By Vikas Datta

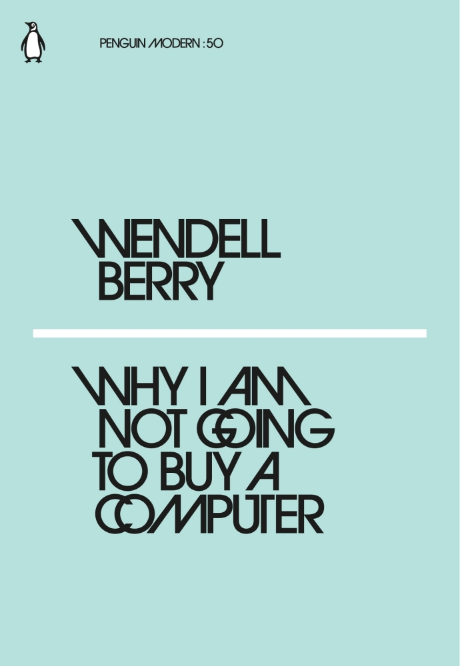

Title: Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer; Author: Wendell Berry; Publisher: Penguin Classics; Pages: 64; Price: Rs 50

In this era of high technology, expressing disinclination to use a computer would be tantamount to declaring yourself a fossil. But have the ubiquitous computers — or rather the technological progress they embody — been an unqualified boon for us?

There may be no simple answer; and in any case, it would differ on a generational basis — from those who have practically grown up with computers, and their elders, who can still recall a world where they were not that common.

There may be no simple answer; and in any case, it would differ on a generational basis — from those who have practically grown up with computers, and their elders, who can still recall a world where they were not that common.

But there are some — among both sections — well aware that the growing presence of computers in every field of human activity also raises a few concerns. Artificial intelligence (AI) and its consequences is one, but slowly but steadily diminishing human ingenuity, knowledge and endeavour — and even thinking — is a rather bigger, though lesser-known, problem. Take anyone who turns to Google to find a fact, or a spelling — to find, not to cross-check (William Poundstone’s “Head in the Cloud”, 2016, is a worrying read in this regard).

However, it was nearly three decades ago that American novelist, poet, environmental activist, cultural critic and farmer Wendell Berry invoked these concerns while setting out his reasons for not investing in a computer to help him in his writing. As this book, reproducing his 1987 piece for “Harper’s Weekly”, shows, some of his points are still valid even now. While dealing with the US of the late 1980s, some will also strike a chord across time and space.

Stressing he did not “admire” his reliance on energy corporations and wanted to be “hooked” on them as less as possible, Berry holds this is the primary reason for not acceding to the demand of several people that he get a computer.

Asserting he “did not admire the computer manufacturers a great deal more than I admire the energy industries”, he says he was familiar with the former’s “propaganda campaigns that have put computers into public schools in need of books”.

Berry also argues that the stand that computers are “expected to become as common as TV sets in ‘the future’ does not impress or matter to me” for he does not see them advancing, even a bit, anything that matters — peace, economic justice, ecological health and so on.

He goes on to list his nine standards for useful technological innovation. However, all this barely covers two (A4) pages — but then there are a selection of letters, mainly critical, his article evoked, especially his quips about his wife’s role in his writings, and his joint rejoinder to them, questioning “technological fundamentalism”.

But what occupies most of this book, among Penguin’s special printing selection from 50 classics, is a longer essay titled “Feminism, the Body and the Machine”.

In this, Berry, expanding on his previous arguments, gives an eloquent and reasoned, yet provocative, pitch on how technological progress, or even the modern economic system that props it up, may not always be very positive, since it may be dehumanising us.

This, he polemically but cogently argues, has made the modern household “the place where the consumptive couple do their consuming” and “nothing productive” — well almost nothing — is done. How the aims of gender equality cannot be served by women submitting to “the same specialisation, degradation, trivialisation and tyrannisation of work” that men have, and the fact that work can be a gift too is overlooked.

Berry also deals with the shortcomings of modern education where “after several generations of ‘technological progress’… we have become a people who cannot think about anything important” and goes on to question the very purpose of all this progress, which is not having a too salutary effect on our lives — family or personal — despite its promise of “money and ease”.

There is much more which merits a careful consideration, though many of us will dismiss this as an obscurantist rant. But as Berry, now over 83, says: “My wish simply is to live my life as fully as I can.”

Do we need devices for this? (IANS)