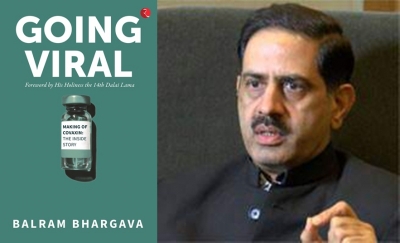

New Delhi– “We pulled off an extraordinary feat. After the tension, the drama, the hard work, the long nights, the constant fear of illness and death, the brainstorming, the travel, the testing the fatigue, the adrenalin rush… After all this, lets pause and marvel. There is much to marvel at,” writes Balram Bhargava, the Director General of the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR), in “Going Viral” of the race against time to develop the Covaxin vaccine against Covid-19.

With the SARS-CoV-2 virus finally isolated, cultured and better understood in March 2020 – with India only one of five countries to do so – “we at ICMR started thinking seriously about developing a vaccine of our own. The global and national situations were dire, it was clearly time for bold action”, Bhargava, who is also a professor of cardiology at AIIMS, writes in the book, subtitled “Making of Covaxin: The Inside Story” and published by Rupa.

“Apart from hard science, vaccine development also requires manufacturing power and a whole lot of logistical manoeuvring. The average time from discovery to production for any vaccine in the past was 10 years. We were on the lookout for industrial partners with whom we could collaborate for a vaccine. The first company to approach us was Bharat Biotech… The proposal was an exciting one as it fitted well with the Indian government’s publicly stated prioritization of indigenous technology, production and capabilities in all sectors,” Bhargava writes.

“We wanted Bharat Biotech to work on an inactivated vaccine. It turned out to be the perfect choice,” he adds.

Inactivated vaccines, Bhargava explains, are developed by ‘killing’ the lab-grown, well-characterised virus by using chemicals and subsequently generating a product with a known concentration of inactivated viral particles. These destroy the pathogen’s ability to replicate but keep it ‘intact’ so that our immune system can still recognise it and produce an immune response. These inactivated viruses are then reproduced in large quantities and prepared for use as a vaccine.

Once the BBIL (Bharat Biotech International Limited)-ICMR-NIV (National Institute of Virology) team had developed three inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates – BBV152A, BBV152B and BBV152C – it tested them on small animals like mice and rabbits.

“The goal was to see if the test animals produced neutralising anti-bodies that provided any protection when subsequently challenged with the live virus…Out of the three candidates, BBV152A was the winner,” Bhargava writes.

“Strict quality control ensured that nothing went wrong at any point of time. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 ELISA test kits developed by ICMR-NIV were used for preclinical studies that required detecting antibodies generated following vaccination.

“From ICMR headquarters, we kept a regular watch on the entire process. We monitored the work and sprang into action to expedite the necessary approvals and ensure supplies of critical equipment and materials, including reagents,” he adds.

Then came some Serious Monkey Business, as Bhargava subtitles the chapter titled An Indian Vaccine From Dream To Roll-Out: India does not have any laboratory-bred Rhesus macaques and a countrywide search of zoos and institutes failed to locate any. Eventually, 20 Rhesus macaques were located deep in a forest near Nagpur.

They were divided into four groups of five each. One group was administered a placebo which did not have any active substance meant to affect their health while three groups were immunised with the three different BBV152 vaccine candidates at 0 and 14 days. All the macaques were exposed to SARS-CoV-2 14 days after the second dose, the virus being delivered deep into the lungs via a bronchoscope.

“The macaques had strong immune responses to the vaccine. They were protected when they were exposed to the virus. The vaccinated primates cleared the virus well from their lungs, nasal and throat passages within seven days of being infected. Daily bronchoscopy with lavage was taken from deep in the lungs.

“The vaccinated groups, unlike subjects in the placebo group, did not develop pneumonia. Overall, the vaccines showed remarkable immunogenicity and protective efficacy. It was a turning point for all of us at ICMR and Bharat Biotech. It was one of the best results we had encountered. The vaccinated monkeys showed excellent anti-body response with no adverse effect. We thereafter concluded that the vaccine was both safe and effective and that with the new adjuvant it could be administered in the dose of either three or six micrograms.

“We finally had a completely indigenous vaccine, an epitome of Atmanirbhar Bharat,” Bhargava writes.

Thereafter, the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) granted Covaxin Emergency Use Authorisation (EUA) on January 2, 2021 after two phases of human clinical trials even as the third phase was underway.

“There were critics who said we had to complete Phase III before giving the vaccine to humans before it can be given to the nation. But there is a Gazette notification of 19 March 2019, which is pre-COVID, and it said that in national interest, if a product has successfully undergone the Phase II trial, it can be deployed. In other words, emergency authorisation can be given. And that rule was invoked by the Drugs Controller” when approval for Covaxin was issued,” Bhargava writes.

India’s mass vaccination drive began on January 16, 2021.

Bhargava also laments that “as we battled one challenge after another and found ways to deal with them, and firmed our resolve to have an Indian vaccine, a tiny section of our population, the so-called experts in the media and elsewhere, began to raise doubts on our ability. It was not the first time that an Indian initiative was being ridiculed even before it had the opportunity to succeed. But it was disgraceful that it should happen at a time when our scientists and researchers were showing a steely determination find a solution to the pandemic” and ascribes this to “the Macaulay-mindset at work”.

“Today, I am filled with a sense of urgency to vaccinate India and prevent a repeat of the tragic second wave. We have to be very careful.

“Ironically, the best way forward for us is to imitate our enemy: we need to mutate and evolve in order to outsmart the virus. And that is what we are doing. When it attacks, we defend. When it hides, we find it. When it changes course, we are right there behind it. When we need to, we call in reinforcements.

“At this moment, as the world waits to see the pandemic in the rear-view mirror, the superheroes of the day are scientists: women and men who stay smarter than the virus, who change and adapt and innovate so we can all have a better shot at a better tomorrow,” Bhargava concludes. (IANS)