952 – the best example of transcendent ability of the Naushad-Shakeel-Rafi troika), there was also: “Madhuban mein Radhika naache re…” (“Kohinoor”, 1960), “Mohan ki muraliyaa baaje…” (“Mela”), “Jamuna ke paar koi bansi bajaaye” (“Sitaara”, 1955), “Insaaf ka mandir hai ye Bhagvan ka ghar hai” (“Amar”, 1954), “Holi aayi re kanhai, Holi aayi re” (“Mother India”, 1954) and many others, where Shakeel proved himself adept at depicting the imagery and ethos of Hinduism.

And while one of the foremost Urdu poets, he could also very capably prove himself in the vernacular of the heartland as well as Shailendra Singh. While “Nain lad jaiyen to manva ma kasak hoiba kari” from “Ganga Jamuna” (1961) is the obvious example, there were also “Dagabaaj tori batiyan”, “Ho re ho jhanan ghunghar baaje…”, and “O chaliya re man mein hamaar najar…” from the same film.

And Shakeel was not always serious — we also owe to him that quintessential Hindi film Happy Birthday song: “Ham bhi agar bache hote…” (“Door Ki Awaaz”, 1964)

His involvement with films meant less time for his own poetry, but he never gave it up, with four volumes of ghazals (including many immortalised by Begum Akhtar like “Ae Mohabbat tere anjaam pe rona aaya” and “Mere hamnafas, mere hamnawaa”), and two of his film verse.

A winner of the Filmfare Award for lyricist three years in a row (1961 for “Chaudvin Ka Chand”, 1962 for “Gharana” and 1963 for “Bees Saal Bad”), he died at the height of his prowess in 1970, following diabetes-related complications – and was thankfully spared the indignity of becoming redundant like his film mentor, Naushad. (IANS)