By Jayanti Bandyopadhyay and Yogita Miharia

BELMONT, MA– Stage Ensemble Theatre Unit, known as SETU, recently completed four sell-out shows in April at the Mosesian Center for the Arts with the first English adaptation play of one of the most popular novels in India, Devdas. (Picture Credits: Thomas Arul, Ganesh Devuluri, Maria Fonseca, Fotu Duniya, Yogita Miharia.)

The next four shows are from May 17 to May 19 at the same venue (www.setu.us). The novelist, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, never imagined that this romantic tragedy would become his most adapted novel for films in many languages in India.

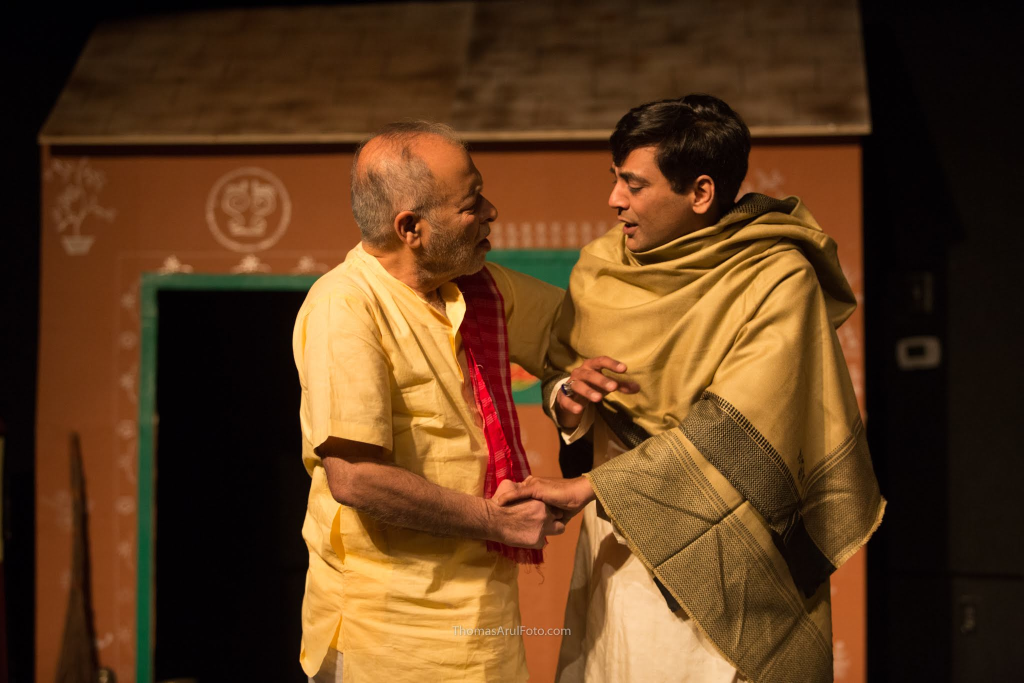

Now, SETU, has brought Devdas to an international audience in New England with Subrata Das’ English adaptation of the script and direction. Devdas, a period piece from 100 years ago situated in Bengal in India, depicted the unique social hierarchy of the region through story telling. A key component to project this life style on stage is to integrally relate the characters of the play through costume. Thus, designing appropriate costumes is at the core of this production.

Now, SETU, has brought Devdas to an international audience in New England with Subrata Das’ English adaptation of the script and direction. Devdas, a period piece from 100 years ago situated in Bengal in India, depicted the unique social hierarchy of the region through story telling. A key component to project this life style on stage is to integrally relate the characters of the play through costume. Thus, designing appropriate costumes is at the core of this production.

From the embryo formation phase of presenting Devdas, Jayanti Bandyopadhyay understood that for costume to be an embedded part of this play, at least three themes must be present: 1) the authenticity of the costume depicting the era along with make-up and stage design, 2) a buy-in of costume by the actors, 3) and a meeting of the minds between the director and the costume designer/director. The audience would need to feel like a fly on the wall as the actors would appear to have come alive from the pages of the play.

From the embryo formation phase of presenting Devdas, Jayanti Bandyopadhyay understood that for costume to be an embedded part of this play, at least three themes must be present: 1) the authenticity of the costume depicting the era along with make-up and stage design, 2) a buy-in of costume by the actors, 3) and a meeting of the minds between the director and the costume designer/director. The audience would need to feel like a fly on the wall as the actors would appear to have come alive from the pages of the play.

Authenticity: As they were brought up in Bengal, both Jayanti and Subrata had access to primary data regarding what men and women wore in villages even 100 years ago. They grew up watching their parents and grandparents wearing the dhotis, kurtas and saris wrapped the typical aatpoure (ordinary) way made with simple cotton fabric of several varieties even in the later-half of the twentieth century. The adapted play emphasized the stark contrast between the aristocrats and the commoners.

Authenticity: As they were brought up in Bengal, both Jayanti and Subrata had access to primary data regarding what men and women wore in villages even 100 years ago. They grew up watching their parents and grandparents wearing the dhotis, kurtas and saris wrapped the typical aatpoure (ordinary) way made with simple cotton fabric of several varieties even in the later-half of the twentieth century. The adapted play emphasized the stark contrast between the aristocrats and the commoners.

The babus (aristocrats) wore dhutis made with fine muslin-type cotton fabric with ornate borders with fine pleats flowing all the way to their ankles. The commoners wore plainer ones, much higher between their knees and ankles for ease of movement in doing hard labor. Babus wore fine full-sleeve kurtas mostly white in color while servants would wear half kurtas referred to as fotuas made with coarse fabric in various colors. The aristocrats would wrap around a scarf made of fine cotton or silk (uttariyas) when going out and commoners would most likely have a gamchha (a checkered coarse cotton towel) on their shoulder or around their head. When Babus visited kothas or prostitutes’ houses, they would wear their fine clothes with jasmine flower garlands wrapped around their wrists to lighten their moods.

The babus (aristocrats) wore dhutis made with fine muslin-type cotton fabric with ornate borders with fine pleats flowing all the way to their ankles. The commoners wore plainer ones, much higher between their knees and ankles for ease of movement in doing hard labor. Babus wore fine full-sleeve kurtas mostly white in color while servants would wear half kurtas referred to as fotuas made with coarse fabric in various colors. The aristocrats would wrap around a scarf made of fine cotton or silk (uttariyas) when going out and commoners would most likely have a gamchha (a checkered coarse cotton towel) on their shoulder or around their head. When Babus visited kothas or prostitutes’ houses, they would wear their fine clothes with jasmine flower garlands wrapped around their wrists to lighten their moods.

Similarly, among women, the status difference had to be apparent on stage. While equipped with ample primary research data, exploring into the reason for the aatpoure style of wearing the sari revealed interesting facts. This style calls for wrapping the sari in an anti-clockwise fashion without pleats that leaves no exposed area of the body. The modern universal way of wrapping the six-yard material gives much opportunity to show the waist and the back.

Similarly, among women, the status difference had to be apparent on stage. While equipped with ample primary research data, exploring into the reason for the aatpoure style of wearing the sari revealed interesting facts. This style calls for wrapping the sari in an anti-clockwise fashion without pleats that leaves no exposed area of the body. The modern universal way of wrapping the six-yard material gives much opportunity to show the waist and the back.

Women in villages of Bengal did not wear blouses or petticoats as they did not step outside the house reflecting a typical patriarchal society. The women from enlightened families such as the Tagores (Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore’s family) introduced the blouse and the petticoat and the modern wrapping style as they began to step out of the house (saris in wikipedia.org) – an intriguing fact indeed regarding an evolutionary step toward women’s emancipation.

Women in villages of Bengal did not wear blouses or petticoats as they did not step outside the house reflecting a typical patriarchal society. The women from enlightened families such as the Tagores (Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore’s family) introduced the blouse and the petticoat and the modern wrapping style as they began to step out of the house (saris in wikipedia.org) – an intriguing fact indeed regarding an evolutionary step toward women’s emancipation.

Continuing with the status difference, Devdas’ mother Harimoti as an aristocrat landlord’s wife, would wear richer saris with wider red borders and a lot of gold jewelry as opposed to Parvati’s mother from a much lower status wearing a simpler cotton sari and just a simple gold chain. Parvati’s widowed grandmother, as all widows of all ages, must wear an all-white sari with no jewelry other than a tulsi-beaded necklace depicting spirituality and no make-up. However, when Harimoti becomes a widow, her sari could be, albeit white or cream, of finer quality with silk fabric. Married women would have their hair parted in the middle with sindur and wear red and white bangles termed as shakha and pola.

Continuing with the status difference, Devdas’ mother Harimoti as an aristocrat landlord’s wife, would wear richer saris with wider red borders and a lot of gold jewelry as opposed to Parvati’s mother from a much lower status wearing a simpler cotton sari and just a simple gold chain. Parvati’s widowed grandmother, as all widows of all ages, must wear an all-white sari with no jewelry other than a tulsi-beaded necklace depicting spirituality and no make-up. However, when Harimoti becomes a widow, her sari could be, albeit white or cream, of finer quality with silk fabric. Married women would have their hair parted in the middle with sindur and wear red and white bangles termed as shakha and pola.

The courtesans needed attention in designing their mujra-style outfits and jewelry with help from the lead choreographer, Vasudha Kudrimoti.

The courtesans needed attention in designing their mujra-style outfits and jewelry with help from the lead choreographer, Vasudha Kudrimoti.

The children, studying in a village school set outdoors in a hot climate, would typically wear light clothing as in boys with dhotis with bare chests and girls with simple cotton saris without blouses. A compromise had to be made in letting the boys wear white undershirts on stage per their request. Wearing a simple saffron cotton sari as a Baul girl, Sachi Badola enthralled the audience with her rendition of a Baul song in Bengali with her beautiful trained voice.

The costumes had to be brought directly from Kolkata from those small shops still carrying the appropriate clothing and imitation gold jewelry from the era. Jayanti benefitted from consulting with her friends in Kolkata, particularly Banani and Sovanlal Dasgupta, Saswati Chowdhury, and Nandita Guha Thakurta. Many of her friends in New England happily shared the treasures hidden in their own closets. The whole process became as though planning for one’s own daughter’s wedding.

The costumes had to be brought directly from Kolkata from those small shops still carrying the appropriate clothing and imitation gold jewelry from the era. Jayanti benefitted from consulting with her friends in Kolkata, particularly Banani and Sovanlal Dasgupta, Saswati Chowdhury, and Nandita Guha Thakurta. Many of her friends in New England happily shared the treasures hidden in their own closets. The whole process became as though planning for one’s own daughter’s wedding.

The buy-in: Yogita Miharia, an actor, described how she and other actors evolved from the experience. In the beginning, the entire cast was excited as well as nervous and hesitant about the unfamiliar way of wearing Bengali style sarees or dhotis. As they practiced and perfected, that feeling of fear changed to a sense of empowerment as the costumes and direction not only helped them get ready for stage but helped them get into the character. With all of them having no real knowledge of that era and very few being familiar with the Bengali culture, the costumes were a vehicle to transport them into that place. With a mix of poor and rich characters in the story, the clothes were the most effective way to show to the audience how unbalanced the social structure was; rich people wearing jewelry and finery whereas the poorest ones such as the Baul women not even a blouse under their sarees. Some were reminded of their grandparents whereas some remembered their own wedding.

The buy-in: Yogita Miharia, an actor, described how she and other actors evolved from the experience. In the beginning, the entire cast was excited as well as nervous and hesitant about the unfamiliar way of wearing Bengali style sarees or dhotis. As they practiced and perfected, that feeling of fear changed to a sense of empowerment as the costumes and direction not only helped them get ready for stage but helped them get into the character. With all of them having no real knowledge of that era and very few being familiar with the Bengali culture, the costumes were a vehicle to transport them into that place. With a mix of poor and rich characters in the story, the clothes were the most effective way to show to the audience how unbalanced the social structure was; rich people wearing jewelry and finery whereas the poorest ones such as the Baul women not even a blouse under their sarees. Some were reminded of their grandparents whereas some remembered their own wedding.

Details like the “topor and mukut” and ululating for the wedding were the much-needed authentic touches that made the wedding scene so real, noted one actor. Every costume molded the body language of the actors naturally to help them fit in the role. For the child actors, this was the most unique experience as all of them had never worn a saree or dhoti. The young girls said that the saree made them truly feel like a village belle from 100 years ago.

Details like the “topor and mukut” and ululating for the wedding were the much-needed authentic touches that made the wedding scene so real, noted one actor. Every costume molded the body language of the actors naturally to help them fit in the role. For the child actors, this was the most unique experience as all of them had never worn a saree or dhoti. The young girls said that the saree made them truly feel like a village belle from 100 years ago.

All the female actors enjoyed indulging in Bengali sarees, silks and jewelry. All actors, male and female, agreed that the costumes, the movements, and enjoying the lost ‘floor’ culture were the true essence of the play! All actors empathized how the characters ate sitting, talking, and studying on the floor.

Meeting of the minds: One example of how the director’s vision coincided with the costume and make-up directors’, the lead choreographer’s, the stage designer’s and the light and sound team’s visions was in enacting the wedding scene on stage. While dancers wearing bright colored-cotton saris entertained with a haldi dance and the wedding was happening on stage, the grandmother in stark white stood prominently lit in one corner crying as she was not allowed to participate. SETU experimenting with alternative theater had actors playing multiple roles in the same show. The make-up director, Susmita Ghosh, had to work her magic in transforming an actor portraying an aristocrat landlord into a bullock-cart driver in ten minutes.

Audience members expressed appreciation of the costumes: one of them said that every outfit seemed very customized to the role, another said that the costumes enhanced the emotions being portrayed by the actors. A simple white saree effectively conveyed the sadness in the mourning scene. Another theater enthusiast said that the costumes and sets transported her to Bengal in the early 1900s. Yet another viewer said that it was not just about the costumes, it was about the cohesion between the costumes and make-up, the stage (built with all organic materials), and the direction – a definition of a good production team indeed.

For those who have not yet seen the play, we hope to have aroused their interest in experiencing the early 1900s in Bengal through SETU’s Devdas production on May 17 (7 pm), May 18 (2 pm and 6 pm) and May 19 (2 pm) – tickets at www.setu.us.

(Picture Credits: Thomas Arul, Ganesh Devuluri, Maria Fonseca, Fotu Duniya, Yogita Miharia.)